In the aftermath of the Monsanto Tribunal (The Hague, 14-16 October 2016) Cris Panerio reflects on the impact of Monsanto in the Philippines and on alternative and more respectful ways of doing agriculture.

“Monsanto Guilty!” This was the resounding declaration of more than 100 farmers and activists who gathered in a forum supporting the Monsanto Tribunal. The International Tribunal is focused on the so-called ‘crimes against humanity’ of the Monsanto Corporation, one of the world’s biggest transnational corporations (TNC) dealing with agricultural chemicals and seeds used in many third-world countries such as the Philippines. In MASIPAG, a farmer-led network of people’s organizations, NGOs and scientists based in the Philippines, there are many concerns in relation to Monsanto’s influence and actions, as Filipino farmers have been using Monsanto’s technologies and products such as the ill-fated Bt-corn for more than ten years, and other recent genetically modified crops and chemical inputs such as the Roundup herbicide, with already tangible consequences.

Historically, Monsanto has always been a threat to farmers’ lives and the environment, and it has been known to develop ‘toxic chemicals,’ some of which have already been banned in Europe such as Lasso, as well as the chemical component of Agent Orange, a potent herbicide used by the US Army during the Vietnam War. The effects of Agent Orange, used as a weapon to defoliate the thick jungle cover in Vietnam, continue to affect Vietnamese generations with cases of birth defects and disfigurement. Even US military veterans and their descendants suffered from the effects of Agent Orange, leading to a class action lawsuit against Monsanto and other manufacturers of chemical products in 1984. “Now Monsanto is ruling over the food and agriculture system, with their chemical inputs and genetically modified seeds, driving farmers deeper into poverty and hunger.” said Virginia Nazareno, a farmer-leader from Gen. Nakar, Quezon.

Monsanto’s GM Crops

Monsanto has gained growing notoriety in the Philippines with the introduction of genetically modified corn in the 2000s. The Bt corn was commercialized in 2002 promising farmers with hefty incomes and yields as the GM corn was supposed to be pest resistant thereby reducing the use of chemical pesticides. More than 10 years later however, farmers remain poor as the GM corn failed to deliver its promise, and led them instead to chronic indebtedness, hunger and poverty.

What is shocking is that what was often sold as a way to increase income, has actually brought about more poverty and economic instability. In a study done by MASIPAG in 2012 on the socio-economic impacts of GM corn among poor farmers, results showed that the expensive cost of GM corn production has driven farmers to local usurers and traders, incurring as much as 40% interest per cropping season that they are unable to pay off. The use of GM corn seeds entail the use of synthetic chemicals, and together they make up 40‐48% of the total expenses that a farmer spends per season, and all of these go to the corn traders/financiers and agrochemical companies. Unfortunately, yields of GM corn are inconsistent, with most farmers losing as much as 10,000 pesos (more than 180 Euros) after a bad harvest. “These poor farmers are sure markets of Monsanto, who owns and develops the seeds and the chemical inputs,” said Robert Solomon, a farmer from Antique. “It is no wonder that Monsanto will use any means, including the collusion with the local capitalists, just to make sure they continue to profit off the suffering of the farmers.”

Guilty of Corporate Greed

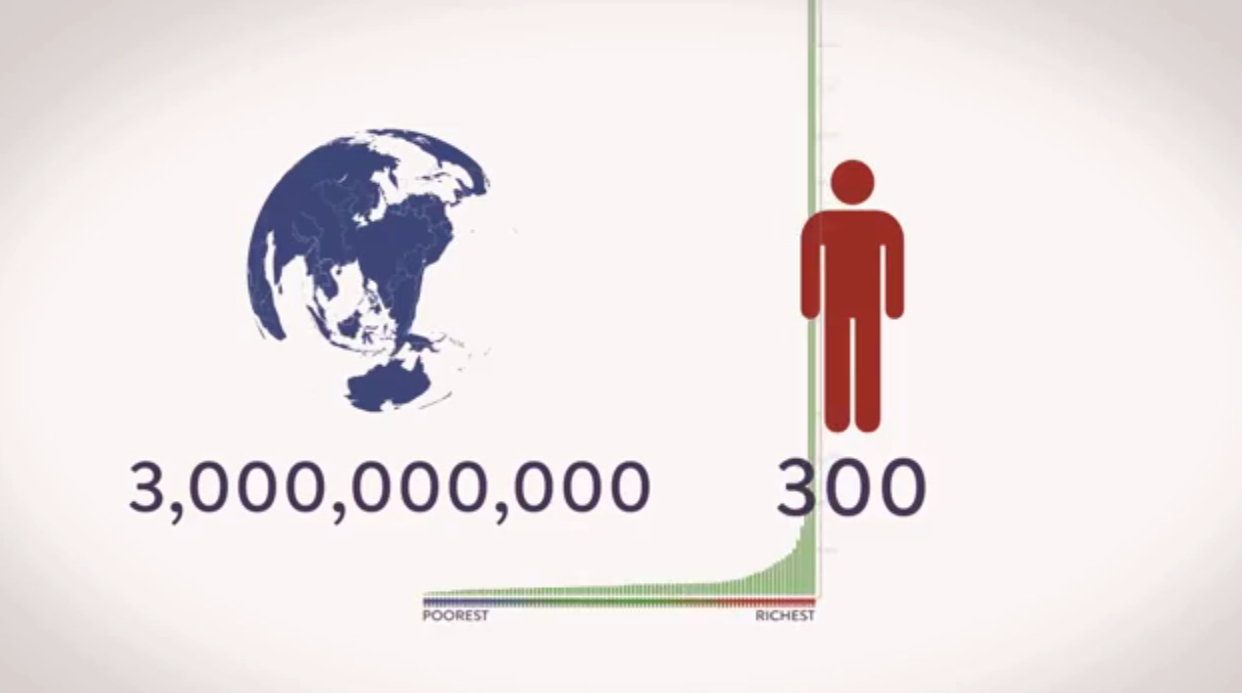

Monsanto is the perfect symbol of corporate greed, where monopoly and control is centered among the few powerful corporations that thread on the interest of the poor farmers. With the imminent merging of Monsanto with Bayer, another giant corporation, their hold over the food and agricultural system is expected to worsen. With the recent merging of Syngenta and ChemChina, and the planned merger of Dow and DuPont, the world’s seed and agrochemical market will be at the mercy and control of three big entities. Critics also expect more aggressive land grabbing practices by these companies and their local cohorts where massive agricultural lands will be converted to GM plantations.

“We will continue to lose our control over our local seeds, which are being edged out by the GM seeds, and we may even lose our lands,” said Ms. Nazareno. “Farmers will continue to be tied with this exploitative system where the only winner is Monsanto.” That is why we are in solidarity with the International Tribunal which believes that Monsanto has committed crimes against humanity and the environment.

From October 14-16, civil society organizations at the International Tribunal against Monsanto assessed the allegations made against Monsanto, and evaluated the damages caused by this transnational company. Using the “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights” and the Rome Statute, the tribunal examined Monsanto’s potential criminal liability with the crime of ecocide.

Farmers from all over the Philippines, as well as other supporters and advocates in other countries are expressing their solidarity with the call against Monsanto. Gathering farmers together in such protests is crucial, as Monsanto is guilty of damaging the environment and harming farmers’ lives. We can win against Monsanto if we are united with our efforts not only in the Philippines, but globally, with the use of local seeds, environmentally-sound farming systems, and thriving community markets.

MASIPAG as a way of resistance

In the Philippines, farmers have been resisting and fighting back against corporations such as Monsanto. By using improved local varieties and developing their own rice, MASIPAG farmers have severed their dependence and reliance on seed companies that commercializes living, genetic resources. Their local innovations in managing crop pests and diseases have been proven effective enough that they do not need to patronize synthetic pesticides and herbicides which threaten human and environmental health. This is a model that works and that has been presented in various international fora such as the workshop recently organized by the CIDSE network “Climate and Agriculture: Harvesting People’s Solutions for Sustainable Food Systems”. In the workshop, many others people’s solutions coming from the grassroots show that real solutions for the food and climate crisis have to come from the bottom.

Seeds in the hands of farmers—and their knowledge to breed and improve varieties—are forms of regaining the seeds and the farmers’ antidote to the lock-ins of intellectual property on seeds, the patenting of life forms and the free and subsidized distribution of input-dependent seeds. Through MASIPAG’s approach, farmers are being empowered to regain control over their genetic resources and agricultural technology. They have ceased from being passive recipients of destructive technologies, but are coming up with ones that are more beneficial and appropriate to their needs and capacities.

With these clear alternatives, farmers recognize that they do not have a need for Monsanto’s products and technologies. Additionally, farmers around the world should not only unite against Monsanto and other agrochemical TNCs, but they should also to adopt sustainable, organic agriculture – a healthier and better solution to hunger and poverty.