This essay was a talk given by the author at the Economics of Happiness Conference, Portland February 27 – March 1, 2015.

This past year, on an October afternoon, we carefully secured the last piece of luggage to our truck, said a half-smiling, teary-eyed goodbye to our house, and drove away from our University home. We called that home Aurora, and my wife and I had lived in her dancing lights for a few years during our work as lecturers in a university in Nigeria. She had blessed us with so many gifts, so many treasured memories: we watched Alethea, our one-year old daughter, spit out her first maybe-words in Aurora; we planted our first garden under her amused gaze, and experimented with fusing Indian and Nigerian cuisines when we weren’t attending meetings or marking examination scripts. In many ways we were born in Aurora, but now it was time to say goodbye – perhaps for the very last time.

As I drove away, careful to acknowledge the rattling protests of the humongous heap of books and unwieldy furniture we had accumulated during our sojourn as academics, I started to think about what we were doing – and how I didn’t quite have a name for it.

Our colleagues did. Some thought leaving the privileged positions we occupied in search of some kind of bohemian existence was a ‘mistake’; our students and a few friends, quite sad to see us go (even though we are expected to return to the University in 2 years), felt that our quest for a smaller life and keener days was inspirational. Between Ej, my wife, and I, our families wondered if we would earn just as much money as we had earned lecturing.

However, through the interstices of a thousand labels, behind the many names people had contrived to understand our transition and make sense of our movement, we had a song; a queer kind of knowing that didn’t lend itself easily to the logics and data about how life ought to be lived. We had something ‘else’, something wilder, something that would not be contained in the chaste and claustrophobic boundaries of an explanation: we had an Oríkì.

Where I come from, among the Yoruba people of Western Nigeria, names are important. They tell stories. My name is Adebayo. It means ‘I have met ease and pleasantness’ – a claim my wife would gently repudiate! My other name, Akomolafe, means something close to ‘one who teaches others the good life’. But it wasn’t until recent that I realized that I had a gift deeper than names could convey, more nuanced than a birth certificate has space to accommodate. An Oríkì is a cultural spectacle among the Yoruba; it is a deep spiritual reckoning with entangled worlds, hidden histories, peeping ancestors, and roving essences. It is often embodied by praise-poetry. It is said that one who doesn’t know his Oríkì has lost his spiritual story.

Oríkìs are like names, and yet they are very much unlike names – names are fixed, often brief, and often embarrassing – especially if your parents deem it fit to call you Voldemort or something that might be a fitting moniker for a biological curiosity. Oríkìs have no such fixity. If you happened upon a name, materially reconfigured and embodied, it might look like a red spot in an ocean of white – tame and unassuming, serving to identify a location, to mark a spot. An Oríkì on the other hand would look like fire – not a cultivated bonfire but a wild uncircumscribable harlot with golden hues as plumage, pulling in the sun and the sky and the soil into its dancing fury. To evoke an Oríkì is to wonder after the ‘essence’ of the recipient, to be in the moment while weaving a tapestry of adoration that might include dance, song, story, poetry and even gift-giving. It is a name without alphabets, the wonder beneath it all, names made keener.

So when, last year, a feisty Yoruba woman and academic colleague, bemused by the seemingly intractable assemblage of Indian-Greek names we had given to Alethea-Aanya, asked me if I had an Oríkì for our daughter, I didn’t know what to say. But it made me wonder if beyond names, beyond the neurotic rituals of language, beyond our best tools and analysis, there was an Oríkì for these times of upheaval and awakening.

Margaret Wertheim, in her recent article – The Limits of Physics – reminds us that all languages parse the world into categories – but not every aspect of our experiences fits neatly into those categories. While some cultures learn to respect ambiguities and definitional monstrosities as critical to the continuance of said cultures, other collectives become ‘obsessed with ever-finer levels of categorisation as they try to rid their system of every pangolin-like ‘duck-rabbit’ anomaly. For such societies… a kind of neurosis ensues, as the project of categorisation takes [more and more] energy and mental effort’, and, ‘whatever doesn’t parse neatly in a given linguistic system can become a source of anxiety to the culture that speaks this language’.

Today we are witnessing this exhausting anxiety as we reach the ends of our tethers. As dominant myths and single stories about what it means to be alive wither away, as climate change reminds us that we are perhaps not lords over nature as we used to think we were; as the growth paradigm reinforces an techno-consumerist empire of multinationals; devastated ecosystems, dwindling diversities and broken communities; as education-so-called strips from us our sincerest questions and inmost songs; as nation-states and representational politics fails to address our profoundest hopes and tensions, and as the prosperity and happiness promised by compliance to industrialized society hollows out, we are faced – as it were – with questions about what a more beautiful world could look like, and what we can do to make it real for us and for our children.

In an effort to make sense of all of today’s unfolding anomalies, many insist that today’s challenge, today’s gripe is between ‘us’ and ‘them’, between those who are awakened and those still asleep in the clutches of the Matrix, between the 99% and the 1%, between evil and beauty, between justice and injustice, between the North and the South or between both and the modern abstraction of linear growth, between individualized actions and systemic changes, or between an old story in demise and a new story we haven’t yet found words for. Most of us that will speak during this conference have strong and justifiable reasons to frame today’s chaotic changes as the tensions between a world imprisoned by a techno-economic, hegemonic ideology of growth, exploitative trade treaties, markets and a planet yearning to be healed by human-scaled economies, regulated banks, and renewed connections between nature and culture.

However, around the world, in puddles of unconferences and conferences, in symposiums and summits, in hotel rooms and school halls filled with activists whose faces bear tell-tale signs of wear and tear, of glimpsed hope, of reanimated despair, we are pushing our linguistic powers to an extreme; we are coming up with ever new ways of modelling how change really happens; we are inventing new categories of thought; we are tasking our volition storehouses and seeking smarter ways to rouse people to the urgencies of the hour; we are urging ourselves to be practical, to focus on the facts – the real stuff. But as our language gets more and more sophisticated, the more distant, it seems, a more beautiful world gets. Our increasing sophistication betrays our deepest anxieties about a universe that will not be comprehended, a cosmos that will not be summed up and reified in theory – no matter how passionate. A world that will not be named.

What all this means is that we do not know. We do not know how to resolve our current crises, how to bring about a more beautiful world; we cannot tell, with absolute certainty, whether strategy is preferable to being in the moment, or whether the North and South should indeed work together, or what it even means for a paradigm shift to happen. It is perhaps unresolvable in principle. We do not understand why we live in a world like this, why a techno-economic monolith rises and rises, its shadow greying our clouds and piercing our soils. And even though we have incredible conceptual and critical tools, we do not know how to come out of it – or even if that is the ‘right’ question. It seems the more we try to transcend the system, the more we behave just like it. Our uncertainty doesn’t exist because of a lack of evidence, or poor articulation, or any practical reason. Much to the contrary, the more we probe the furthest reaches of inner and outer space, the more we realize how entangled we are with the problems we strive to get rid of, with the ‘other’ we hope to save, with the systems we seek to switch off, and with the incomprehensible.

But what if our not knowing is our greatest asset yet? What if our journeys truly begin when we don’t where we are going? What if, like interstellar travellers in search of a home, our deepest feelings, the fluffy stuff we usually do away with, are just as important, just as real – or even more so – than our best statistics and our most practical insights? Could it be that even our smallest actions count in ways our system change dynamics are blind to? What if we could treat the unknown, the unthinkable, beyond data, as a resource – instead of an inconvenience?

Many elders from indigenous non-western cultures spoke about this. They urged us to slow down in times of urgency; they urged us to be at peace when we are lost – for it is then that other paths are noticed. They told us that the dark makes everything possible. What they meant, I think, is that we need a change of awareness, not a change of speed, in order to happen upon new and brighter days. The test was to see how entangled everything was – and how nothing stands alone; to see how we could not depend upon or trust ourselves to know the next moments. In a poetic sense, they might have said, ‘let’s stop pretending to be humans, and dissolve into our mother trees, into the clouds, into rock and fish.’ Perhaps if some of those elders were to address mainstream activism today – what with all our models, numbers, data sets, compelling theories and ideological divides – they would say that conventional activism valiantly attempts to address what only the whole can ‘do’, and that by moving towards what cannot fit our data sets – what might properly be called ‘magic’ – we recognize not only our worlds anew, but ourselves.

The elders would urge a keener sensitivity; they would call for an Oríkì. And I offer one today: that behind the names we give to our crises and the names we give to their proposed solutions, behind our most fervent ideals, beyond the pragmatism suggested by wielding numbers and graphics, there is a magic afoot, and the cosmos is probably mattering and unfurling in ways that weave together our discontent, our failures, our ignorance, our incoherence, our bumbling inadequacies, our victories, and our contradictions. And we see this magic at the edges of our linguistic systems, where causal relationships no longer adequately account for change, where agency and will and awareness aren’t individual attributes, swaddled in grey matter, but breathing in stone, in rock, in fountain, in yawning sun and teenage moon.

We are collectively being ushered to a very strange place – one which obstinately refuses the characteristic earmarks of location, of fixity, of dimension, and logical convenience. We cannot navigate our way ‘there’; we cannot increase our speed. Our ‘old’ fortes and categorical imperatives of thought such as cause, time, agency, direction, movement, and justice are no more useful than cardinal points are useful in outer space. The stitchery is coming undone, the Gordian knot is stretching out, and the rich tapestry of symbols and myth by which awareness was studiously guided, by which we thought ourselves righteous, is becoming threadbare. The great challenge of humanity – if there ever was or ever will be such a thing as ‘humanity’ – is to embrace the unthinkable, to move towards the anomalous, where a pregnant nothing swirls.’

Today, I celebrate the great and persistent work of amazing people and voices across the planet, and the utility of bold notions and invitations like localization – and their subversive presence in the world. I recognize the turbulence in our conversations about how to address change, and the riddles that are thrown up every time we consider competing worldviews and what they have to say about our times, who we are, and what we have at our disposal. I honour our furious intentions to rid the world of exploitative ideologies; I honour our anger, our despair, and our furrowed eyebrows. I honour our victories – however short-lived they may be. I make no claim that all these have some kind of ontological meaning deeper than experience itself. I merely urge us to see the wilder connections, the ‘deeper’ entanglements, and to perhaps learn to trust our deepest feelings – even though they defy conceptualization. I urge us to recognize that enchantment isn’t that much in short supply as, well, counterculture often grimly pretends it to be. I urge you to see that those things that don’t fit neatly into our models and data, into our great plans for systemic shifts, often matter the most.

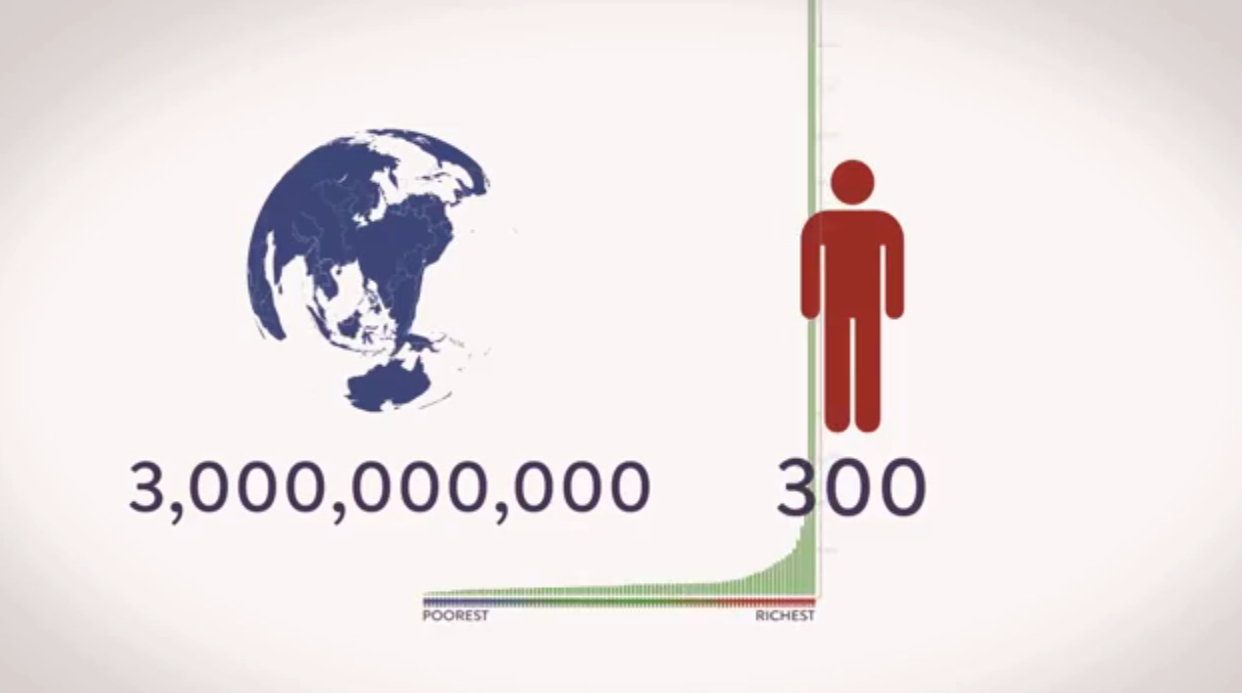

So remember, if you can, the miracles in your life: the first smile of your firstborn child – the smile that pierces the sky; remember how you felt knowing you are loved by another, how undeserving you often feel of another’s affections and attention. Remember the gift of food – the textures that have no names, and the sprightly bursts of colour and life where soulful meals are shared with friends. Remember the ones that have broken through the veil, and walked into the blaze of the distant sunset; remember their parting words, their fragile grip, their closing eyes. Think of how you feel knowing that 300 girls – none of whom you know – are still missing, 300 days after they were kidnapped from their beds in a Nigerian school, by men with trucks and guns. Think of what you’d give to have them returned – if your own daughter were one of them.

We live in Orikis, in colours awash with fragrance and memory and longing, in textures, in grief tinged with satisfaction, in joy stitched with the pain that it is finite, in shadows and light, in tears in spite, in moments that will not be named, in hopes the boundaries of which we haven’t tested, in feelings truer than words.

Our feelings may not have any utility, any practical worth outside the city square where the contests between concepts and labels play out, but that doesn’t make these little moments any less real or valuable – and perhaps recognizing this and resting in the peace that comes with this is our deepest challenge as a culture, and the end of it. In the words of Alice Fulton, ‘we have to meet the universe halfway; nothing will unfold for us unless we move towards that which looks to us like nothing: faith is a cascade’. Our deepest challenge today is to transcend not only the fear that we are alone, and that we are not doing enough – but the fear that if we do not do, nothing matters. We must (and I use ‘must’ with more than a sprinkling of hesitation) trust that things count even when they don’t add up.

Should we let go of our insights, or fall into a self-indulging hole hoping that things unravel in ways we expect them to? Does pointing to a ‘deeper’ place, a subterranean stream beneath the surface, mean that we should not speak out against fracking, against GMOs and mining? Is this another postmodern attempt to reduce everything to language, to say that the world isn’t real, to deny the very real corporate agendas that are framing insidious trade treaties like TTIP? Am I attempting some kind of reductionism with blue-sky allusions to magic and trust? Will any of that save the day? I don’t know. I think that our concerns with justice and the objects of these concerns are very real, but I suspect it would be a mistake to take as less real the ideas that our best data may no longer be enough, the insight that it is our culture – our ways of making meaning and combing experience for patterns (and not the earth) that is in crisis; our ways of responding to crises is part of the crisis. Let us get involved, let us turn inward, let us localize and do all in our power to call out the insidious activities of a global corporatocracy – but let us do so, knowing that what seeks to emerge, what wants to come about, will not necessarily lie at the end of our genius, or at the tips of our sophistication and our agendas. We can no longer conveniently brush away the idea that our toughest attempt to adequately represent the world in terms of social justice is occasioned by the very conditions that the world is produced from, and that what is seeking to emerge – though sympathetic to careful analyses and clarifying insights – is too promiscuous to be faithful to our efforts alone.

This is the Oríkì of our times, the subtle energies the call to localize gently coincides with, the soundtrack we often don’t get to hear when we huddle together to contemplate our precarious circumstances. This is the hidden motif we cannot yet understand, the emblem that is beaten into the monolith that guards the gates of the unknown country we are wandering towards. This is the ‘song’ we heard that solemn October day, as we left the campus to frame a life outside the spectrum of the normal – the soft, whispery tones that pierced through our best judgments and invited us to find our way by a different kind of faith. We turned to each other, Ej and I – as our truck crossed the University gates – and we sighed. We reached out for our hands, as if to anchor ourselves to what was most precious to us. “We are going home”, she said. And I knew, with a knowing that is powerful and true, that it was so.

Sumptuous writing! Question: if the Oriki of our times were to be reduced to just a few words, what would it be?

@Jeremy: I think that is the thrust of the article; Not everything can bereduced to ‘just a few words’. That is why we need oriki. Maybe the writer expects us to discover and compose an oriki “behind the names we give to our crises and the names we give to their proposed solutions, behind our most fervent ideals, beyond the pragmatism suggested by wielding numbers and graphics …”.

How? I don’t know.