The environmental movement will never save the planet unless it actively focuses its ire clearly on those who are most to blame for the crisis – the powerful.

There is no such thing as neutrality. If you are neutral in situations of oppression, you have chosen to side with the powerful. Desmond Tutu’s mantra is a key tenet of my recently adopted trade – journalism. It is often uttered by activists in movements against injustice – a cry of those attempting to shake people out of passivity. In the world I live in at least, it has become a platitude.

Like all platitudes, it’s easy to ignore. But to do so is risky. Whether it’s class or gender or race or sexuality or disability or nationality or religion or age, our civilization is built on pyramids of oppression. If politics is the art of living together, then any conversation about politics, including environmental politics, is in part a conversation about people of unequal power living together, and so a conversation about injustice.

This doesn’t mean that the injustice is always mentioned. Just as you can talk about the weather without referring to the climate, it’s possible to discuss politics without talking about power. When detailing the intricacies of a technical issue, it’s often easy to lay to one side the various pertinent inequalities. In individual conversations this can be fine. You can’t be expected to always mention everything about an issue all at once.

But as rain becomes rivers, conversations become narratives. And as rivers shape the land, narratives shape our politics. If a national political conversation takes place without discussing power, then we are being silent in the face of injustice. We are siding with the powerful. For most of the environmental movement, the main influence we have is our contribution to the flow of public debate, so how we use it has to matter.

Talking about power in general isn’t sufficient either. Because power is complex. Injustices are manifold. There is a word, coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw which explains this: ‘intersectionality’. “My feminism will be intersectional” Flavia Dzodan famously wrote “or it will be bullshit”. The point is that if you seek to attack one power structure but do so by treading on other oppressed groups, then you are still perpetuating oppression. This is an immoral thing to do. But if you believe that injustices stem from a system, and if you therefore wish to dismantle that system, then it is also strategically foolish. The person you just stood on should have been your key ally. We need to build links – intersections – between movements against all kinds of oppression. Our struggles are bound up together.

cartoon – @miriamdobson, Creative Commons

When feminists or anti-racists or disability rights activists call for intersectionality, the point they are making is that it’s not good enough to have feminist campaigns which ignore race, or disability, or class. Because to be silent in the face of injustice is to side with the oppressor. And too often, it’s easy to accidentally be worse than silent. We live in a racist, patriarchal, heteronormative, imperialist, classist, transphobic, disablist, xenophobic, ageist world. If we aren’t the person being oppressed by any one of those dynamics, then society is built in such a way as to encourage us, unthinkingly, to perpetuate them. Simply by standing still in our place in the pyramid, we squash those below us. Those injustices which stubbornly survive do so like genes or memes not so much because of those who mean to perpetuate them, but because of those who do it unthinkingly.

If these principles are true, then they are true for environmentalists too. In fact, before the word ‘intersectional’ was used to describe how power systems interlock, there was another term often employed to describe this web of different dynamics: ‘ecology’. When what is now ‘the Green Party’ was called ‘the Ecology Party’, the point wasn’t that it was in favour of trees (though it was). It was a metaphor: just as an ecosystem is an interlocking, mutually dependent complex, so too is human society. These days, it might have been called “the intersectional party”.

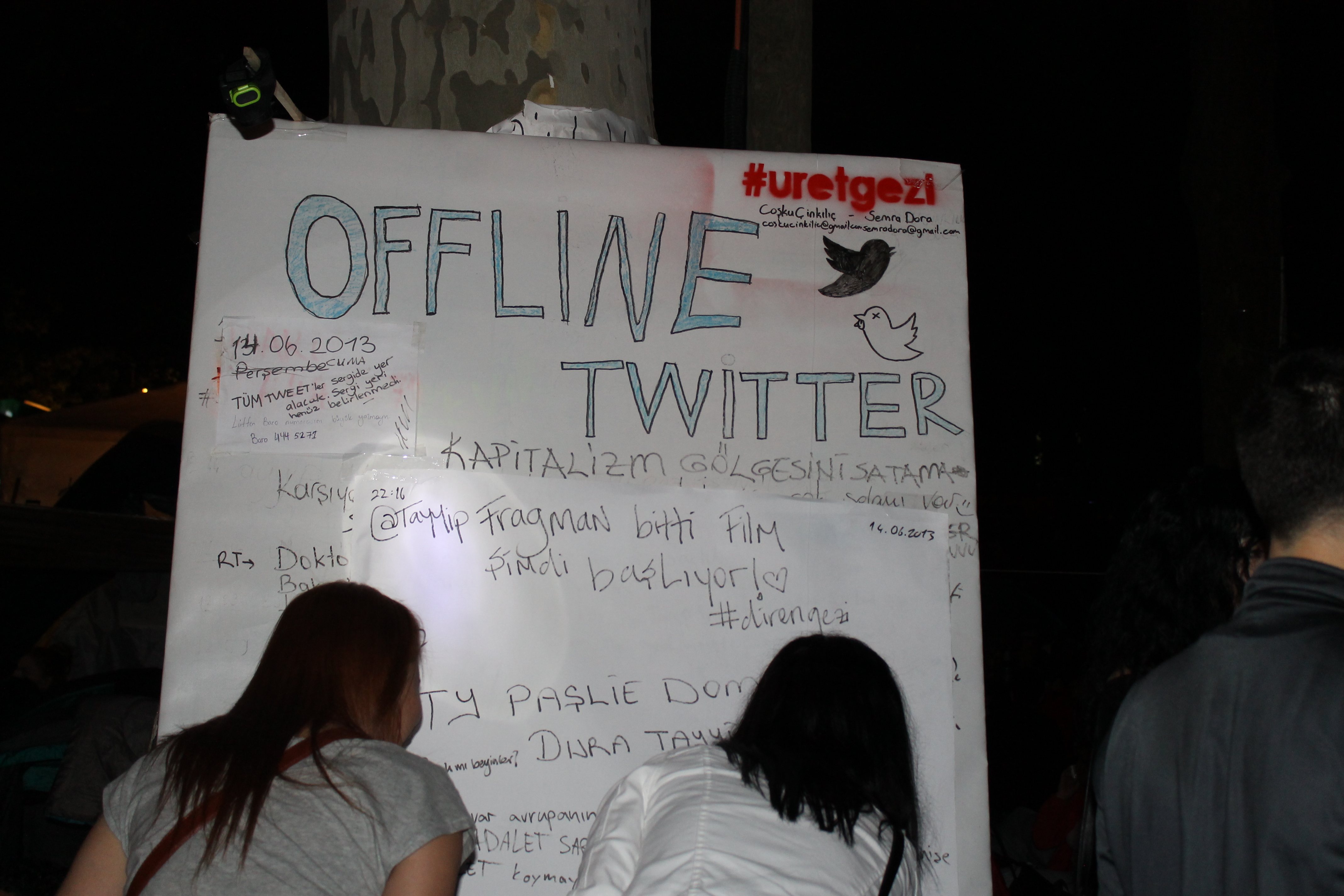

There’s a difficulty though. It’s easy to end up talking about saving the planet without discussing power relations. In fact, often it’s easier. Because it’s simpler to attract money if you don’t stand up to the wealthy. It’s not as difficult to court short term political support if you allow the old boy’s network to go unchallenged. But more often, people don’t talk about power for a more subtle reason – which is about neoliberalism, the manufacturing of consent and the grip of capitalist realism.

If we want to understand certain elements of our system, it’s often best to look across the Atlantic. There is an expression in American politics which I have always found fascinating: “what are your issues?”. Voters or candidates don’t have an ideology, or a vision or an analysis. They have ‘issues’. Because the analysis is all the same. They are all neoliberals. It’s just some are neoliberals who want to talk more about banning abortion or not whilst others are neoliberals who want to talk more about invading other countries or not and there are even some who are neoliberals who want to talk about not destroying the planet. Of course, many Americans yearn for a different politics entirely. But the official conversation doesn’t allow that. As the saying goes, it’s become “easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism”.

Capitalism turns politics from a power analysis into a shopping list. Neoliberalism survives by encouraging us to take its architecture as a given so we only argue about the colour of the paint on its walls. And too often, environmentalists just join in that conversation, and shout “green!” whilst ignoring that the building itself is a coal power station, and just talking more about the environment will do little to change that. But the building is a coal power station.

Capitalism, and particularly neoliberal capitalism, is a system which will always tend towards extracting more natural resource than is sustainable – because those who profit from it most are those who will suffer from this exploitation least; because it’s easier for those who own the centralised power of capital to control natural resources than it is for them to empower labour; because a sole concern for short term profit requires ignoring long term loss. Most importantly of all, if we want humanity to save the planet, we need to end a system which divides us, which teaches us to be selfish and drives us to forever ‘keep up with the Joneses’. As long as people are alienated from the world, they will do nothing to save it.

If humankind is to rescue ourselves and the earth upon which we depend, therefore, we need to see the system, in its complexity, not just take out a green pen and underline the word ‘environment’ on the shopping list of issues in the next election. And we need to understand that our allies are those who are oppressed by the same system; the people who suffer most from the neoliberal, patriarchal, xenophobic, transphobic, disablist, classist, racist, heteronormative, imperialist, ageist complex in which we live – the same people, not by coincidence, who will be hit hardest by almost every environmental crisis.

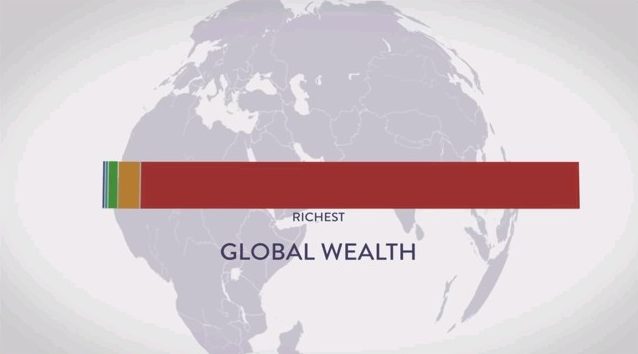

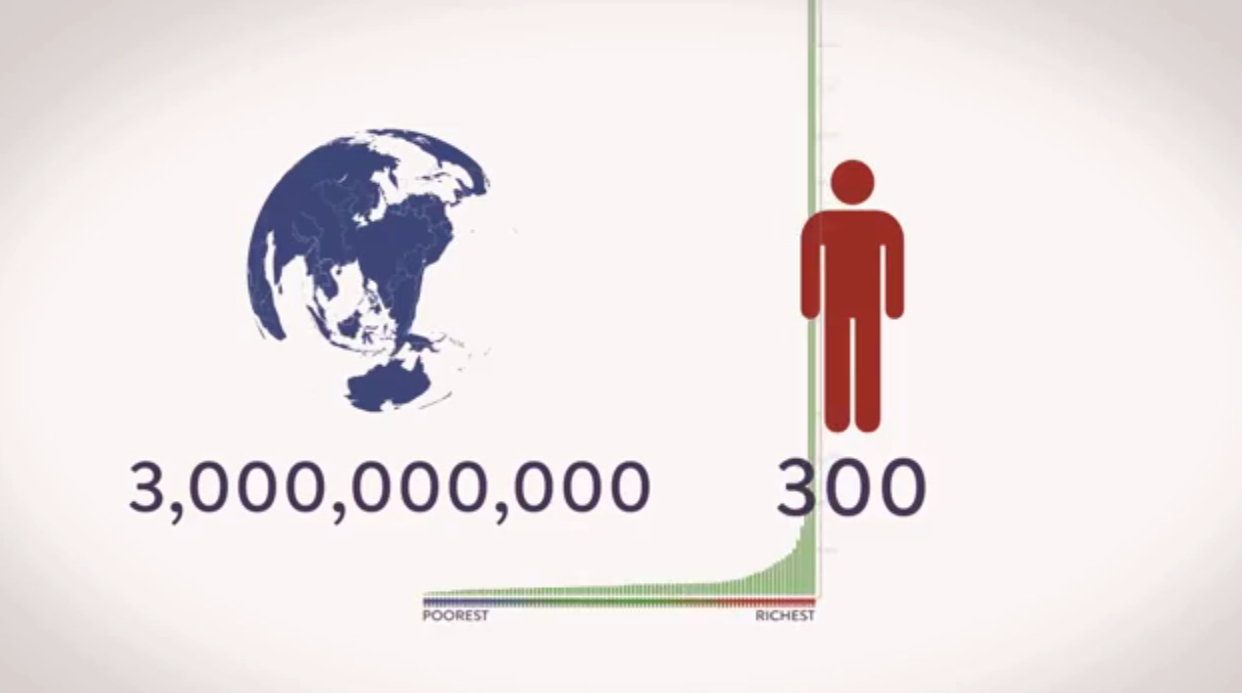

In fact, you don’t even need to believe that the whole economic system needs to be replaced to think that greater power equality is key to success for the environmental movement. When academics pulled together the data on income inequality vs carbon emissions across 138 countries from 1960-2008, they found that in the developed world, the more unequal a country is, the higher its carbon emissions. In fact, they found something even more remarkable than that. As they put it in the abstract of their paper: “for high-income countries with high income inequality, pro-poor growth and reduced per capita emissions levels go hand in hand”.

When explaining this remarkable finding, they cite another paper, which explains that “in more unequal societies, those who benefit from pollution are more powerful than those who bear the cost. Therefore, the cost-benefit predicts an inefficiently high level of pollution. This implies a positive correlation between income inequality and pollution”. I suspect the relationship is also because inequality rips society apart, and makes us unable to solve collective problems. But either way, it seems that equality of power is vital to reducing pollution.

What does this mean in practice? First, it’s important to see the link between power and responsibility. Those who have power are those who are almost by definition more responsible for causing the problems of the world, but they shirk this duty by forever shifting blame onto those with less power or onto the population in general. They rarely do this explicitly – almost never pointing a finger and crying “witch”. Instead, they do it subliminally. They tell the first half of a story, and let us infer its corrupted moral. We’re used to this outside the environmental context: “there’s a big deficit and that person’s cheating on their benefits” they say, or “there’s no jobs and lots of migrants”.

These narratives dominate because of the psychological power of blame, and because the individual elements of them are, to a limited extent, true: the odd person does break the social security rules, there is currently more immigration into the UK than emigration out of it. It’s just that the complexities of causation and correlation are swept aside, and by focussing on the ways that people without power can be blamed, and excluding the ways those with power can be seen as responsible, the public understanding is bent towards the interests of our rulers, and the true causes of these problems therefore become harder to solve. It’s not through lying that spin doctors deceive, but by selecting the truths they tell with care.

The powerful have long played the same trick with climate change: “there’s all this climate change” they say, “and you haven’t changed your lightbulbs”. Of course changing lightbulbs is good, but the effect is that the government can get away with not mentioning their friends in BP and Shell, and how they subsidise them; not talking about those who really have their hands on the levers needed to make real change happen as fast as is needed.

To be neutral on questions of responsibility is to side with the powerful, but too many environmentalists are worse than neutral. Too often, we use the power we have to make statements which are true (it would be a good thing if everyone changed their lightbulbs) but, by prioritising them above other statements which are also true (it would be good if oil companies were banned from taking oil out of the ground) in a context in which the powerful are blaming those with less power, we’re joining in on a blame game, and picking the wrong side. And telling someone they are to blame – more than they actually are – is just about the worst possible way to get someone on side. It’s no surprise we’ve descended into a ‘climate silence‘.

The most obvious example of shifting blame from the powerful to the powerless is probably Malthusians, who focus their energy on talking about the challenges presented by growing global population. Of course total human population is one of many factors contributing to overall resource use. But by focussing on statements which function to shift blame onto those who have lots of children (poor people), rather than those who have lots of power (rich people), they are, in effect, siding with the powerful, whether they mean to or not. They are making it less likely that real change can be secured.

Or we can look at the kinds of personal behaviour changes which tend to be called for. As Dagmar Vinz argues, campaigns highlighting individual carbon footprint reduction tend to focus on the domestic sphere. In the world as it is, this means it’s women whose behaviour is being challenged most, despite men arguably being responsible for more personal emissions and certainly holding more of the powerful jobs in the companies most driving climate change.

Another example is the habit of European NGOs who campaign on biodiversity to focus on former European colonies. Of course we should save the tiger. But three of the world’s six most endangered felines as listed by Scientific Americanlive exclusively or largely in majority white countries, including one in Scotland. A fourth lives in Japan. Why do we never hear about them?

An Iberian Lynx – one of the world’s most endangered big cats/Wikimedia

We should insist that Indians live alongside large carnivores, but are we not hypocrites if we don’t also demand that people in the UK (which, after all, has a lower population density than India) live alongside our own native carnivores – wolves and bears? Or at the very least invests much more in saving Scottish Wild Cats – which are as endangered as any Indian big cat? The princes are right to campaign against elephant poachers, but what of the Highland landowners, not so far from their Balmoral, who poison endangered Hen Harriers so that Britain’s upper classes don’t have competition for the grouse they want to shoot? Or do we only care about animals that are ‘exotic’?

While double standards perhaps aren’t the biggest injustice on their own, once you place them in the context of a former colonial relationship; and when you think of the way that imperialism was and is justified through orientalism by making peoples seem exotic and different in order to make them seem ‘other’, then perhaps we need to ask our wildlife charities to dedicate a little more time to restoring Europe’s formerly magnificent temporate rainforests as well as protecting those overseas? And when we think about who is implicitly blamed for the ‘poaching’ of African wildlife (it’s ‘poaching’ when poor people do it, when rich people do, it’s ‘hunting’), again, we need to tread carefully.

Again, blame is key here. A report from the Climate Outreach and Information Network highlighted that, during the recent UK floods, the public narrative was so keen to find someone to finger for the crisis that the climate change message was squeezed out of the national media. This tells us something key about why environmental movements have failed so disastrously in recent years. When something goes wrong, people want someone to blame. And because the most powerful are usually those who are responsible, they will always quickly take control of the public story, and ensure that the finger is pointed at anyone but them – this time, struggling Environment Agency staff.

The response that “well, this is really about climate change” just didn’t cut it when people were out for blood. In part, this is because of the psychological power of blame narratives, and that we have all been taught that we are all just about equally to blame for climate change. If people feel they are being allocated blame out of proportion to the power they have to change the situation, then they will, understandably, react badly. Had we said “blame the oil companies”, I wonder if it would have been a different story?

But an intersectional environmentalism – an ecological environmentalism – has to be about more than just not actively being oppressive. We can do better than not contributing to stories which blame or ‘other’ the victims of oppression. We must also understand that to be neutral in the face of injustice is to side with the powerful. And that means that we can’t talk about consumerism without differentiating between those who are driving it and those who are suffering from it; we can’t talk about growth without distinguishing between those who gain from it and those who are losing out. We can’t talk about climate change without being absolutely clear who it is that is driving the changes in our climate and who is suffering from them.

There is a habit in too much of the environmental movement, I fear, of talking about politics in a way which avoids questions of power, which fails to actively stand in solidarity with the marginalised. This isn’t because these environmentalists intend to oppress, but because messages which don’t confront power are promoted by the powerful. Messages which do challenge are made controversial, and attacked. And so life is easier if you never confront those who are actually most able to change things. But you don’t make any difference in the world by having an easy life, and unless we actively avoid the traps laid by oppressive systems we will inevitably fall into them. All of this has long been understood by the environmental justice movement, the climate justice movement, movements against environmental racism and in solidarity with indigenous people, eco-feminist movements and many more besides.

What they understand is that, ultimately those who profit grotesquely from killing the earth won’t save it, and neither will an oppressed, divided, alienated people. The activists, organisations and movements who have been working for years on the principle that environmentalism and justice are inextricably linked have long shown the way. If we wish to save the planet, we cannot be silent in the face of injustice: the path to sustainability and the route to liberation are two tracks on the same dirt road. My environmentalism will be intersectional, it will be ecological, or it will be bullshit.

Incredible, I’ve failled before to comprehend how feminist and evironmentalism movents correlated with each other, this text helped my brain draw the correlation between this two and others.

I only read truths here; Brazil (country where I live) has just experienced it’s biggest ecological catastrophe, caused by a transnational mining company, and while the govern, public minister and other entities are being blamed, the company still hasn’t done anything, and our media is talking more abou the events that happend in paris this week than this disaster. It’s passed the time for we to stand up to the power structures that are killing the world and making our lives miserable.

thanks for the comment, I’m really glad the piece was helpful! Good luck in Brazil.