Tell yourself it’s easy to fix—and that you’re not responsible for it.

Hope sells. Not quite as well as sex, but certainly better than despair. Politicians know this, marketers know this, and the politicians and marketers in the organizations concerned with global poverty know this.

There is a line, though, that separates real, meaningful hope from marketing and spin. At the upcoming UN General Assembly, we are all about to be told some stories as part of what’s being called the “world’s largest advertising campaign” by the UN, NGOs, governments, and large corporations. The campaign is to sell us on the new global plan to tackle poverty. It’s up to each of us to determine whether these stories are full of hope we can believe in, or just a big serving of marketing and spin.

This plan, called the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is going to be launched later this month. Heads of State from all over the world will descend onto New York to formally sign it. There will be fanfare, celebrity endorsements, concerts, and photo ops, and a general air of “let’s all celebrate what we’ve achieved so far, and what we can do together next.”

The “what we’ve achieved so far” part of the equation is summed up in the idea that global poverty has been halved since 1990; testament—so the official logic goes—to the great success of the last big poverty plan, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). And this leads effortlessly to the “what we can do together next” part, which is, largely on the basis of this progress, actually eradicate poverty “in all its forms, everywhere” by 2030.

It’s an almost irresistible story. What craven, miserable misanthropes could possibly take issue with it?

Well, that depends on how true it all is. If it’s not true, we should all take issue with it, and withhold our support. And there is, unfortunately, every reason in the world to question the deployment of such grand hope to sell this particular plan.

There are few things more important when it comes to the collective endeavor to rid this world of the violent and terrible blight of mass poverty than whether we all basically believe that the world is heading in the right direction right now, which is what the official story wants us to believe. If we believe that, we are more likely to be politically passive, thinking that things are basically in hand.

If things aren’t as rosy as the official story would have us believe, however, and there is reason to believe the plan can’t deliver what it promises, then we are more likely to demand different approaches from world leaders and, indeed, each other; we are more likely to demand change in the direction this plan—and the system that surrounds it—are set to take us in.

This isn’t an academic question; 4.1 billion people currently live on less than $5 a day, and almost everyone on earth will be affected in some way by the UN’s plan to decrease that number. The least we should expect from the people selling it to us is truth and honesty.

We made this video to highlight three particularly important questions we think need asking by as many people as possible:

1: HOW IS POVERTY CREATED?

There is an assumption buried deep in the logic of the SDGs that mass poverty is essentially a natural condition that occurs in the absence of any action to overcome it (you can check our assessment of this in our linguistic analysis). But this assumption isn’t accurate at all. It simply takes what feels like intuitive common sense about poverty at the individual level and presumes it works for countries and, indeed, the whole world, over time. But is that right? Is it true that everyone is born with equal access to the means of ensuring they never live in poverty? Do power dynamics between countries have any part to play in who gets rich and who doesn’t?

Consider this: there has been a globalized economy for at least 400 years (you could easily argue it has existed for considerably longer). In that time, some parts of the world have increased their wealth exponentially, notably those who have created and run systems of control and domination stretching around the world in the form of empires, slavery, and colonialism and, in more recent years, trade deals and structural adjustment programs.

It’s hardly a strange idea, that those with the money make the rules, and this is a truth that is writ large in the global economy today, and has been for practically all of the last 400 years.

In light of this reality, if it seems to you that there is a lot more to mass poverty than what the individual has control over, then you might want to question why the SDG framework denies this. And what this denial says about their promise to end poverty by 2030.

2. WHY IS GROWTH THE ONLY ANSWER?

Right now, economic growth sits at the root of the SDG plan to tackle poverty. The SDGs are aiming for at least 7% per year in the least developed countries, and higher levels of economic productivity across the board. Goal 8 is entirely dedicated to this objective.

This feels intuitive and logical. If economic growth equals more money, and poverty equals a lack of money, then economic growth equals less poverty. It stands to reason. But, now consider this: since 1990, global GDP has increased 271%, and yet both the number of people living on less than $5 a day, and the number of people going hungry has also increased, by 10% and 9% respectively. Add to that the wage stagnation across the developed world, and increasing inequality both within and between countries pretty much everywhere, and the shakiness of this basic logic becomes evident. Aggregate economic growth does not translate into less poverty; the stated objective of the SDGs.

Maybe this would only be problematic, something that could be fixed by tweaking the growth model while keeping the basic imperative in place, were it not for the second part of the problem. The imperative for every country, every company, and every individual to constantly grow their material wealth is destroying us, in the most real and painful way. The consumption-driven mechanisms we use to achieve it, and the GDP measure we use to define it, have us locked on a path to ruin by actively encouraging us to treat finite natural resources as if they were infinite, and prioritize the growth of the money supply over everything else. Said another way, the perceived moral imperative for economic growth actually contradicts the laws of nature.

Are there any other reasons why endless growth, everywhere, might be so attractive to the designers of the SDGs? Could there be reason buried in the fact that, in recent years,95% of all income from growth has gone to the richest 40%? This leads us to the third question.

3: WHO’S DEVELOPING WHO?

The common assumption is that the rich countries of the global north, through foreign aid programs and by participating in projects like the SDGs, are helping the less wealthy countries of the global south develop. But how true is this?

Right now, for every $1 that is given in foreign aid to the global south, around $18 is taken out by other means, most notably rigged trade deals than benefit the most powerful countries and corporations, debt repayment on debts already paid off many times over, and massive tax evasion and other forms of corruption, committed by political and business elites north and south, and facilitated by a large and growing web of tax havens. So in the grand scheme of things, who’s actually developing who?

The answer to this question will also affect your opinion of the SDGs. They don’t have a lot to say about this dynamic, and in fact riff pretty heavily on the basic idea that it’s the north that is the generous party. They do acknowledge both the vast level of illicit finance, and that the global financial system is relevant to their project, but capture their level of concern in vague statements about the need to “enhance global macroeconomic stability” through “policy coordination.” There are no specific responsibilities for anyone, or any actual targets.

This is a very rich world, filled with determined, smart, compassionate people and mind-bending technology. Everything we need to tackle poverty and climate change is at our fingertips. We just need to add to this mix of possibilities the honest and credible intent. Honest and credible.

We treat the goodwill of people lightly at our peril. Every time we over-hype a claim today, we create the conditions for disillusionment and political disengagement tomorrow. It is short-termism of a very damaging kind. Although it may feel harsh to question the idea that the SDGs can eradicate poverty by 2030, we owe it to ourselves—and those that will come after us—to do just that.

This article was originally published on FastCompany Exist on 2nd September 2015.

I had a look at the FAO report that you referred to concerning your statement that there as been a 9% increase in people going hungry, and your statement seem to be wrong. According to the report the number of people that are undernourished has decreased from 1000 million to 868 million and the percentage of people that are undernourished has decreased from 18.6% to 12.5%.

Though the situation does not seem as bad as you write above, I agree that the development is not good enough, that economic growth is overrated as a solution to poverty, and that current rules mostly benefits the already rich. However, I have gotten the impression that the proposed sustainability goals overall entails improvements in the UN policy, including for example Goal 10 to “Reduce inequality within and among countries” and a better coordination between the different UN bodies.

Hi Rickard. Yes, that is what the report concludes, but if you look at the methodology, and the history of the numbers, the claim does not hold water.

When the Millennium Campaign was formally launched in 2000 they chose a base year of 1990, which made the hunger trend appear a little bit better by allowing them to claim some of the gains made by China in the 1990s. They also decided to dilute the goal by focusing on reducing the proportion of hungry people instead of the absolute number. As with the poverty numbers, this statistical sleight-of-hand improved the narrative significantly, but there was no getting around the blunt fact that the hunger headcount was still a damning 21% worse in 2009 than it was in 1990.

All of this magically changed in 2012. With only three years to go before the expiry of the MDGs, the FAO announced an “improved” methodology for counting hunger. And the revised numbers delivered a rosy tale at last: while 23% of the developing world was undernourished in 1990, the UN was pleased to announce a reduction down to 15%. The goal still wasn’t in reach, of course, but at least the UN could claim some progress.

How did they pull this off? By pushing the definition of hunger to rock-bottom levels. The new methodology counts people as hungry only when their caloric intake becomes “inadequate to cover even minimum needs for a sedentary lifestyle” for “over a year”. The problem is that most poor people don’t live sedentary lifestyles; in fact, they are usually engaged in seriously demanding physical labor just to stay alive, so in reality they need much more than the UN’s calorie threshold. The average rickshaw driver in India, for example, needs 3,000-4,000 calories per day.

What’s more, according to the new measurements, people who have serious deficiencies of basic vitamins and nutrients (which affects 2 billion people worldwide) are magically not counted as undernourished as long as they can get enough calories to keep their hearts pumping. And if you happen to be starving for 11 months out of 12, for some reason you don’t count as hungry. Apparently it’s enough – as far as the development industry is concerned – to simply keep people alive, just to satisfy the metrics, while caring little about the kinds of lives that they are able to live.

It’s worth pointing out another suspicious flaw in the new hunger numbers. They report that undernourishment was constant – or even decreasing slightly – during the massive food price spikes in 2008 and 2011, which were spurred by reckless financial speculation in food markets led by Goldman Sachs. We know that this took a serious toll on people’s access to food, and the fact that the new methodology doesn’t capture this impact makes it highly questionable.

Yale Professor Thomas Pogge has been instrumental in bringing this scandal to light. In fact, there’s a debate underway right now about whether the new metrics are fit for purpose for the new SDGs. According to Pogge, they are not: they “vastly understate the number of chronically undernourished.” “Somebody, somewhere, needs to speak the truth, needs to say that the poor have been dramatically betrayed.”

The truth is that probably closer to 2 billion people, nearly a third of the human population, do not receive adequate food. 3.1 million children die each year from hunger. 160 million children under the age of 5 are stunted because they lack basic nutrition. And this tragedy persists in the face of what has surely become one of the most-repeated facts of our time: that we collectively produce enough food each year to feed everyone in the entire world – at the generous level of 3,000 calories per day.

On the Reducing inequality – again, you need to scratch beneath the surface and interrogate the language.

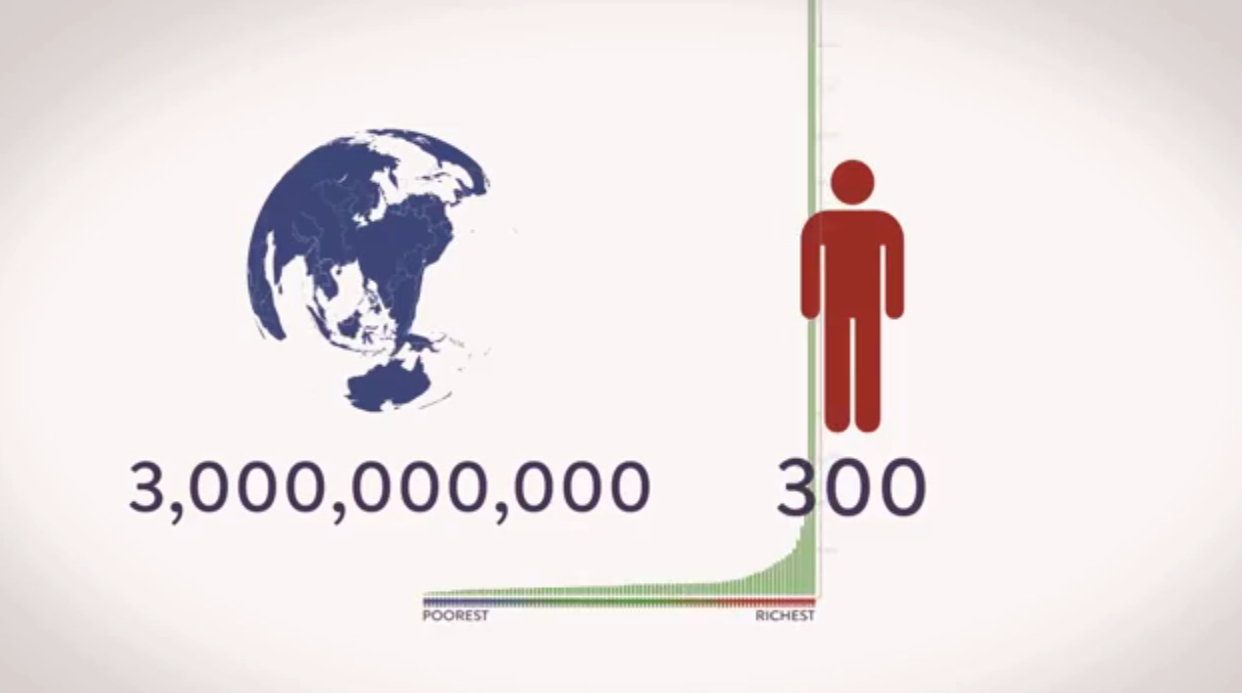

The richest 1% of humanity will very soon own over half of the world’s private wealth. It would take only modest reductions in inequality to deliver large increases in the socioeconomic position of the poorer half of humanity.

The SDGs do talk about reducing inequality. However, their prescription is technocratic, obscure and wholly incommensurate. For example, Goal 17 states that by 2030 they will “progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average.” It is hard to imagine a less robust or ambitious goal. By this measure, inequality can grow without limit until 2029, so long as it then begins to be reduced. The SDGs thus fail to endorse the only means that can achieve their stated goal of ending poverty: substantial inequality reduction, starting now. In effect, they perpetuate severe poverty and leave this fundamental problem to future generations.