John Ashton was the UK Government lead negotiator in global climate talks for six years. He just gave this speech to an energy industry conference in Paris. He addressed it to Ben van Beurden, CEO of Shell. Please take the time to read it. It is as beautiful as it is powerful.

Conseil Francais de L’Energie

4th European Energy Forum,13 March 2015, Hotel Intercontinental, Paris

Speech by John Ashton

Less worldly, more wise

A Letter to Ben van Beurden

Dear Mr van Beurden

One month ago, at the IP Week dinner in London, you gave a speech calling on your peers, as you put it in your title, to be “Less Aloof, More Assertive” on climate change.

Given your prominence as CEO of Shell and the resurgence of interest in climate, your speech has rightly provoked debate. Perhaps I could set out some reflections that passed through my mind as I studied it.

I feel privileged to be doing so from this platform. I hope the CFE family, and Jean Eudes [Moncomble, CFE Secretary General] particular, will see this as an appropriate way of honouring their invitation. Your speech, Mr van Beurden, was after all an appeal to your industry, which is strongly represented here today. Most of what I am about to say applies well beyond Shell.

The title of your speech is intriguing. I have been involved in this debate for twenty years, six of them as the UK’s diplomatic envoy on climate change. During that time many adjectives have been applied to your industry – not always fairly. But nobody has ever accused you of being aloof.

Yes, there have been more strident voices. You have spoken in measured terms, in prose not poetry, with the quiet confidence of those who know they never have to shout to be heard. And you have sometimes chosen to express yourselves behind closed doors, or through others, rather than out in the open.

You have an undeniable interest in the choices society makes about climate change. But you have been sophisticated in pursuit of that interest, as you perceive it. From the start, nobody has been less aloof, more assertive, nor more influential than the oil and gas industry.

For a leader in that industry now to express concern that it is not close enough to the climate debate sounds a bit, if you’ll forgive me, like a fish protesting that the ocean it swims through is not wet enough.

The summary that accompanies the published text of your speech also catches the eye.

It anticipates an “energy transition”. But it foresees no change “in the longer term” in the drivers of supply and demand for oil. And it urges the industry to “make its voice heard” at the COP21 climate conference. This would add “realism and practicality” to a conversation from which, by implication, these attributes are currently lacking.

In other words, the energy transition to come will be an unusual kind of transition. It will have no structural consequences for the energy system itself, or at least for the markets on which your business model depends.

But this prospect, your summary suggests, is in jeopardy. The unrealistic and impractical voices that currently dominate the climate debate want to use COP21 to unleash a more threatening kind of transition. To prevent this, the industry must overcome its habitual reticence and raise its voice.

Engagement, with delusions of aloofness. Commitment, to a transition that ends where it began. Such cognitive dissonance suggests, even before we get to the text, that your speech may say more about the state of mind of your industry than the external conditions that prompted you to speak out.

Those who have dedicated their lives and careers to your industry must sometimes feel your virtues go unacknowledged while the sins of the world are heaped at your door.

The story of civilization is an energy story. Nobody has told it better than your colleague Frank Niele in his classic book on energy, which should be better known.

The most gripping chapter of the energy story spans the last 150 years. That is your story, the story of oil and gas. As in any human endeavor, there have been episodes of frailty, venality and hubris. But so too have there been epic, even heroic deeds.

From beneath soil and sea you have wrested oil and gas in unimagined abundance, often under technically challenging and physically dangerous conditions, never failing to meet the demands of energy-hungry societies.

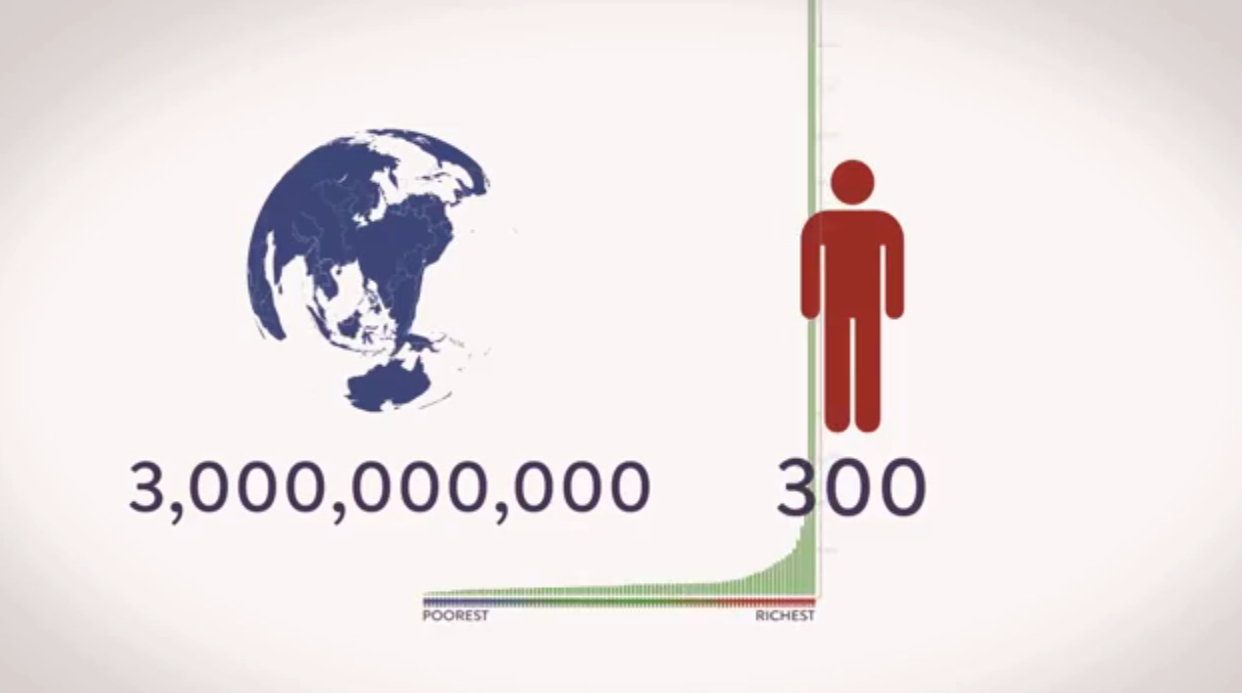

It would be only human if you were to reflect occasionally that without you, the prosperity enjoyed by billions, and aspired to by billions more, would not exist. Human beings would be living shorter, more difficult lives, exposed to more hazards, trapped within narrower limits of experience, opportunity, and imagination.

And as your industry has grown to maturity, it has forged strong values, nowhere stronger than in Shell itself.

You are rooted in reality. With so many physicists and engineers it could hardly be otherwise. While our political discourse descends ever further into a miasma of dogma, artifice, spectacle and celebrity, you have done your best to remain reality-based. This is surely a virtue.

Nobody should think that words like “realism” and “practicality” issue casually from your lips.

You have never recoiled from the future. You have striven to solve its puzzles and bend it to your purpose.

I am a lapsed diplomat (and a lapsed physicist). From early in my career the Shell Scenarios were seen in the British Foreign Office as the pinnacle of their art, and their then impresario, Ged Davis, as a modern Merlin.

Later you were way ahead of governments in sounding the alarm about the dangerous nexus of global risks linking food insecurity, water insecurity, energy insecurity and climate insecurity.

In Shell you quickly grasped the growing importance of cities, and the expanding cohort of newly affluent citizens, as a global shaping force. This is now orthodoxy. But Dave Sands and his team at Shell were onto it more than a decade ago.

Stronger even than the tug of reality and of the future, one instinct has long defined your industry.

Often in politics the first reaction to a new challenge is to ignore it and hope it will go away. There are enough problems.

If it won’t go away, the second reaction is to delay. If you can push it into tomorrow, it might yet go away and anyway, in politics, tomorrow never comes.

At your best you do not ignore or delay. You look for a response that turns challenge into opportunity.

Drilling in extreme conditions; converting gas into liquids for shipment around the world; capturing and sequestering carbon dioxide – whenever you have bumped into a frontier, especially a frontier of engineering, your urge has been to break through it. You accept, grudgingly, the constraints imposed by the laws of thermodynamics. But within them no challenge has hitherto been too daunting.

Now you are being asked to play your part in the response to climate change, the biggest challenge your industry has ever faced.

Surely, you might reasonably think to yourselves, we should acknowledge in return your role in bringing within our reach the fruits of modernity. Those fruits have turned out not to be as sweet as they seemed. But it was we who desired them. You never had to force them upon us.

It is in truth not your fault that climate change is a hard problem. Though your industry must bear some responsibility for our failure so far to face it, that is not exclusively your fault either.

But the choices of your generation of CEOs will be decisive, not only for you as corporations but for the eventual success or failure of our response to climate change.

That is why you will be held relentlessly to account for those choices; why what you said last month invites forensic scrutiny.

Every speech tells a story. And beneath the story on the surface there is always another, told more subtly, about the compulsions, desires and anxieties that animate the first.

Only if each story is true to the other; and only if each is rooted in an experience of the world shared between speaker and audience; only then will the speech truly be heard.

Not one story but three. The story of the mask you show, the story of your face beneath it, the story of the world.

The story of your mask last month was clear.

You accept the “moral obligation” to respond to climate change, including for your industry. COP21 will be crucial. The stakes here in Paris will be high.

But meanwhile, there is a march of progress. As we stride forward, a golden thread of growth links the size of the economy, demand for energy, and demand for oil and gas. This should continue indefinitely. Yours will remain “an industry that truly powers economies”, as “the world’s energy needs will underpin the use of fossil fuels for decades to come”.

You do not, it appears, see climate change as a threat to the steady march. But you fear we might be overzealous. Excessive concern for the climate might lead us to break the golden thread by constraining the combustion of your products.

This too is a question of morality. It is as you see it in conflict with the question posed by climate change itself. How, you ask, can we “balance one moral obligation, energy access…. against the other: fighting climate change”.

Your response is that we should ease off on climate. We can have a transition but it cannot transform. The aim, in any meaningful timeframe, should not be an energy system that is carbon neutral nor even low carbon.

Instead we must settle for “lower-carbon”, whatever that means, to allow us the “higher energy” that “makes the difference between poverty and prosperity”.

And so the story of your mask leads inexorably to the conclusion that no choice is needed after all. Only one approach is morally and economically available. It is not transformational. It proceeds by very small steps.

And as for fossil fuels, “rather than ruling them out, the focus should remain on lowering their… emissions”.

You have no compunction in immediately excluding coal, the product of a rival industry, from this endeavour. But that is to accommodate a shift to gas, not faster deployment of renewables (which would divert investment from gas); still less energy efficiency, which you do not mention at all.

You urge the adoption of carbon capture and storage, which Shell has, yes, pioneered. But you offer no proposal to overcome the main obstacle, the extra costs it imposes.

There is no engineering reason why dozens of large CCS installations should not already be running across Europe. I helped negotiate the New Entrant Reserve financing mechanism in 2008, working with many others including your colleague Graeme Sweeney. We thought then that we had broken through on financing.

Instead: still no plants. Your Peterhead project could be first. But with no compact to share additional costs between taxpayers, consumers and shareholders, CCS at scale remains empty talk.

You call for “a well-executed carbon pricing system”. Leaving aside the poor execution of the European Emissions Trading Scheme, a carbon price can only ever drive change at the margin. And it will not do that as well in real life, with all its uncertainty about forward prices and conflicting price signals, as it will in a well-behaved model.

It is now widely understood, except by those who live inside such models, that a climate response based primarily on a carbon price will deliver only marginal change. Politically it serves as a brake on ambition not a stimulus, especially when accompanied by an aversion, also evident in your speech, to hard caps on emissions.

That is the story of your mask: a manifesto for the oil and gas status quo, justified by the unsupported claim that the economic and moral cost of departing from it would exceed the benefit in climate change avoided.

Beneath the mask is the face. Its story is encoded in language and tone, and it does not match the mask.

You reject “stereotypes that fail to see the benefits our industry brings to the world”. But you resort freely to stereotypes yourself, to attack those who want more ambition.

You and those who agree with you have a monopoly on realism and practicality. You are “balanced” and “informed”. Your enemies are “naïve” and “short sighted”.

And you accuse them of wanting “a sudden death of fossil fuels”. No phrase in your speech is more revealing. Nobody is asking for this and if they were they would be wasting their time. But the Freudian intensity of your complaint flashes from the text like a bolt of lightning.

Moreover, although you acknowledge doubts about the credibility of your industry, you don’t address them. You speak, as it were, peering down, with authority and detachment, at a world that should self-evidently look the same to others as it does to you. And from that height, you seem to be want us to believe that the issue is not how to deal with climate change but how to do so without touching your business model.

You are not detached, and in reality your authority is compromised by your obvious desire to cling to what you know, whatever the cost to society.

For a leader in the oil and gas industry to call for continued dependence on oil and gas will sound to most like special pleading. Unless you acknowledge this, what you say won’t be truly heard.

Narcissus gazed into the pool and was dazzled by his own reflection.

Climate change is a mirror in which we will all come to see the best and the worst of ourselves. In that mirror you seem to see the energy system you have done so much to build and to find it so intoxicating that you cannot contemplate the need now to build a different one.

There is a touch of narcissism in the story of your face.

The paranoiac fears conspiracies that do not exist. You fear a non-existent conspiracy to bring about your sudden death.

There is a touch of paranoia in the story of your face.

The psychopath displays inflated self-appraisal, lack of empathy, and a tendency to squash those who block the way.

All these traits can be found in your text. There is a touch of psychopathy in the story of your face.

I am sure you are not yourself narcissistic, paranoid, and psychopathic. But yours is part of a collective voice, and those attributes colour that voice.

The story of the mask and the story of the face behind the mask. The one, a picture of reason. The other in the grip of all too human emotions. They are not at peace with each other. Nor with the world.

The story of the world is as old as antiquity. It is the story of the writing on the wall. The warning to the last King of Babylon at his last great feast that he has been weighed in the balance, as it is written in the Book of Daniel.

The high carbon, resource-profligate modernity you helped build is a new Babylon. Every bite from its fruit poisons the tree from which we pluck it. King Belshazzar of Babylon plundered goblets of gold from the Temple of Solomon. We take our plunder from an ecological fabric we no longer recognize as our first Temple. But if it crumbles we die both in body and in spirit.

Climate change is the writing on our wall.

If we heed it we can repair our Temple and avoid the fate of Babylon. If we don’t, we, too, fall.

You know this. If you didn’t, your exploration of the nexus must have shown you.

Governments have obligated themselves to do whatever it takes to keep climate change within 2°C. I once heard an industry peer of yours dismiss this. Politicians, he said, had promised it cynically to keep NGOs off their backs. But there was no will to act on it. At the table was one of your own predecessors, who did not demur.

The 2°C obligation is not going to go away. It will be reasserted at COP21, which should now also state clearly that this means carbon neutral energy by mid century. 2°C was not a casual reaction to civil society impossibilism. It was a political judgement, informed by science, about the threshold beyond which climate insecurity is likely to become unmanageable.

The commitments made at COP21 may still fall short of a 2°C response. But the forces now at work will act inexorably to push up not rein back our ambition.

Your strategy seems to be to try to hold the line until the door finally closes on 2°C. But governments cannot walk away from their obligation. They would have to explain what had changed to justify doing so. Everything we have subsequently discovered invites more urgency not less. The real threat to prosperity lies in too little ambition not too much.

The only means we have to make choices in the public interest across society is politics.

I have lived in a period when politics has been linear, and therefore predictable. You are skilled at navigating linear politics. Corporations became ever more skilled at rigging the choices made by linear politics for their profit against the public interest. That is one reason why linear politics ending.

We are now entering a period of politics that is non-linear, politics whose outcomes will, from the old frame of reference, your frame of reference, be harder to predict. You are not skilled in navigating non-linear politics.

There is no feel for politics in the Shell Scenarios. That didn’t matter when politics were linear but it does now.

Non-linear politics will welcome new voices. Cities. Communities. Young people. Women. Consumers. Policy takers will become policy shapers.

Their voices will act like a ratchet, driving up ambition on climate.

Businesses exposed to climate risk will demand more ambition.

Businesses delivering carbon neutral energy will demand more ambition.

Businesses not locked into fossil energy supply chains will want to end up on the winning side and will welcome more ambition.

Businesses holding out for less ambition will no longer be able to take cover in a big tent, no longer be able to pretend to be part of the solution when their choices belie this. They will have nowhere to hide.

The low carbon economy is starting to take shape and it works.

Germany has embarked on an irreversible restructuring of an electricity system that will be powered largely by renewables.

You have misread this. You point to generous subsidies for renewables in Germany. But these are the legitimate product of political consent. You point to baseload coal. But, strangely for an engineer, you fail to note that this is transient noise in a structural transition whose signal is the rise of renewables.

You deny your assets will be stranded. True, first tier assets are cheap, and those that are heavily invested in tend to bear fruit quickly. But your case also assumes failure on 2°C and rates of renewables deployment long surpassed by reality.

The Bank of England is watching the carbon bubble. Bloomberg screens include a carbon risk valuation tool. The divestment movement may still be small but it is rallying young people, has moral authority, and can now make a prudential case as well as an environmental one.

Writing on the wall. Story of the world.

A friend of mine, who rose high in another energy company, told me of the remorse that overtook him when he retired at having lived a lie on climate.

Clean energy startups in the US are full of refugees from fossil energy.

E.On’s best staff clamour to join its renewables business when the company splits. Few want to keep making legacy power from coal and gas.

I wonder if people inside Shell feel the pull of the same forces.

They find themselves in an industry squeezed in a three way vice. Investors and regulators will increasingly want to derisk unburnable carbon and future climate policy. New resources cost ever more to bring to market, in dollars and reputation. Regardless of the oil price now, its volatility will make new investments more of a gamble.

Is this industry still as inspiring to your younger colleagues as it was when you entered it?

Everybody except the real psychopath wants to feel part of the common good. Your company is full of good people. But good people can make bad choices in an institution clinging to a bad idea.

Your own position is unenviable.

A gap has opened between wealth (which is high carbon) and value (which is low carbon). Non-linear politics is the response of the people, your customers, to that gap. For a while the gap was narrow enough to straddle. But no longer.

You cannot choose wealth and value. You cannot choose to transform and to struggle against transformation. You cannot choose high carbon and low carbon.

105. Now you must pick a side and accept the consequences.

It’s an agonizing choice. Either way, the costs will be huge. Either way, you will be rolling the dice. Nothing in your experience prepares you for this moment.

Choose wealth and you could stay, for a while, in your comfort zone, clinging to an old business model. Even in the three way vice it will remain viable for some time. Demand for your products will grow before it falls.

While this goes on you could keep trying to rein back ambition on climate. Your industry, acting strategically together as a political brake, probably can hold out until 2°C becomes an impossibility of engineering and thermodynamics.

But it can’t do that without being weighed in the balance, perhaps on your watch. Confidence would drip away. Talented young staff would drift away. Respectability, already tarnished, would drain away. Drip. Drift. Drain.

Or you could choose value. You could accept squarely that your E.On moment has come, that the days of yesterday’s business model are numbered, that the challenge now is to manage its decline and build alongside it a new business fit for today, albeit that this is harder for an oil and gas company than it is for a utility.

You would be accused by some of tribal betrayal and commercial lunacy. You really would be lifting the lid on carbon risk. Your share price would suffer, at least in the short term.

But you would be buying the chance to renew your business by design, not by default in response to shocks.

There would be no need for a mask. The face could look the world in the eye and see itself reflected back.

I do not know what the new business model looks like. You won’t begin to know yourselves until you accept that as an instrument of the common good the old one is already dead.

But I do know what the world needs to see if it is to accept your company as part of the solution and no longer part of problem.

Stop frustrating ambition.

Talk to us about how you will play your part in a 2°C transition.

Tell us the inspirational story of that transition, backed by your knowledge and experience. The electrification of vehicles and heating; the decarbonization of electricity; new frontiers in efficiency. A new golden age of energy.

And don’t tell us through crocodile tears that this will all take a long time. Tell us what you will do to hasten it, and what you need from government to do it faster.

Come clean on your 2°C carbon risk, and get out of investments that would increase it.

Stop pretending that gas is part of the answer to climate change, rather than a necessary stage in a transition to be kept as short as possible. Stop pretending that gas will always crowd out coal rather than renewables, that it won’t blur the political focus we need on efficiency.

Urge your peers to turn their backs on new fracking around the world, as you wisely have in the UK. It’s a high carbon sugar rush and a recipe for political grief. Look at the news from Algeria.

Stop grumbling about renewables. Unlock the opportunities they offer.

Manage a retreat from the carbon frontiers, especially the Arctic. Keep it in the ground.

Press the accelerator on CCS. Use your balance sheet to lever governments into a deal on costs.

It’s easier for an outsider to say what you should stop doing than what you should start. But the more you turn towards a 2°C world, the more you will see its opportunities.

I am urging you to sail into a storm. But you are at your best in storms and the one that will hit you anyway if you delay will be more lethal. In Shell the spectre of Brent Spar hangs over the subject of political risk. Or if it doesn’t it should.

The Risorgimento broke like a wave over Sicily in the middle of the 19th century. It threatened to sweep away the privileges of an inward looking aristocracy convinced that their glory days would never end.

Their struggle to cling to a collapsing system of feudal power is brilliantly portrayed in Lampedusa’s novel The Leopard. A leading character is the worldly and cynical Prince Tancredi, who at one point remarks “Things must change around here if we want things to say the same.”

Wear a mask for change while setting your face against it. It’s a clever ploy and if the stresses aren’t too great – if politics is linear – it can even work.

But when the stresses are existential, it only buys false security. Those who follow the Tancredi strategy get swept away anyway.

You are now in Tancredi’s position. You gave a speech last month that was worldly. Will you now lead your company and your industry towards a choice that is wise?

Yours Sincerely

John Ashton

Martin:

Thanks for directing me here. A transition without transitioning. That is how I came to see the shalegas boom here in the Upper Ohio Valley. The pop-up box I presume wanted me to join and probably contribute funds. Because I have prematurely retired from my profession – because of the non-transition – our financial situation is flimsy, but I will lobby my better half on your behalf.

I am a low-level technician (Professional Land Surveyor) with a lot of not so low level ideas. If I were to prepare a well thought out proposal for using public schools as an instrument of sustainable re-imagination and avenue for alternative non-orthodoxy, might it get an airing here? I could send a brief synopsis for consideration. I have researched enough to know that some of what I would propose is being tried, but none is as ambitious as what I would lay out.

Let me know via e-mail. Thanks again.

Martin: I am a 1st grade teacher and would be very interested in your ‘proposal for using public schools as an instrument of sustainable re-imagination and avenue for alternative non-orthodoxy’. Please, could you share with me? Malcolm.

Thanks for coming over here. Great speech, huh?

No, no, we don’t want your money. We’re just doing what we can do to help, hoping it resonates, and if it does, that the words will spread.

We’d love to publish a thought-piece like that. You actually don’t need to ask – you can post blogs as a member and we can help promote them.

Hi Malcolm. It’s actually Vince’s proposal. I’ll see drop him a line, see if he’s going to post.

Martin

I think everything published made a great deal of sense.

However, think about this, what if you were to create a killer post title?

I mean, I don’t wish to tell you how to run your

blog, but suppose you added something to maybe get folk’s attention?

I mean The best climate change speech you’ll ever read

– /The Rules is kinda plain. You might peek at Yahoo’s front page and note how they create article titles to get people

interested. You might try adding a video or a related

picture or two to get readers excited about what you’ve got to

say. In my opinion, it could bring your website a little livelier.

Thanks for the comment. Yes, good ideas. And we’ll have a look at the Yahoo front page. Cheers.

Thanks for sharing this Martin. A forceful and timely speech. Perhaps even good enough to make me forgive the click-bait title 🙂

Ha! Yeah, old habits die hard. Thanks for being so forgiving 🙂