The article originally appeared on Truthout on March 25, 2015

This week, the World Bank is convening its 16th annual “Conference on Land and Poverty,” which brings together corporations, governments and civil society groups to ostensibly discuss how to “improve land governance.”

As this is happening, hundreds of civil society organizations are denouncing the World Bank’s role in global land grabs. As the organization I am part of, The Rules, is a member of Our Land Our Business, the umbrella campaign of farmer organizations, indigenous groups, trade unions and grassroots organizers from around the world protesting against the Bank’s policies, I often get asked the question, why do civil society and the World Bank have such differing views of the Bank’s role? Reading the Bank’s website, one would think that the World Bank was in the same line of work as the activists challenging their policy. In fact, they have recently adopted the earnest tagline of “Working for a world free of poverty.”

In the grips of ideology

As always, the first place to start is ideology, as it is always a background condition. The World Bank is an unapologetic proponent of neoliberalism, a moral philosophy that pushes self-interest, corporate control and “free markets.” These forces, they believe, will result in such a large amount of overall economic growth that enough will trickle-down to the “masses” to lift them out of poverty.

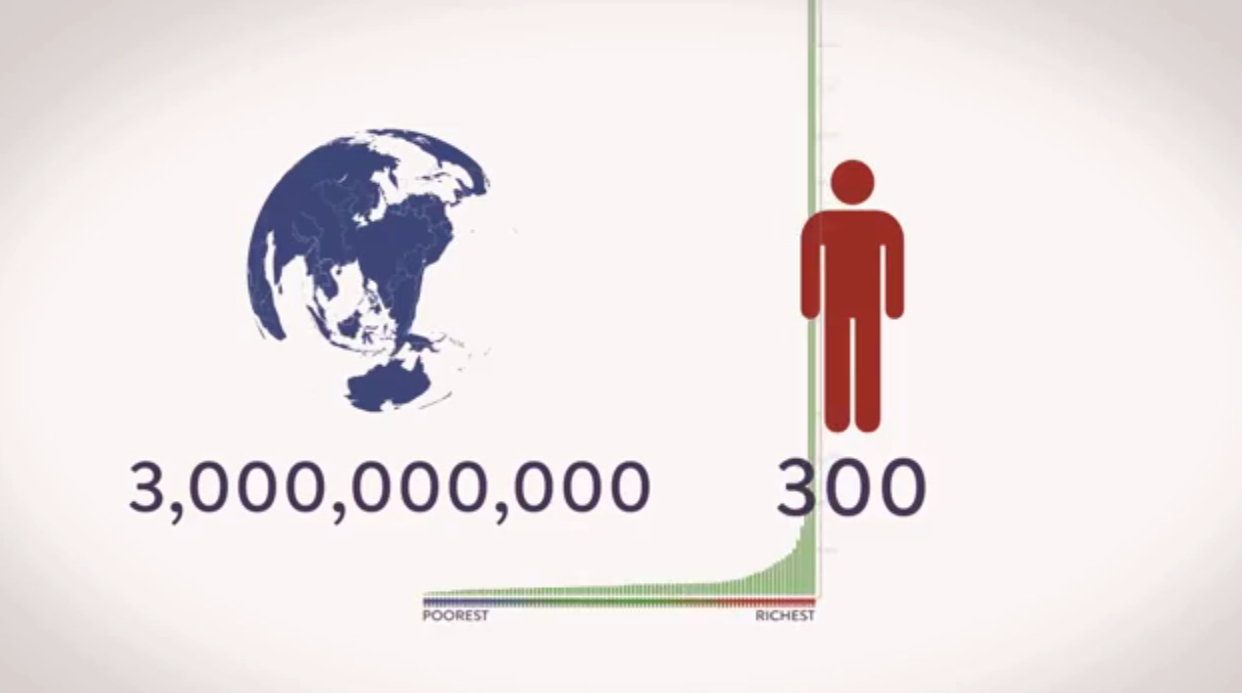

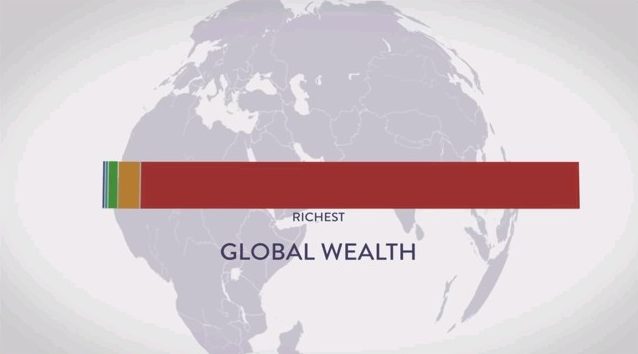

Many have pointed to deep flaws in this logic, including Thomas Piketty, who showed through exhaustive analysis of long-term trends how wealth actually congeals in this system. What’s more, there is ample evidence to show how the self-interest the World Bank believes in, far from ensuring a fair system in which the well-being of all is addressed, actually results in a set of rules that are rigged in favor of a tiny elite. Research from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich has shown that a super entity of just 147 companies controls over 40 percent of corporate wealth. The corporations behind this potent web of power are largely Western corporations, mostly concentrated in the financial sector.

World Bank ideology is deeply linked to the belief that corporate interests and country interests are one in the same. The old US adage of “what’s good for GM is good for America” has expanded through globalization into wholesale neocolonialism through multinational corporations. The recent cable leaks that show how the US State Department exerts influence and strong-arms countries around the world on behalf of the agricultural giant Monsanto is just one example of such egregious policy. (1)

Who’s developing whom?

The two main pillars of the dominant development model are financial aid and foreign direct investment (FDI) to drive economic growth. Each crumbles as a viable strategy under closer inspection.

The dominant story is that rich countries are generous benefactors of poorer countries and that through foreign aid they are offering them a ladder. However, Dr. Jason Hickel of the London School of Economics has shown that when you follow the money, foreign aid is a drop in the ocean compared to the vast flow of money from poor countries to rich. For every $1 of aid that trickles into poor countries, $18 flows out. That means poor countries are loosing about $2 trillion a year due to explicit, pro-corporate policies of rich countries and the World Bank.

We are also told that FDI will lift all boats in the global economy. Indeed, the majority of neoliberal economic policy (in both rich and poor countries as all governments have adopted this logic) is geared toward an increase in FDI. Yet, we know that for every dollar of wealth created since 2008, 93 cents goes to the top 1%. Therefore, by definition, wealth creation creates inequality. So how then could more concentrated wealth solve the problems of the world’s poor?

A related question is how the FDI strategy fares in the face of the natural limits of our planet. Research by David Woodward at the New Economics Foundation shows that the establishment’s strategy for poverty alleviation, best articulated by the Sustainable Development Goals, would require global GDP per capita to rise by more than 12 percent a year until 2030. That would mean global production and consumption would have to increase by a factor of 12, pushing us to a global GDP per capita of more than $100,000.

This is of course absurd. We would need five planets of resources to sustain this type of consumption. Even if this scenario were to play out, it only moves the poorest people above the $1.25-a-day poverty rate, which is way below the $5-a-day rate that is necessary for a standard of living for basic health and well-being, although this says nothing about human dignity or fair distribution of wealth.

Which brings us full circle back to our friends at the World Bank. Given the radical inefficiencies of the global economy, the disastrous path dependency on perpetual material growth, the capital-created destruction of our ecosystem, increasing global instability due to inequality, and the constant state of war and plunder required to prop up the current system, how could anyone advocate for a business-as-usual approach?

Technocracy and the banality of evil

Part of the problem in large institutions like the World Bank, with over 12,000 employees and octopus-like tentacles, is that no one is incentivized to ask these types of questions. In fact, in 2014, as part of the Our Land Our Business core group’s discussions with the Bank, a high-level employee leading one of the country ranking projects, suggested that these types of questions were “above their pay grade.” In other words, even the most senior employees of the World Bank compartmentalize their thinking, allowing them to believe that they are actually helping the world’s poor by simply increasing FDI.

If we look at the history of the World Bank, these command-and-control structures have contributed to generations of World Bank technocrats’ ability to impose life-denying structural adjustment programswithout any accountability or redress for their actions. Not only are they not apologetic for their consequences, intentional or otherwise, but they actually remain smug in their “expertise” and forced imposition of policy. Many believe that these types of policies are the historical relic of an old Bank that has matured and learned from the ills of its past. The Bank’s rebranding belies the fact that it continues to strong-arm countries into pro-corporate, anti-poor, neoliberal policies through new mechanisms such as their Doing Business rankings and the Enabling the Business of Agriculture project, which force countries into a race to the bottom, cutting environmental and social standards, slashing corporate taxes and eliminating trade barriers protecting local industries (a practice rich countries continue to deploy for their own development).

This type of behavior holds deep corollaries with Hannah Arendt’s analysis of the Adolf Eichmann trial in which she coined the term “the banality of evil.” As Judith Butler reminds us, the banality Arendt is referring to is not just how commonplace violence became or how desensitized the perpetrators were to the horrors they inflicted. Rather “what had become banal – and astonishingly so – was the failure to think. Indeed, at one point the failure to think is precisely the name of the crime that Eichmann commits. We might think at first that this is a scandalous way to describe his horrendous crime, but for Arendt the consequence of non-thinking is genocidal, or certainly can be.”

Stated intentions vs. exploitative practices

The implications of the World Bank’s policies cannot be understated. The Oakland Institute, a leading land rights think tank, has documented how local communities around the world face forced evictions and human rights abuses linked to Bank-financed projects. For example, in Uganda, the government evicted 20,000 people for a plantation forest by UK-based New Forests Company, a beneficiary of the International Financial Corporation’s (IFC) funds (the IFC is the World Bank Group’s private sector investment arm).

In 2014, the Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) teamed up with the US Overseas Private Investment Corp. (OPIC), a US government agency, to create a $350 million insurance facility to cover the risks of investments made by the Silverlands Fund, a private equity fund accused of financing land grabs. Essentially, the World Bank and OPIC are using tax payer money to cover the risks associated for a private, land grabbing hedge fund to do business in “emerging markets.”

In Honduras, the IFC financed the palm oil producer Corporación Dinant, accused of assassinations and forced evictions of farmers. Complaints filed against the IFC led to an investigation that found multiple failures in its handling of the loan to Dinant.

These types of “oversights” have been rampant in Bank projects leading to land grabs, the mass displacement of tens of thousands of people, a transition to corporate agriculture and monoculture, further concentration of wealth, and the destruction of local livelihoods and culture in countries as diverse as Mali, Uruguay,Laos, Guatemala, Sri Lanka, Ukraine and the Philippines, just to name a few.

The World Bank’s president, Jim Yong Kim, acknowledged that this trend will remain constant since the Bank will continue to finance development projects such as dams that “always lead to resettlement.”

This is development in the eyes of the World Bank.

Although it is couched in new language such as “public-private partnerships” and “shared value,” the logic remains the same: the privatization of wealth and socialization of loss. As Anuradha Mittal of the Oakland Institute points out, “a Dracula by any other name is still a Dracula.”

Re-localizing power

What’s most troubling about the World Bank’s corporate model of development is that there is a very clear and superior alternative. Even the Bank and UN organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) tout the ability of smallholder farming to fight poverty and bring about sustainable development. Yet their policies enforce the exact opposite outcomes.

We seem to have embarked on the late stages of the banality of evil. First, the technocratic response adds up to little more than denial. In order to further the interests of the systems it serves, it fought smallholder farming until the facts were undeniable. The second is sincerity to the point where many of the bankers believe they are working in the interests of the same people they are harming. This is manifest in the giant banner erected on the side of their DC office that says “End Poverty 2030” or the Bank’s tagline about ending poverty.

The third is persuasive rhetoric, to the point of evangelical fervor. Many of us in civil society have become complicit by believing in the Bank’s stated objectives and even legitimizing the use of their doublespeak.The fourth stage is a doubling down of the pathological behavior – a turning of the screws, if you will. New rankings, new conditionalities, new mandates, more pro-corporate growth. All the while the other states of denial, sincerity and rhetoric reach a fever pitch. There are no contradictions in this behavior; rather they are symptoms of the same psychosis.

So what must be done? Ultimately, this boils down to a question of who has power. Right now, it is centralized to the point of monopoly, and the World Bank’s policy prescriptions shape the future centralization of power even further. However, there are alternatives.

Firstly, developing country governments, progressive foundations and nongovernmental organizations, grassroots organizers and allies of all stripes must focus on the needs of smallholder farmers, who currently produce up to 80 percent of the food and farm 80 percent of the land in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. This would require championing measures to protect existing land users, including anti-eviction laws and recognition of customary systems.

Secondly, we are now realizing the ability for smallholder farmers to significantly help address climate change. In fact, they may be our best bet. According to new research from the Rodale Institute, if instituted universally, regenerative farming techniques, which many smallholders already practice, could offset over global carbon emissions by over 40 percent if scaled on cultivated land. They could offset another 71 percent of emissions if practiced on pastured land. That adds up to over 100 percent of current carbon dioxide emissions.

This could also be the silver bullet against GMOs and industrial agricultural methods. Not only are they hazardous for our health and have no proven yield increases, they are actually contributing to carbon dioxide emissions by creating an opportunity cost to use carbon-reducing and climate-friendly methods of regenerative farming.

These shifts will not be supported by the World Bank, rich country governments and their “development arms” such as DFID and USAID, or the US State Department and their allies at Monsanto. A regenerative economy with distributed wealth and local food security is not in their interests. But then again, the keepers of power have never been incentivized to support progressive reform. There has never been a more important moment to shift power away from corporate oligarchy and their technocratic lieutenants back to the world’s majority. Let us heed Hannah Arendt’s plea to become thinking citizens once again.

Footnote:

1. It is important to note the makeup of the World Bank’s governance structure. Out of the 185 countries that jointly own the Bank, only eight have directors on theBank’s board: the United States, Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, China, Russia and Saudi Arabia. The World Bank’s president is, and always has been, an American.

Leave a Comment