Living in semi-rural Maryland, I joined the book club at my local library to connect with avid readers. Reading some of the books this summer & fall made me understand the role of whiteness in contemporary fiction. These are novels that have nothing to do with race — provided whiteness remains the norm.

To some readers what I have to say will be so painfully obvious that they would not even justify it with a “duh!” Others will need evidence. It is for them — and I was once one of them- that I write the details of my rude awakening to the role of whiteness in contemporary fiction.

What awakened me? An talk by Damali Ayo? A rap heard at a poetry slam? No. Nothing so glamourous. Just a couple of books I read in my book club at the public library.

Look, it’s not as though I haven’t ever before read books with only white characters. But, to quote Justin Trudeau, “it’s 2015.”

What I am reading in the books is more segregating than mere absence of black (or brown or any other colored) characters. In a novel that ostensibly has nothing to do with race relations, a black character is introduced for apparently no other purpose than contrast with all the other characters who are never explicitly said to be white. The introduction of the black character informs (or reminds) the reader that unless otherwise specified, characters are white. Same with the non-white neighbourhood: unless otherwise specified, neighbourhoods are white.

While we may regularly encounter people who remain ignorant of the ways in which whiteness dominates various social and political institutions, to see this dominance spelled out in fictional worlds consciously created by their authors, who remain oblivious to their racism, and to see the resulting novels on bestseller lists, in book clubs and equally oblivious reviews, leads me to despair as to how our society will wake up.

The novels that woke me up (though that was certainly not their intention) are Ruth Reichl’s Delicious! and Sarah Jio’s Goodnight June.

Sarah Jio’s Goodnight, June and Rugth Reichl’s Delicious!

Perhaps (though I doubt it) I just happened upon two unusual examples. Even if that is the case, I want to ask why the authors introduce black characters only to point out their otherness and dismiss them in order to get on with the plot, having asserted whiteness as the norm.

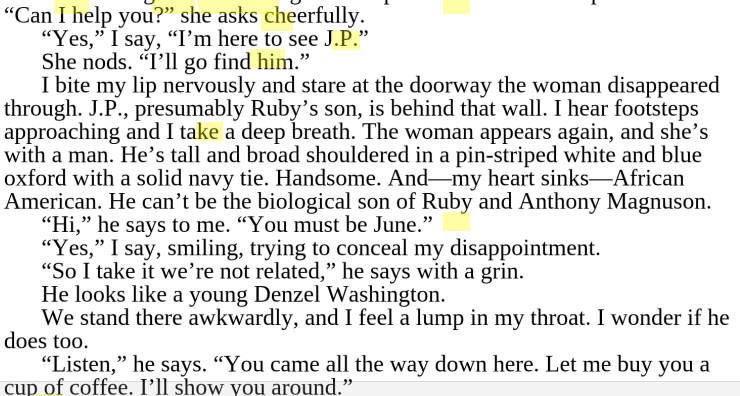

First, June, in Sarah Jio’s Goodnight June. She sets out to search for “J.P.” the son whom her recently deceased great aunt had given up for adoption in his infancy. She arranges to meet someone after corresponding through an online forum. She describes the encounter: “He’s tall and broad shouldered in a pin-striped white and blue oxford with a solid navy tie. Handsome. And — my heart sinks — African American. He can’t be the biological son of Ruby and Anthony Magnuson.”

As a reader, I felt assaulted by the gap in information and the author’s failure to acknowledge it. Were we to assume that Ruby and Anthony were white? This was never stated before this moment, or even clarified after. The narrator never tells us whether she is black or white either. Why is the information that he is African American considered sufficient to conclude that he is the wrong guy? Would it have been so hard to add: “Because they were white.”?? Yes it would because that would violate the assumption that characters are by default white unless otherwise specified.

Secondly, are we really to believe that she observed the color and pinstripes of the man’s shirt before noticing the color of his skin? Or is this there just to let the reader know that she finds him impressive, even though he is black and (therefore) cannot be her long lost cousin.

Who is this black man? We first learn what he is not. This man, simply by virtue of being black is not the man we’re looking for. (He couldn’t be. By the end of the novel we learn that this cousin does not even exist.)

Why did he have to be black? Because this moved the plot along. If he were white, it would have delayed our heroine’s quest, as she would not have been able to rule him out instantly. In order to find the truth, she must first realize that the long lost cousin she seeks does not exist. The appearance of the black man is step one towards confirming this non-existence.

The Black Woman

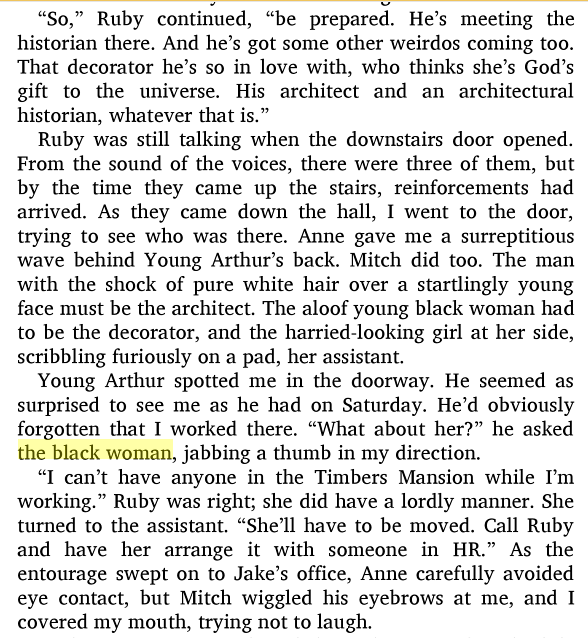

Among dozens of characters in Delicious!, the only character whose skin color is specified is a black woman. She is “the decorator” who has arrived along with the realtor carrying out the sale of Timbers Mansion, home of the magazine which has closed. She represents the change from the old to the new. She appears on precisely one page, just long enough to confirm that she is the only black person among those present in that scene and by extension the entire novel, because that scene establishes that a person is not black unless specified as such.

The one page on which the one black character appears in Ruth Reichl’s Delicious!

A slew of characters are present when the architectural historian and decorator arrive. The decorator is introduced as “the aloof black woman.” In the next paragraph, Arthur, the owner of the house, has the following dialogue, reported thus:

“What about her?” he asked the black woman, jabbing a thumb in my direction.

“I can’t have anyone in the Timbers Mansion while I’m working.”

This reply of the (unnamed) black woman thus ensures that she has no further contact with our heroine and no further role in the story. More importantly, it moves the plot along. Our heroine leaves her job at the dying magazine and moves on to other callings.

After all, race is passé. Lest we doubt the anti-racist credentials of these good people, we may rest assured: as the architectural historian (and our heroine’s love interest) discovers, the mansion in which the magazine operates was once a station on the Underground Railroad. Mission accomplished, the building later came to house a magazine. It is only because the magazine has gone out of business and the house must be sold that its history is unearthed, so securely in the past are such racial conflicts.

“Good people, still, but mostly Asian now.”

By calling the decorator “the black woman” the narrator makes absolutely clear that there is only one black woman here, instantly informing us, without ever using the word “white” that the rest of the characters are, at the very least, not black. Had they been brown or yellow, would we have been told?

Certainly. And if we have any doubt on the matter, we have this paragraph, whose sole purpose seems to be to point out the foreignness of the Asian neighbourhoods within New York.

“I got on the subway and rode all the way out to Flushing, losing myself in a neighborhood so foreign I might have been in Hong Kong or Seoul.”

As Anne Coulter might say, ¡Adios, America!

Never mind that these Asian neighbourhoods have grown there over 2–3 generations, and are as much a part of the fabric of New York as the Lower East Side where she happily takes a tour of foods from all over Europe without once calling them foreign. Stepping into a delicatessen she remarks, “It was like walking into a small Italian village, a kaleidoscope of scent, sound and color …” While the Asian neighborhood feels “foreign,” in the Italian shop she feels drawn in, as accented by the playful imagery of the kaleidoscope. Why the difference? The shopkeeper himself comments on how “the neighborhood’s changed. Good people, still, but mostly Asian now.”

It’s not as if our heroine was averse to Asian food. In fact, we are told, she eats it every night, from an establishment called “Ming’s.” This food is always associated with her lack of home life or social life. We first hear about Ming’s as the place she goes after working late: “… but most nights I pick up take-out from Ming’s, a little place….” In one scene, an older colleague remarks, “But I suppose you will be depending upon Mr. Ming for sustenance. I must confess that I find your reliance upon mediocre Chinese food utterly deplorable!”

In contrast whenever she eats gnocchi, an Italian dish, she is surrounded by people. Her language becomes vivacious: amazing, uncontroll

Is There Class in this Text?

Just as glaring is class. Part of Billie’s job at the magazine is to take calls from readers who have had trouble with the recipes, and send them a refund of the cost of their ingredients. One regular caller, Mrs. Cloverly tends to use inferior substitutes to the gourmet ingredients called for in theDelicious! magazine recipes. Powdered milk in place of heavy cream, canned foods instead of fresh. While talking to Mrs. Cloverly, Billie imagines her kitchen: “It would be small — maybe a double-wide trailer, with one of those half refrigerators and a tiny stove.”

Later, as the last employee left in the mansion, Billie finds herself picking up the phone to call Mrs. Cloverly, and finds it “pathetic” that she wants to talk to “this crazy old lady in a trailer park.”

As it turns out, Mrs. Cloverly faked ineptitude and called the magazine just to escape her loneliness. She actually lives in a mansion and cooks perfectly well.

So does Delicious! have no place for the poor? Not to read it, cook from it, or even, it seems to write for it. Witness the way Billie is pushed to spend money on her appearance.

It is not enough that she has plenty of money. She must also look the part. Billie Breslin, our protagonist, who quit college in California to become a writer in New York, who manages to keep her job even after the magazine closes, who eats out every day even though she knows how to cook, whose rent is covered by her father, has a problem that her friends want her to solve. She dresses poorly and has boring hair. Her colleague takes her to an upscale dress shop and asks the proprietor to give her a “makeover.” The proprietor looks disapprovingly at her current attire, “I’m guessing you buy most of your clothes in thrift shops.” Our heroine sheepishly confesses.

After waiting for Billie to try on various outfits, the colleague asks her to buy them (and to “burn” her old clothes). She says, “But I can’t afford all this!” He calmly advises her to ask her father for an advance from her trust fund. He also urges her to get a haircut, at a salon where this procedure takes three hours.

Her new clothes and haircut are credited with improving her personality, her gait, and the way others treat her. It was not enough to cook and write well. That got her jobs, but not the career of her dreams. To bring her talents together, she had to look epicurean.

Is any message in this book spoken louder than the assertion of class and race? And yet, does anyone notice? Dwight Garner didn’t. Reviewing Ruth Reichl’s Delicious! in the The New York Times, he wrote:

“Food is so complicated a topic, especially elite food. It’s tangled up with class and race and politics and resentment. Little to none of this comes into play in Delicious!”

How mistaken he was.

Why didn’t anyone ever tell me about this book?

Why did I clearly hear the message that Garner missed? Did we read the same book? Are we on the same planet? If I talk about race and class at my book club next week, will anyone believe me?

If I overcame such doubts enough to speak my mind, I must thank Leon.

In Learning all the Time, John Holt writes of a young boy, considered a poor reader, who one day came across a book by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In a meeting that Holt attended, this boy, named Leon, stood up and, voice shaking, demanded to know, “Why didn’t anyone ever tell me about this book?”

What I suppose that Leon had not encountered till then were books in which his life experience, the very idea of his existence, was validated. Books that did not alienate him with their unspoken assumptions, so unspoken that there was no way to speak against them, no way to talk back, no way to break the silence, because the silence remained unheard, the invisibility unseen. And no means of resistance other than being a “poor reader.”

Finally having found a book that gave voice to his experiences, that rendered him visible and recognized the sense of erasure and invisibility that permeated all the other texts that had passed for literature in his readings thus far, he felt alive, engaged, enraged — he felt like reading.

And he expressed this feeling in a question, “Why didn’t anyone ever tell me about this book?”

Here is the passage from Learning All the Time:

Leon, a young black man of about seventeen whom I met some years ago in an eastern city, was a student in an Upward Bound summer programme. He was at the absolute bottom of all his regular school classes, tested, judged, and officially labeled as being almost illiterate. At the meeting I was part of, the students, some black, some white, all poor, had been invited to talk to their summer-school teachers about what they could remember of their own school experiences and how they felt about them. Until quite late in the evening Leon didn’t speak. When he did, he didn’t say much. But what he said I will never forget. He stood up, holding before him a paperback copy of Dr. Martin Luther King’s book Why We Can’t Wait, which he had read or mostly read, during that summer session. He turned from one to another of the adults, holding the book before each of us and shaking it for emphasis, and, in a voice trembling with anger, said several times at the top of his lungs, “Why didn’t anyone ever tell me about this book? Why didn’t anyone ever tell me about this book?” What he meant, of course, was that in all his years of schooling no one had ever asked him to read, or ever shown him or mentioned to him, even one book that he had any reason to feel might be worth reading.

It’s worth noting that Why We Can’t Wait is full of long intricate sentences and big words. It would not have been easy reading for more than a handful of students in Leon’s or any other high school. But Leon, whose standardized Reading Achievement Test scores “proved” that he had the reading skills of a second-grader, had struggled and fought his way through that book in perhaps a month or so. The moral of the story is twofold: that young people want, need, and like to read books that have meaning for them, and that when such books are put within easy reach they will sooner or later figure out, without being taught and with only minimal outside help, how to read them.

from John Holt, Learning all the Time

Show your customers that your small business is built upon the hard work and dedication of your employees. These can be used directly in your office, when you are at business meetings, or even as tradeshow giveaways. Using hashtags can expand the reach of your tweets far beyond the wall of those who follow you.