Moving beyond clicktivism

Most of you reading this have probably received numerous emails asking you to sign petitions on various causes over the years, some of them will have even come from us at /The Rules. If you are anything like me the vast majority of them will remain unread, and the cumulative effect of this can be demoralising. Critics of this type of activism often refer to it as “clicktivism”, and they argue that it can distract attention from less glamorous but effective on ground activism.

This is not to say that online petitions don’t serve a purpose, nor that they haven’t helped to bring about changes, or that liking a post on Facebook or Retweeting something on Twitter are empty gestures. These activities can be very powerful for raising awareness, and can be an important first step to engage people with an issue they may not have otherwise known about.

However at the kind of systemic change that we are seeking to bring about at /The Rules needs something more, it’s about being in for the long-haul, and so we have been thinking long and hard about how to use these digital tools to better facilitate the kind of change we want to see in the world.

This year we’re going to be rolling out a new suite of community focused tools designed to help our members work with us and with each other to make the long term changes that the world so needs right now.

What’s right with online activism?

Online petitions are undeniably popular, the run your own petition platform Change.org has over 70 million users in 196 countries, while the global online movement Avaaz has more than 40 million people who have signed their petitions. With numbers like these pressure can be brought to bear at key points in a campaign when public support is needed. These tens of millions of people can be made aware of issues that the mainstream media would not cover, and given simple steps they can take to act on them.

Many of these people have gone on to get more involved, starting local groups or volunteering for organisations that work directly on the issue. There are also many instances where a petition is the right tool for the job, especially for single issues at a local level. If you want to see some examples you can check out the Change.org and Avaaz.org websites for yourself.

What’s wrong with online activism?

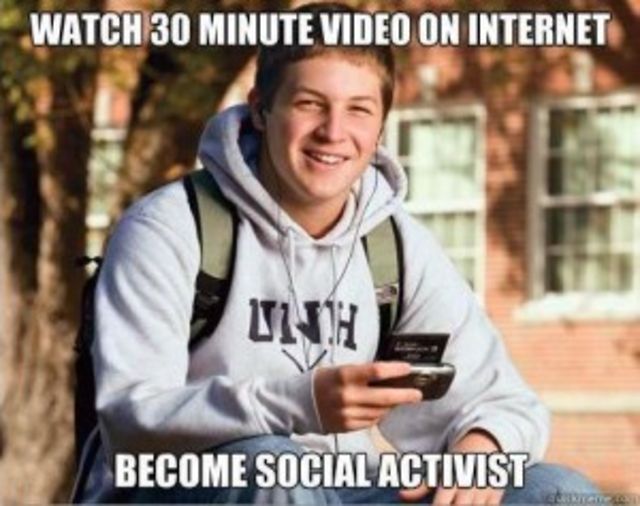

Watch 30 minute video on Internet. Become social activist

Very often online petitions are simply the wrong tool for the job. A petition is not going to stop climate change or end violence against women. They may be useful tools at key moments where policy changes are required, but often they are vague and leave people thinking that they have wasted their time by signing, making them pessimistic about the possibility of achieving a change.

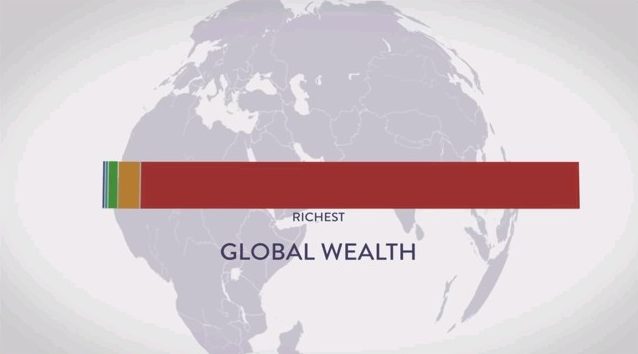

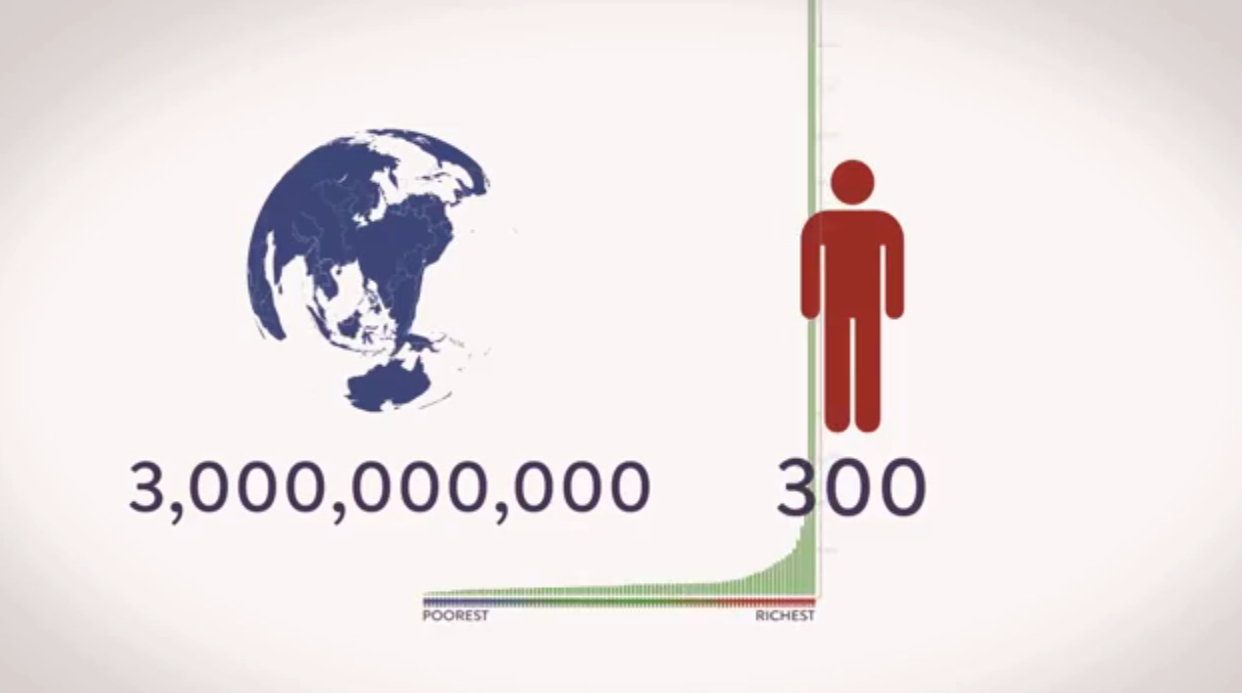

At /The Rules we believe that many of the biggest challenges facing us today, such as climate change, global inequality, the persistence of poverty in a world of plenty, are systemic and cannot be dealt with one by one, but require a total change to the system – we’ve outlined many of the facets of that system in our One Party Planet pamphlet – these kind of problems are not going to be solved by a petition no matter how many people sign it.

What is clicktivism?

Clicktivism is generally a pejorative term used to describe online activism where clicking a link replaces any real action, and the clicktivist thinks they have done their bit while not really having contributed anything. Another term for this is slacktivism – activism for slackers.

The rise of the slacktivist

Micah White of AdBusters wrote a searing critique of clicktivism in which he laments that:

“Gone is faith in the power of ideas, or the poetry of deeds, to enact social change. Instead, subject lines are A/B tested and messages vetted for widest appeal. Most tragically of all, to inflate participation rates, these organisations increasingly ask less and less of their members. The end result is the degradation of activism into a series of petition drives that capitalise on current events. Political engagement becomes a matter of clicking a few links. In promoting the illusion that surfing the web can change the world, clicktivism is to activism as McDonalds is to a slow-cooked meal. It may look like food, but the life-giving nutrients are long gone.”

I’m not in 100% agreement with what he writes, as with any tool there are times when it is appropriate and others when it is not, but much of the sentiment rings true.

Why then do so many organisations encourage clicktivism?

As mentioned above there are plenty of examples of where it works for specific issues, and who wouldn’t want a membership of millions. There is also a relentless pressure to move with the times, so those first successes end up being copied, and not always well. There is also another dynamic at play where organisations become dependant on the leads that clicktivism generates to raise more funds, until we end up in the situation where we are today with people’s inboxes being flooded with petition requests from a huge number of organisations and a growing scepticism about the claims they make.

Stop online petitions forever!

What is the alternative?

So if clicktivism doesn’t work for the kind of change that we need to see in the world and with the NSA watching everything that happens online, is it time to just pack up the Internet and go home?

There is much serious criticism of clicktivism, prominently Malcolm Gladwell writing on what he saw as the failings of slacktivism in 2010, by comparing it to the kind of activism that won out in the civil rights movement where strong ties that are developed in person seemed to be what held the activists together for the long struggle they were involved in, as opposed to the weak ties that develop online.

“What makes people capable of this kind of activism? The Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam compared the Freedom Summer dropouts with the participants who stayed, and discovered that the key difference wasn’t, as might be expected, ideological fervor. “All of the applicants—participants and withdrawals alike—emerge as highly committed, articulate supporters of the goals and values of the summer program,” he concluded. What mattered more was an applicant’s degree of personal connection to the civil-rights movement. All the volunteers were required to provide a list of personal contacts—the people they wanted kept apprised of their activities—and participants were far more likely than dropouts to have close friends who were also going to Mississippi. High-risk activism, McAdam concluded, is a “strong-tie” phenomenon.”

However in 2011 the world saw a new phenomenon of activists using online tools to coordinate the overthrow of governments across the Arab world. Decentralised networks proved effective for staying one step ahead of the authorities, and the power to communicate outside of official channels spread the word to many more people. Not that social media was necessary for the Arab Spring to happen, but it certainly helped.

Last year I had the privilege to go and meet activists involved in the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul. I visited their apartment which served as a makeshift first aid centre and media centre during the protests, and these dual purposes mirror what was necessary to build the momentum of the protest until it became about more than saving trees in an inner city park and mobilised millions of people onto the streets to question the direction in which the country was heading.

The first aid centre was necessary because people were literally putting themselves in the firing line – gas masks still hung from coat rails on the backs of doors, and first aid kits sat on shelves. Without people willing to take that risk none of it would have happened.

However the activists themselves were very clear that without social media they never would have reached critical mass. As the protests grew and police brutality spiralled out of control the mainstream media said nothing as the government tried to stifle the news – CNN in Turkey broadcast a documentary on penguins. Meanwhile the media centre was providing 24 hour coverage through social media to millions of people across Turkey and around the world. People in the midst of the protests were Googling how to deal with tear gas and then streaming what was going on around them live to the world.

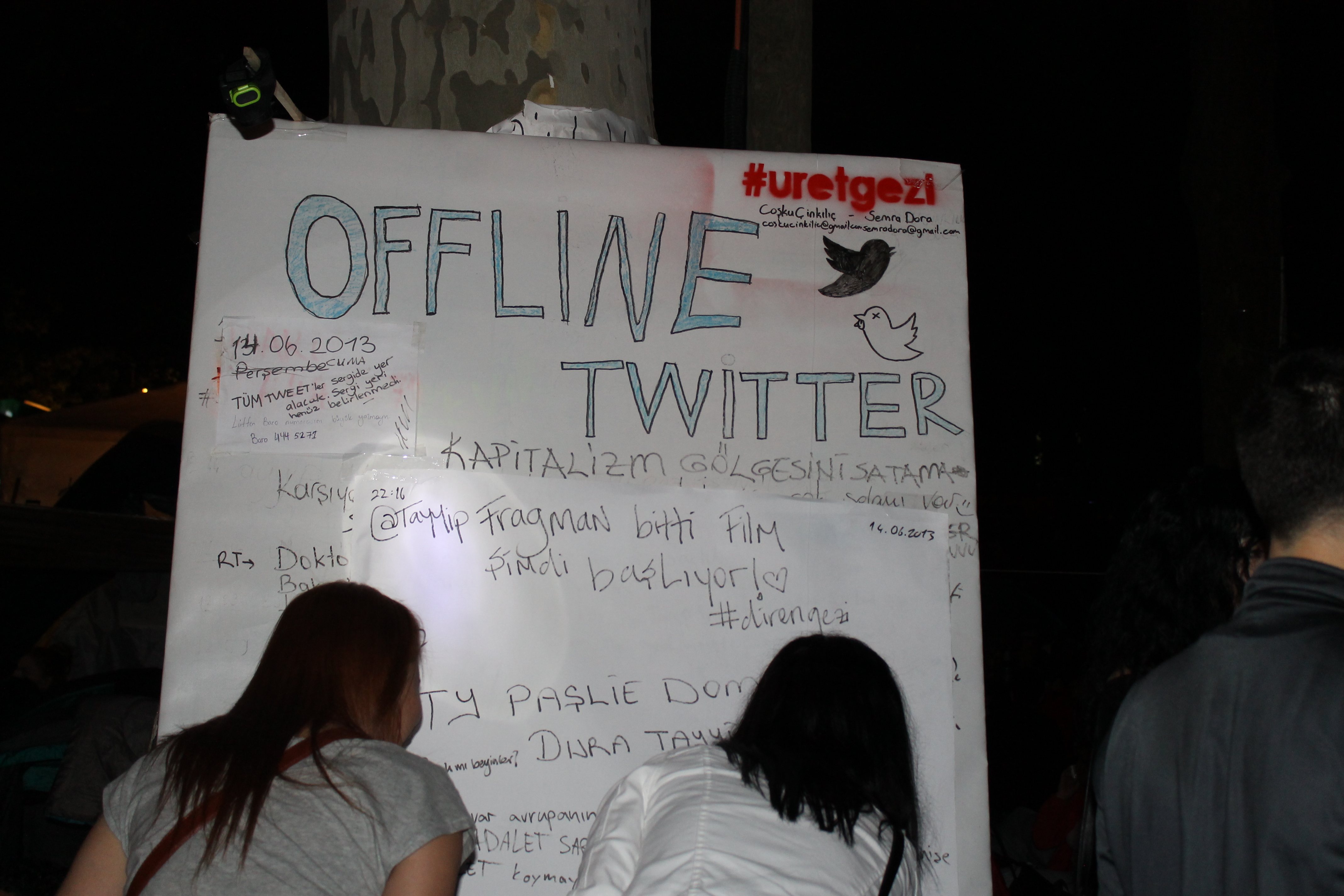

Offline Twitter wall in Gezi Park

Even Gladwell thinks that the weak ties developed online can be generally positive and help massively in the spreading of information:

“There is strength in weak ties, as the sociologist Mark Granovetter has observed. Our acquaintances—not our friends—are our greatest source of new ideas and information. The Internet lets us exploit the power of these kinds of distant connections with marvellous efficiency. It’s terrific at the diffusion of innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration,”

The question we are wrestling with is how do we use the power of weak ties for spreading ideas, at the same time as developing the strong ties that are necessary between activists online? To encourage deeper engagement with our community we need to see them as partners and not just list members.

If our aim is to bring radical thought to the mainstream we are fighting a massive battle, both against the mainstream media and against the $500 billion spent on advertising each year telling people that the only way to be fulfilled is to consume. We simply cannot do this on our own.

Together we can though. Who is in our community? Writers, film-makers, lawyers, programmers, hackers, designers, disillusioned marketers and ad executives. Couldn’t we be doing something more than asking you to click a button and sign a petition?

Cognitive surplus

Writer Clay Shirky coined the idea of Cognitive Surplus, that people are increasingly spending their time creating rather than consuming media, and that this impulse can be put to good use. You can see him explain in his TED Talk.

How can we tap into that same dynamic that makes Wikipedia successful, or powers the OpenSource movement with projects such as WordPress – free software used to power a quarter of the world’s top 10 million websites, and the free, volunteer-developed operating system Linux that now runs the majority of the world’s web servers? The success of these examples lies in providing intrinsic rewards. the reward of a job well done rather than a job well paid.

Can we build a community where people can put their talents to work in bringing radical thought to the mainstream? A community that recognises and celebrates those who contribute to this movement.

Conclusion

Online petitions still have their place, and we will continue to use them where appropriate, but we’re trying to build something deeper and more sustainable that moves beyond mere clicktivism.

To do this we have launched our community section where people are encouraged to work together and form their own activist networks to bring radical thought to the mainstream by creating engaging content, highlighting issues that are neglected and pushing this out through their social networks.

We’ll be learning as we go along, but we hope that you’ll join us for the journey.

we could create a scale of engagement, of increasing levels of commitment in action, to provide a pathway toward powerful engagement with honored places to be at each step and confrontable steps upward.

Hi Bruce,

You are describing the so-called “ladder of engagement.” This is one of the most flawed paradigms of activism and has been used to justify clicktivism for years.

Micah

micahmwhite.com

Hey Bruce that’s the kind of idea behind what we’re doing. Although we want to avoid making it too hierarchical.

Hey, you quoted from my article but you spelled my name wrong.

here’s the full article:

A battle is raging for the soul of activism. It is a struggle between digital activists, who have adopted the logic of the marketplace, and those organisers who vehemently oppose the marketisation of social change. At stake is the possibility of an emancipatory revolution in our lifetimes

The conflict can be traced back to 1997 when a quirky Berkeley, California-based software company known for its iconic flying toaster screensaver was purchased for $13.8m (£8.8m). The sale financially liberated the founders, a left-leaning husband-and-wife team. He was a computer programmer, she a vice-president of marketing. And a year later they founded an online political organisation known as MoveOn. Novel for its combination of the ideology of marketing with the skills of computer programming, MoveOn is a major centre-leftist pro-Democrat force in the US. It has since been heralded as the model for 21st-century activism.

The trouble is that this model of activism uncritically embraces the ideology of marketing. It accepts that the tactics of advertising and market research used to sell toilet paper can also build social movements. This manifests itself in an inordinate faith in the power of metrics to quantify success. Thus, everything digital activists do is meticulously monitored and analysed. The obsession with tracking clicks turns digital activism into clicktivism.

Clicktivists utilise sophisticated email marketing software that brags of its “extensive tracking” including “opens, clicks, actions, sign-ups, unsubscribes, bounces and referrals, in total and by source”. And clicktivists equate political power with raising these “open-rate” and “click-rate” percentages, which are so dismally low that they are kept secret. The exclusive emphasis on metrics results in a race to the bottom of political engagement.

Gone is faith in the power of ideas, or the poetry of deeds, to enact social change. Instead, subject lines are A/B tested and messages vetted for widest appeal. Most tragically of all, to inflate participation rates, these organisations increasingly ask less and less of their members. The end result is the degradation of activism into a series of petition drives that capitalise on current events. Political engagement becomes a matter of clicking a few links. In promoting the illusion that surfing the web can change the world, clicktivism is to activism as McDonalds is to a slow-cooked meal. It may look like food, but the life-giving nutrients are long gone.

Exchanging the substance of activism for reformist platitudes that do well in market tests, clicktivists damage every genuine political movement they touch. In expanding their tactics into formerly untrammelled political scenes and niche identities, they unfairly compete with legitimate local organisations who represent an authentic voice of their communities. They are the Wal-Mart of activism: leveraging economies of scale, they colonise emergent political identities and silence underfunded radical voices.

Digital activists hide behind gloried stories of viral campaigns and inflated figures of how many millions signed their petition in 24 hours. Masters of branding, their beautiful websites paint a dazzling self-portrait. But, it is largely a marketing deception. While these organisations are staffed by well-meaning individuals who sincerely believe they are doing good, a bit of self-criticism is sorely needed from their leaders.

The truth is that as the novelty of online activism wears off, millions of formerly socially engaged individuals who trusted digital organisations are coming away believing in the impotence of all forms of activism. Even leading Bay Area clicktivist organisations are finding it increasingly difficult to motivate their members to any action whatsoever. The insider truth is that the vast majority, between 80% to 90%, of so-called members rarely even open campaign emails. Clicktivists are to blame for alienating a generation of would-be activists with their ineffectual campaigns that resemble marketing.

The collapsing distinction between marketing and activism is revealed in the cautionary tale of TckTckTck, a purported climate change organisation with 17 million members. Widely hailed as an innovator of digital activism, TckTckTck is a project of Havas Worldwide, the world’s sixth-largest advertising company. A corporation that uses advertising to foment ecologically unsustainable overconsumption, Havas bears significant responsibility for the climate change TckTckTck decries.

As the folly of digital activism becomes widely acknowledged, innovators will attempt to recast the same mix of marketing and technology in new forms. They will offer phone-based, alternate reality and augmented reality alternatives. However, any activism that uncritically accepts the marketisation of social change must be rejected. Digital activism is a danger to the left. Its ineffectual marketing campaigns spread political cynicism and draw attention away from genuinely radical movements. Political passivity is the end result of replacing salient political critique with the logic of advertising.

Against the progressive technocracy of clicktivism, a new breed of activists will arise. In place of measurements and focus groups will be a return to the very thing that marketers most fear: the passionate, ideological and total critique of consumer society. Resuscitating the emancipatory project the left was once known for, these activists will attack the deadening commercialisation of life. And, uniting a global population against the megacorporations who unduly influence our democracies, they will jettison the consumerist ideology of marketing that has for too long constrained the possibility of social revolution.

— Micah White, PhD is the American creator of the Occupy Wall Street meme, the co-founder of Boutique Activist Consultancy and the author of THE END OF PROTEST (forthcoming from Knopf Canada).

This article was originally published at The Guardian.

Hey James,

I really enjoyed reading this article and the replies to it. It has a good balance. When I received my first e mails with requests for signing petitions I was kind of entusiasthic. It is a very powerful tool to create pressure at key moments as you said. But when I read about the business model behind those platforms I doubted their credibility and I was disappointed. I think governments and companies barely felt under pressure in the past exept when the tides of outrage went high enough that people get on the streets to protest (and they don’t do so every day). So most of the time they were able to ignore protests and critics from a few activists as they had the impression that the broad public isn’t aware of whats going on or doesn’t care about. And individuals firm that public get the same impression. You hear something gross going on from the news but you don’t see anyone spending any attention on it – so whats the deal? You have to earn money for yor daily bread. But those online petitions are changing this. You get more informations than from the 10 second comment in the news, you see that there are a lot of people that are also not ok with whats going on and that this mass of people can’t be overlooked or ignored by those in charge. Some people seem to think that real activists have to go on the street and raising signs at protest marches. Think that is fine if you live in New York, San Francisco or even Frankfurt, but if you live in an rural area you would be the only one on the street and protests only have any use if you get any attention by the media. Otherwise you are just a stange dude with a sign. Unless it is a real important issue you neighter will see me buying a train ticket to go to a protest hundreds of miles away nor buying an ticket for at least 500$ to join some sort of activist community meeting in New York, Melbourne or Johannesburg. Thanks to the internet thats not so bad. I can read and write articles, share thoughts with others and add my abilities to the community to help in my way. As you call yourself activists maybe change the names of those people who are just signing online petitions into passivists. Many people will never become activists for vearious reasons. Don’t blame them for. If they add presure on your demands by simply signing your online petitions that is a lot. And don’t forget that you likely create awareness with these people for all the problems you have to fight and that solving them will not be for free. People who are aware of what is going on may not stand in your way if changes might be sometimes uncomfortable

Why is there so much emphasis nowadays on signing petitions online? What happened to paper petitions? Despite Royal Mail coming later in the day now, I still like to send things through the post. Not everyone has a computer, or can afford one! Thanks for sharing this petition!

Just desire to say your article is as amazing. The clarity in your post is simply excellent and i can assume you’re an expert on this

subject. Well with your permission let me to grab your

RSS feed to keep updated with forthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please continue the gratifying work.

trump’snarcissistic ways are not making america great again there making america hate again.