How to Change The System

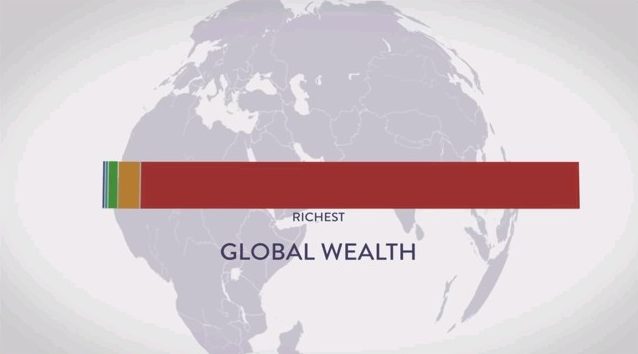

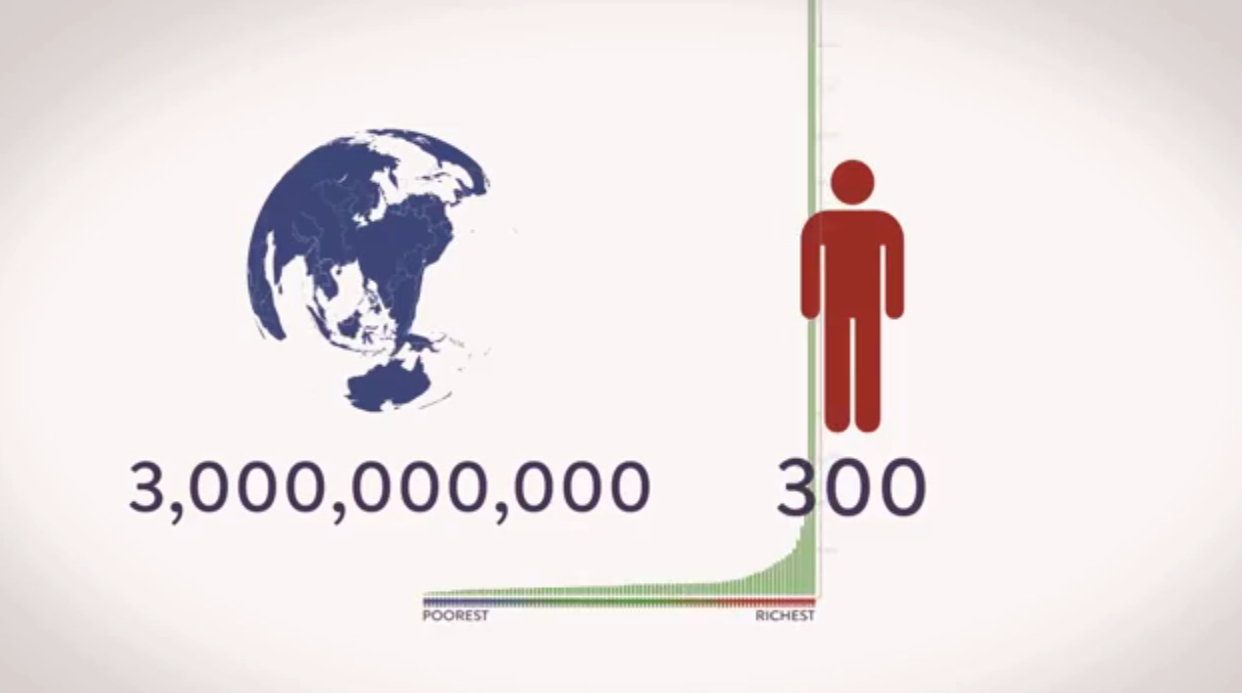

It’s untrue, unhelpful and intellectually lazy to suggest that the 0.01% are bad people. No one planned it and no one is to blame. This is not a binary, satisfying battle between good and evil.

Yes, I’m saying the Davos set have this elaborate plan, and I’m readily name-checking high-profile powerbrokers but I nonetheless do not believe that they are entirely accountable. Collectively, the 0.01% may be doing nothing to meaningful to challenge the status quo and pretty much everything they can think of to profit from it, but that’s not the same as being its architects. It’s not even the same as being wholly intentional in perpetuating it. To put it very simply, what existed before any of today’s lot were in power fostered the causes for the conditions today, within which people with their resources (be they intellectual, educational, physical and/or financial) and characteristics can thrive. Without the causes and conditions, the thriving cannot happen; with them in place, those who naturally align with the motives and drivers of the system will inevitably rise to the top and hence perpetuate it. And it rolls back thus through time.

What we are really seeing is a stage in the evolution of a complex adaptive system. The forces inherent within it are orders of magnitude more powerful than any group or corporation or state. The current set-up is largely the result of human decision making, for sure, but to try and pick the decisions apart and attribute blame to any individual or grouping in power today is to misunderstand the nature of complex systems. The most the 0.01% can do is ride the waves, quash or divert any significant mutations of resistance, and maybe, occasionally, affect the direction of the evolution by a degree or two.

For anyone to truly shake things up, they would need to alter the logic of the system itself. They would need to change its pattern, what, in systems theory, is called its attractor, which includes changing the incentives and drivers pulling it along. System and complexity theorists talk about ‘bifurcation points’–a point of instability at which the system can change abruptly and new forms of order suddenly appear. This is what we need to be looking and fighting for. Which leads to a quick word of caution on traditional approaches to ‘policy’.

We have a very strong and dominant paradigm for what good policy analysis is, and what sort of policy change it leads to. Pick up any report from a political party, think tank or NGO and you will see a list of recommendations for legislative or public policy changes they want to see implemented. It will, in almost all cases, be made up of a data set, a ‘common sense’ analysis of the environment, and what seems a reasonable menu of practical steps. These may be perfectly logical when taken in isolation but they tend to emerge from people who have been trained to view the world—as we all have—as a Cartesian machine, in which change is linear and one thing follows inevitably and predictably from the last, rather than people trained to see it as a system—that is, with non-linear feedback patterns, attractors, self-organising properties and the like. Because it is still a new science (the first theories were postulated back in the early 20th century but it really only started to be studied in serious scientific arenas in the 1970s) very little if any of the powerful lessons of systems thinking have made it into places where public policy is studied, and even less into the corridors of power. But we should recognise this and take it upon ourselves to learn, rather than wait for it to gradually seep into the walls around us. The potential we could unleash if we do so is truly staggering

This blog is an extract from The One Party Planet. You can read the complete version here: https://www.therulesblog.wpengine.com/en/actions/one-party-planet-join-page

Leave a Comment