Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) is like Green Growth, Inclusive Growth, Green Economy and so many other catch-all and concepts which are too vague and broad to be useful: nice labels put on ‘business as usual’ policies avoiding the radical changes that are required.

Climate-Smart Agriculture is just another vain attempt for decision makers and business interests to alter the world by trying to force it to conform to their vision, ideology or business model. They blindly hope they can change it by doing more of the same or through slight adjustments, following the well known motto that “the crises we are facing are due to a lack of implementation of past and failed policies”. In other words, if austerity, (free) trade liberalization, growth-led development and the Green Revolution failed, the basic logic is never questioned, only how, and how, hard, it is implemented.

Given that our societies might well be on the edge of collapsing, this denial acts like a weapon of mass destruction. And unfortunately, it is all too common in the field of food and agriculture.

First introduced by the FAO in 2010, the concept of Climate-Smart Agriculture quickly found a champion in the Global Alliance for Climate Smart Agriculture (GACSA). Launched in September 2014, its objective is to spread the CSA creed in as many international fora as possible.

According to the FAO, “Climate-smart agriculture promotes production systems that sustainably increase productivity, resilience (adaptation), reduces/removes GHGs [Green House Gases] (mitigation), and enhances achievement of national food security and development goals”. Although it might sound promising, there are serious problems. For a start, there is no clear definition of what is and is not ‘smart’. There are no social or environmental safeguards. And, perhaps most tellingly of all, there is no accountability to ensure that all the FAO’s grand promises are actually honoured. In fact, members of the GACSA have said explicitly that “accountability is too strong a word”(1).

This lack of clarity and accountability leaves room for a multitude of sins. For example, the CGIAR [the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research] – which was part of the partnership established by the FAO to coordinate action on CSA while the concept had just being created –, member of the GACSA and represented in it through five of its institutes, actually promotes herbicide tolerant crops (such as the Round-Up ready crops from Monsanto) as a climate smart agriculture “success story” (2).

It is these critical contradictions and weaknesses in the core concept that have led CIDSE, the organisation I work for, to say that CSA seriously risks “leading to green-washing of undesirable agricultural production models which aim at perpetuating an inefficient and unjust food system while supporting the further commodification and financialization of agriculture” (3). And why today, more than 350 organisations from all over the world – including Via Campesina (the world’s largest peasant farmers’ movement), Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, Slow Food and many others – are raising their voices to say NO to Climate-Smart Agriculture and its Global Alliance (see the whole statement here).

This is all part of a larger trend. In recent years, as climate change, inequality and poverty have become more central in the political landscape, they have generated something of a soft consensus, in which everyone is part of the solution and from which everybody has something to gain. Because growth is seen as the solution to everything, and investors and multinational companies remain the main drivers of growth, the private sector is now a key player in shaping international policies dedicated to facing societal challenges.

Entire global political initiatives are constructed to promote these agendas, mostly at the behest of large multinational agribusinesses and their champions. A few years ago, the G8 New Alliance for Food security and Nutrition was established to promote the industrial agriculture in Africa, under the guise of it constituting a “Green Revolution”. Despite the fact their model relies heavily on the use of synthetic fertilisers, industrial meat production and large-scale industrial agriculture – which are all widely recognised as contributing to climate change and undermining the resilience of farming systems – multinational agribusinesses have also now Climate-Smart Agriculture.

Today, agribusiness corporations that promote all of these can and do call themselves “Climate Smart” (4). Indeed, Monsanto, Yara, Wal-Mart and McDonald’s have either joined the alliance, and are referring to the concept of CSA and have even started their own ‘climate-smart’ programs. Perhaps they deserve an award: if the tobacco industry were to manage to sell its cigarettes as medicine against cancer we would definitely give them an award. But let’s not fool ourselves: not only are they hiding their current practices and models behind a green CSA façade, they are actively using the climate, hunger and the economic crisis as an opportunity to expand their operations. A ‘shock doctrine’, as Naomi Klein would put it, further endangering our planet and our future.

Believing that we can make our world and our societies safe with marginal modifications to the ‘growth and profit at all costs’ model, without addressing the central contradiction of infinite growth on a finite planet is now the major fallacy of our times. The truth is, we have everything to lose from the idealistic belief that every country, every company, every person can grow their material wealth without destroying the climate.

We must wake up from this fantasy. Pursuing the development of “solutions” that do not address the underlying causes of poverty, hunger, inequalities and climate change, or take into account the limits of our planet is a waste of time, money and energy. As Samuel Alexander puts it: “if our civilisation does not embrace an ethics of sufficiency – and if we persist in the fantasy of globalising affluence and hoping technology and ‘free markets’ will solve our social and ecological problems (…) before this century is out, our civilisation will have collapsed; will have consumed itself to death” (Prosperous Descent, p. xiii).

When it comes to climate change alone, the change needed is as deep as it is urgent. Whether or not we believe in ‘peak oil’, global warming requires a radical shift in how we understand and react to the fact that 80% of the confirmed fossil fuel reserves must stay in the ground if we want to stay below a 2°C increase (5).

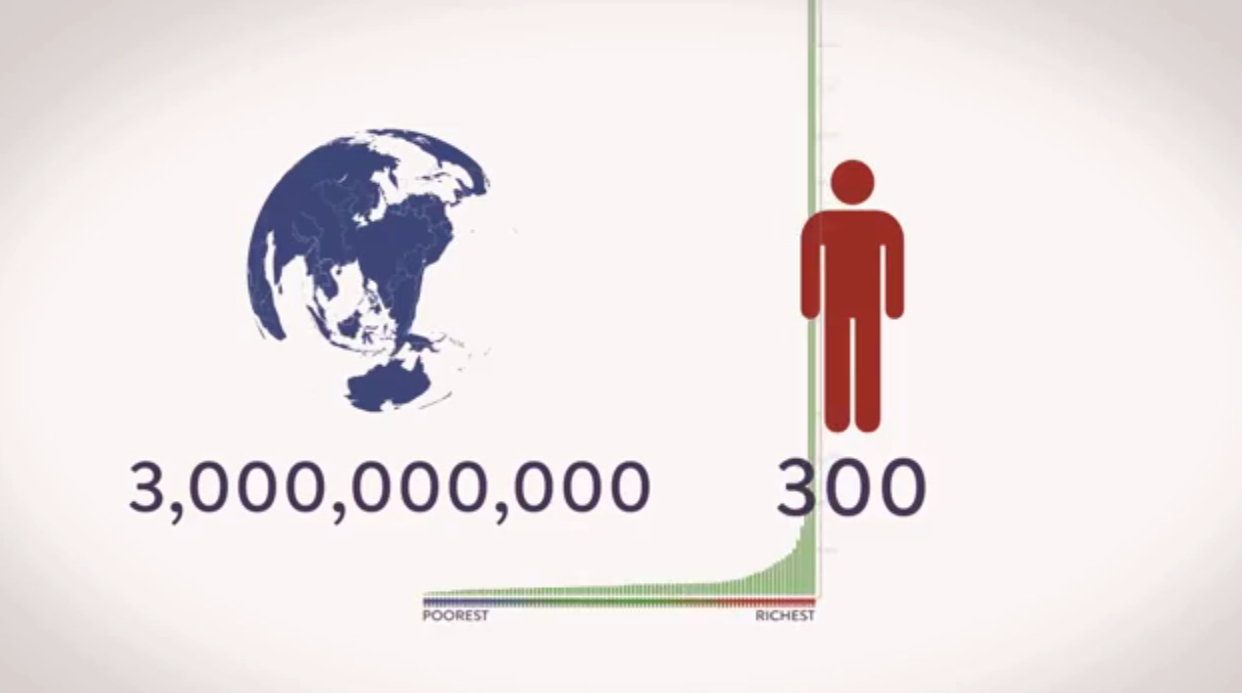

How can we overcome this impasse? By moving away from fossil fuels in a planned and equitable way; this is what the concept of degrowth stands for. Indeed, degrowth is a phase of planned and equitable contraction of resource and energy demand in the richest nations (6), in order to achieve an economy that operates in a steady state, within Earth’s biophysical limits (7). Put another way, to live in a state of frugal abundance.

For food systems, this means that we cannot keep thinking about “developing” them the way we currently do, through export-led policies which are favouring concentration and industrialisation. Or through focussing on increasing international trade, improving yields through chemical and fossil-fuel based inputs. We need to think about re-designing the whole food system because in (soon to be) “developed” countries, “emissions resulting from activities beyond the farm gate account for approximately half of the food chain’s emissions” (8). And we must factor in the gross inequalities, the impoverishment and the health issues that are linked to our current system.

As suggested in the statement “Don’t be fooled! Civil Society says No to ‘Climate Smart Agriculture’and urges decision makers to support agroecology”, such changes require “a radical transformation of our food systems away from an industrial model and its false solutions, and toward food sovereignty, local food systems and integral agrarian reform in order to achieve the full realization of the human right to adequate food and nutrition”.

When it comes to agricultural production, Agroecology offers a clear and ready approach for achieving frugal abundance. In addition to being knowledge (9) and labour intensive, highly productive (10) and restoring soils, Agroecology decreases the resources and fossil-fuel energy needed to produce food, thereby contributing to the transition towards a truly sustainable society. Moreover, with initiatives in participatory democracy (e.g. food policy councils), relocalisation, the development of short food supply chains, solidarity-based economic initiatives (e.g. Community Supported Agriculture (11), farmers’ markets, urban agriculture, rural-urban linkages, food hubs), and the resilience that comes with increased autonomy at various levels (e.g. seed sovereignty), plenty of alternatives exist to help transform the food system form the bottom up.

As, “the agro-food system is both a symptom and a symbol of how we organize ourselves and our societies” (Tim Lang), the alternatives being developed within it are also a symbol of how we could organise our societies. Decision makers need to acknowledge this broad range of tangible and concrete options, to listen to and support those who are developing them, rather than side with global top-down initiatives that rely on models from the past.

All of us, individually and together, can also do our part by supporting progressive initiatives wherever we find them. This is the only way we will succeed in loosening the grip on power by large corporate interests that are, right now, preventing the full-scale development of radically new lifestyles and ways of organising our society. This is the only way we will move towards the promises of frugal abundance.

Today, more than 350 organisations from all over the world stand against Climate Smart Agriculture. They are at the heart of a call for radical change for people and planet and they will not be fooled by the illusion of change offered by CSA. They are united in their call for agroecology “to be endorsed as the mainstream pillar of agricultural policy frameworks worldwide”.

This is the way forward.

François Delvaux,

Policy officer at CIDSE

NB: this paper presents the perspective of its author and does not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of all the signatories of the statement

If you want to know more about climate-smart agriculture, CIDSE has published one discussion paper and one briefing on the topic:

• http://www.cidse.org/publications/just-food/food-and-climate/csa-the-emperor-s-new-clothes.html (October 2014)

• http://www.cidse.org/publications/just-food/food-and-climate/climate-smart-revolution-or-a-new-era-of-green-washing-2.html (May 2015)

You’ll also find more information about the civil society statements and other resources on climate smart agriculture on the following website: http://www.climatesmartagconcerns.info

Notes:

(1) as is reported in“GACSA: report of the first working meeting” (2014), page 11: http://www.fao.org/3/a-au671e.pdf

(2) CGIAR, “Climate-smart agriculture success stories from farming communities around the world” (2013) https://ccafs.cgiar.org/fr/node/47008#.VgEIEX1dckk

(3) CIDSE, Climate-smart Agriculture … or a new era of green washing? May 2015

(4) in April of this year, 60% of the GACSA members coming from the private sector were related to the fertilizer industry

(5) http://www.theguardian.com/environment/keep-it-in-the-ground-blog/2015/mar/25/what-numbers-tell-about-how-much-fossil-fuel-reserves-cant-burn

(6) “In the poorest parts of the world, economic development of some form is still required in order for basic material needs to be sufficiently met. (…) at some stage, “Rich and poor economies will need to converge”: Samuel Alexander in “Prosperous Descent: crisis as an opportunity in an age of limits”, and in “Sufficiency Economy: Enough, for Everyone, Forever” 2015

(7) Samuel Alexander in “Prosperous Descent: crisis as an opportunity in an age of limits”, 2015

(8) Garnett T., Where are the best opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the food system (including the food chain)?, 2010

(9) in opposition to the damaging over simplification of agriculture due to its industrialisation

(10) To date, agroecological projects have shown an average crop yield increase of 80 per cent in 57 developing countries, with an average increase of 116 per cent for all African projects (…). Recent projects conducted in 20 African countries demonstrated a doubling of crop yields over a period of 3-10 years. UN HRC, Report Submitted by the Special Rapporteur on Right to Food, Olivier De Schutter, 2010

(11) Community Supported Agriculture: “Local solidarity-based partnerships between farmers and the people they feed are, in essence, a member-farmer cooperative, whoever initiates it and whatever legal form it takes. There is no fixed way of organising these partnerships, it is a framework to inspire communities to work together with their local farmers, provide mutual benefits and reconnect people to the land where their food is grown” (Urgenci – the International Network for Community Supported Agriculture)

Nous récusons également l’agriculture intelligence proposée par l’agro-industrie et les lobbying de l’alimentation.

Cordialement.

Jean-Louis Marolleau

Secrétaire exécutif du réseau Foi & Justice Afrique Europe antenne de France

Hi there! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading this post reminds me

of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this.

I will forward this page to him. Pretty sure he will have

a good read. Thank you for sharing!

I read this post completely concerning the resemblance

of most up-to-date and previous technologies, it’s awesome article.