This article originally appeared on Fast Company on 12th March 2015

Poverty isn’t just a fact of nature. We made it happen, and we can fix it.

Written By Jason Hickel, Joe Brewer, and Martin Kirk

This is a big year for anyone interested in, or caught in the teeth of, poverty and extreme inequity. It’s the year of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to be agreed by heads of state in New York in September. Right now, tens of thousands of people—from NGOs, to governments, to corporations—are busy negotiating them. They are trying to get your attention, too. Their story is basically this: we’ve halved global poverty in the last 15 years and can eradicate it by 2030, if you support us and accept our story.

There is a hole in the story, though; a mission-critical omission in the logic underpinning it that, unless acknowledged and corrected, will keep all efforts in a tepid “business as usual” box that cannot possibly deliver on its grand promises.

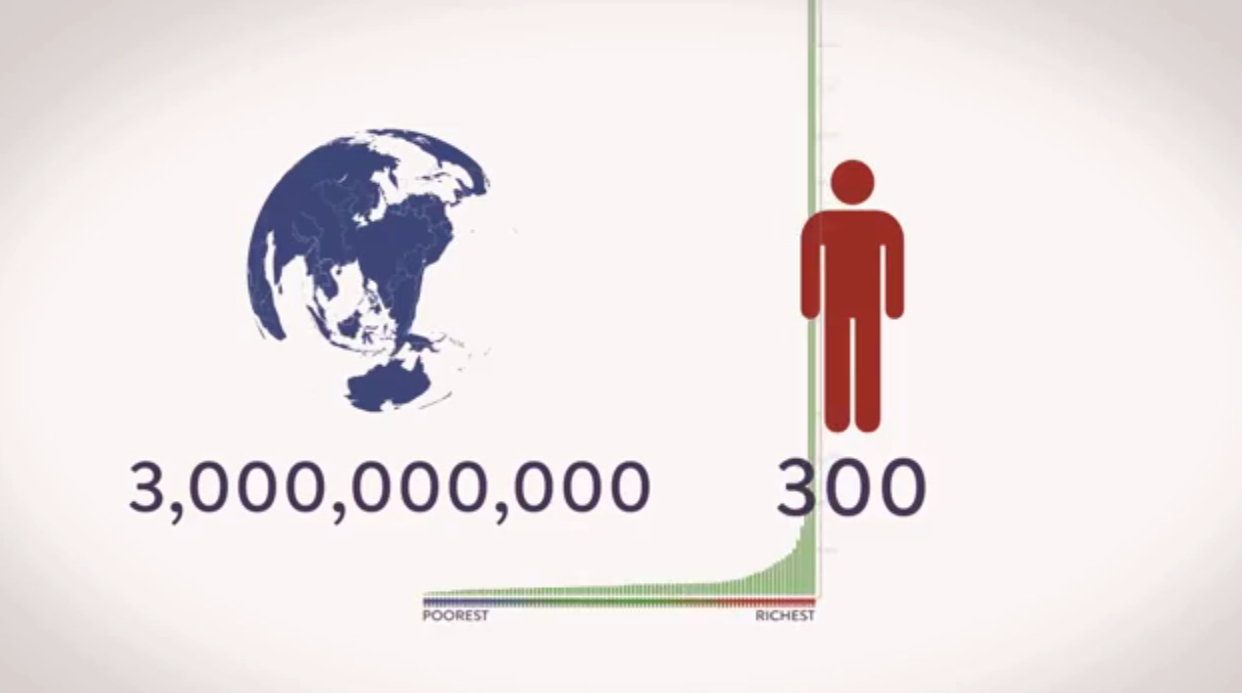

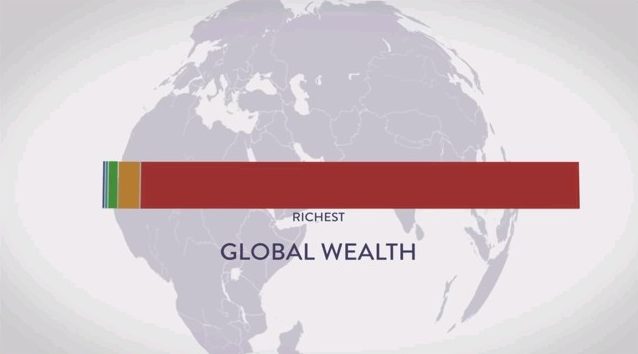

The missing acknowledgement is this: mass poverty, at the level we see globally today (i.e. about 4.3 billion people live on less that $5 a day; the minimum amount necessary, according to UN body UNCTAD, for health and well-being) is created by people. In other words, it isn’t simply a natural occurrence, a common enemy that exists, as if by magic, outside and separate from all the good stuff. Just as humans have created enormous amounts of wealth, so we have created its corollary, widespread poverty. One cannot be separated from the other. Until this truth is embraced, we will be locked into a partial and deeply limited response.

We noted this in the article we published here a few weeks ago: 4 Things You Probably Know About Poverty that Bill and Melinda Gates Don’t, and it rubbed many people the wrong way. It’s understandable that this feels counter-intuitive at first because it seems to defy basic logic. Wealth is something, and poverty is nothing. Wealth is the outcome of action, so it must follow that poverty is what exists before or in the absence of action. In other words, poverty must be a default state. Right?

The problem with this intuitive theory of poverty is that it ignores context— from the quality of education, to race and gender privilege, to physical and mental health, to luck and coincidence and much more. Even more important than all that, though, is the fact that it pretends that what happened yesterday has no bearing on today. When it comes to the global economic system and issues of mass poverty, the all-important yesterday is measured in decades and centuries. If we don’t understand this long view, we don’t really understand anything.

Why is all this so important? Because it is impossible to solve an entrenched problem like mass poverty without understanding how it came into being. There’s every reason to believe we can overcome poverty, if we take the time to understand and learn the lessons from how it is created.

Here are just three ways mass poverty has been created.

1: Closing off the Commons

Before the Industrial Revolution took off in England, most of Europe’s population lived as peasant farmers. We tend to imagine that this must have been a pretty miserable existence; after all, it’s hard to get any poorer than a peasant, right?

Well, it’s true that European peasants didn’t have the consumer lifestyles that we take for granted today. But they did have the most important thing they needed to determine their own futures: secure access to land for growing their food. They also had access to “common” land, which was managed collectively for overlapping uses: grazing for livestock, timber for homes, and firewood for heating and cooking. Peasants may not have been rich, but they enjoyed basic rights of “habitation” that were protected by longstanding tradition.

But this security system came under attack in the 17th and 18th centuries. Wealthy merchants and aristocrats began a systematic campaign to privatize the commons and kick the peasants off their land, which they turned into sheep runs for the highly profitable wool industry. This became known as the “enclosure” movement, and historians regard it as the birth of capitalism as we know it today.

Millions of people were forcibly displaced, creating a monumental humanitarian crisis. For the first time in English history, the word “poverty” came into common use to describe the masses of people who literally had no way of surviving. They poured into cities like London and scratched out a living in sprawling slums—fodder for Dickens’ bleakest novels.

The enclosure movement gathered even more steam once it became clear that it offered a secondary benefit: the impoverished refugees provided the cheap labor necessary to fuel the Industrial Revolution, since they had no choice but to accept the slave-like conditions and rock-bottom wages of factory work. Even small children were sent to the factories by families desperate to survive. And the more people who were displaced from the land, the lower the wages went.

The economic historian Karl Polanyi called this period the “great transformation”.

2: Outsourcing the problem

Okay, maybe early capitalism did produce poverty in England as an initial condition, but surely after this rocky beginning it began to make everyone richer, right?

There is no doubt that ordinary people in England—and in the rest of Europe—have become richer over the past hundred years, and quality of life has improved dramatically. But the humanitarian crisis didn’t just disappear into thin air—it was exported abroad.

Dispossessed by enclosures and suffering miserable conditions in the factories, England’s working class began to riot, and by the 19th century the country was on the brink of outright class war. England’s industrialists realized that, unless they wanted to sacrifice some of their own new-found power, the only way to solve these social tensions was to find new sources of wealth abroad, and new lands and opportunities for the country’s now “surplus” population.

This is what came to be known as colonialism. Land and resources were grabbed across America, India, and Africa at an astonishing pace, and the wealth was funneled back to Europe, where, beginning in the 1940s, it was used to build hospitals and schools and generally improve the lives of the “lower” class. This strategy succeeded in solving many of the social problems at home, but the colonized populations didn’t fare so well.

Land grabs in North America caused the mass dispossession of the continent’s indigenous inhabitants: tens of millions died of starvation and disease. In Africa, European capitalists found that the only way to get Africans to work on their plantations and mines was to appropriate their land and impose taxes. People who had been working their own farms for thousands of years found themselves compelled for the first time to sell themselves for wages simply in order to survive—just like the pattern in England earlier on.

And then there was India. During the 19th century, British colonizers taxed Indian peasants in order to force them to grow crops for export to England. They also privatized the common forests and water systems that Indians relied on to support themselves during periods of low rainfall. So when a series of droughts hit in 1876, more than 30 million Indians died of famine. But there was plenty of food: Indian grain exports to Britain increased by 300% during this period. Historian Mike Davis argues that the British market system was directly responsible for this “holocaust,”

3: The “free trade” paradox

We all agree that colonialism was a terrible system, but thankfully it was mostly over by the 1950s. Since then we have all been focused on development and poverty reduction in poor countries. Right?

Well, after the ravages of colonialism were over there was a time when things started getting better for poor countries. During the 1960s and 1970s, poor countries made careful use of trade tariffs and subsidies to build their economies with great effect. Incomes grew quickly and the gap between rich countries and poor countries began to narrow. In fact, some poor countries became almost as wealthy as their Western counterparts.

But these two decades of hope were brought to a crashing end in the 1980s. The World Bank and the IMF began to impose “structural adjustment programs” on developing countries as a basic condition for receiving international finance. These programs forced poor countries to abandon their tariffs and subsidies, and required them to sell off most of their public services and assets to foreign companies.

According to the “free market” theory popular at the time, this was supposed to improve economic growth. But it turned out that exactly the opposite happened. Per capita income growth was slashed from 3.2% per year to 0.7%. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the average GNP shrank by around 10%, and the number of people living in absolute poverty doubled. It’s difficult to overstate the degree of human suffering that these numbers represent.

Similarly, in 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement forced Mexico to cut barriers to imports from the US. As cheap American corn flooded into Mexico, some 2 million farmers were forced to leave their land. Many had no choice but to seek work in the sweatshops that sprang up along the border.

By 2004, there were 19 million more Mexicans living in poverty than before NAFTA. Today, more than half the population lives below the poverty line, and 25% do not have access to basic food. NAFTA turned out to be like the modern-day equivalent of the enclosure movement in England.

And just in case we think we might, finally, have changed our ways, right now we are seeing a whole new set of trade agreements being put in place that have taken NAFTA as their inspiration, and then super-charged it. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are in negotiation right now, and if passed without major changes they will extend the model across the globe.

When we consider these patterns of poverty creation throughout history, it becomes clear why the story told by many rich governments, philanthropic organizations and nonprofits, both in how they talk about the problem everyday and via grand maneuvers like the SDGs, is so critically limited. Their focus on charity and foreign aid betrays a deeply partial understanding, and offers such simplistic logic that we must wonder whose interests they really have at heart. If we are to have any hope of solving the problem of mass poverty, then we need to rethink the structures and systems that cause it in the first place.

More powerfully, this process of poverty creation—the forceful extraction of commonly-managed assets to serve financial elites—is exactly what recent social movements have called attention to. Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, the African uprisings, even the anti-austerity stance of new political parties in Spain and Greece all have one thing in common: The recognition that the only way for a tiny group of people to become obscenely rich is for huge masses of others to be kept chronically poor.

This cold logic of poverty creation tells us what needs to be done. Before obsessing about amounts of foreign aid, or pretending it can solve deep systemic problems, we need to all focus on changing the rules of economic systems to make them more inclusive, more participatory, more focused on creating well-being than simply extracting more aggregate wealth, and more accountable to those billions who are not being served by the current rules. This is how mass poverty truly can be brought to an end.

Reach the authors on Twitter at: @jasonhickel, @cognitivepolicy, and @martinkirk_ny.

[Top photo: Trevor Kittelty via Shutterstock]

They’ve “halved global poverty” according to whom? Are they basing that on a “third world” data set including China?

Good question Robert. The article isn’t asserting that global poverty is halved, but rather that “NGOs, to governments, to corporations” are claiming this. And it is implied then that this claim is most likely suspect.

So its the “zero sum game” thinking once again? We must accept that poverty and wealth are necessary corollaries, without any proof to back up that assertion? Why is Hong Kong wealthy while Bangladesh is not, given both have high population densities? Point 1) Closing the Commons: Haven’t you heard of the Tragedy of the Commons? What no one owns, no one cares for. Even today in Kenya, the Maasai are being given private land with the result that they are building modern housing rather than mud and dung huts because they can NOW keep the results of their investment. Closing the Commons did displace the less able agrarians, a temporary pain. They were forced to find something else to do, and thus found things they were better suited to. Result, both agricultural and other productivity increased. Increased productivity means increased wealth. Specialization of occupation increases efficiency and productivity. These are basic and well known and proven over centuries of repeated experience.

increased productivity does not (always) means increased wealth. overproduction of goods or commodities will lead to the increasing consumption. uncontrollable increase of consumption will always lead to crisis. well, as we all know, unlimited growth is the ideology of cancer cell.

so, instead of growth ( a holy dogma for any developing and developed nation), we should more focus on sustainability. a reasonable productivity and consumption.

All workers become more productive as new ways of doing things are invented, but somehow most of the new income from increased productivity keeps going to the .01% This is because the market for labor is fundamentally unfair. When there are many sellers and few buyers (even if they buy a lot), the few will always have an advantage in negotiations. And as these advantages make bigger profits that are turned onto political advantage their ability to shape laws and and manipulate other markets, like currency, interest rates, housing, and commodities (which the global banks have all had to admit to) gives them the power to extract wealth at every stage of the economy.

In the US the Great Recession was a 40% transfer of wealth from everyone else to the richest, and they got bonuses for it.

None of this is an accident. And it doesn’t take a conspiracy for like minded people to make like minded decisions.

So next time you hear about the “redistribution of income” ask yourself how all of that productivity was distributed in the first place, and how some poor persons labor became someone else’s wealth.

Yes it is a ‘zero-sum game’. I don’t need to prove to you that it is in a manner that you are asking. To understand what is being said here, one truly needs to be descendant of a slave, or an Askari to the colonial masters.

This is not a scientific calculation where you can add up figures and say here you go there’s a proof. The social world isn’t one something you can divide up in to its parts and access them in isolation. But here we are with you “problem-solving” obsessed techno theoriests who know nothing but scientific hypothesis and try to prove a+b=y.

Try taking a whole view of the globe in its entirety and may be and only may be then might you take a glimpse of your “proof”. But no you are to scientific for us imbeciles.

You know what makes an idiot. Doing the same stuff the same again and again and expecting a different result. The whole Poverty industry, including the do-gooders NGO and the UN are filled with stupid people charged with stupid ideology.

The present didn’t emerge spontaneously with natural imperatives so please save us your naturalising tendencies.

The Tragedy of the Commons was never a tested theory. Someone just thought it sounded right and wrote it down in a book or paper. The truth is, people have over time and in many many places managed various kinds of ‘commons’ such as grazing, water for irrigation, and forests for sometimes hundreds of years, each group designing a system of sharing that worked for that group. It is simply silly to think that humans do not have that ability to forces the end result of cheating on a large scale. Owning ‘resources’ is a very recent phenomena in human kinds existence. Increasing population densities or changing climate definitely make sharing a commons difficult but nothing compares to having you ‘commons’ privatized because nobody ‘owned it.’ The the resource is used to make money for the owners with no concern for the humans who had managed to share a good living from said resource.

For example, the potable water in any given area can be streams, rivers, runoff, ground water, storage ponds and deep aquifers. Most cities through time, came up with a source or sources for water and created city systems that in essence were shared in common and paid for by all. Not to big a problem until the population grows or the water is used by those upstream. The biggest problem is when people want to use the common water supply to make extra money by, say, bottling it and selling it in other towns or drawing large amounts from ancient aquifers to grow cheaper vegies or privatising a city system so someone else makes a profit and makes decisions about the quality of water you receive.

Anyway, ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ like much in ‘Economic Theory’ is just that…. No, not even a theory. It was some guy sitting around and thinking and deciding what ‘probably’ happened to a commons, based on no actual information but what sounded good to him. Get some real factual information! I’m tired of hearing that tired, weak, old idea still spouted as a real fact.

With reference to David’s ‘Tragedy of the Commons: What no one owns, no one cares for.’ Surely the destruction of much of the world’s forests, and certainly tropical rain forests, is the result of large national and international conglomerates owned by their shareholders taking over gigantic areas of the worlds natural resources in their quest to make huge profits at a very high cost to the lives of the indigenous peoples who depend on such forests to sustain them. as they have done for thousands of years.

Interestingly such peoples had, and have, no concept of the private ownership of land. Nevertheless are aware of the importance of preserving and maintaining the environment that nurtures them, and indeed nurtures the well-being of billions of peoples throughout the world.

From the rain forests to the African savannas to the Australian outback and the North American plains, indeed tribal and indigenous peoples everywhere, saw land and the natural world as something to be shared.

Hello, Martin. I read the comments at fastco since you mentioned the article on Gates rubbed some people the wrong way, but I don’t care to open an account there so i’ll say it here:

You do NOT get a personal overfortune of 76 billion dollars by virtue of your own work – that is physically impossible for beings who live in human bodies.

You get to possess 76 billion dollars beCAUSE the human species still has no clue the can of worms we opened when we embarked upon the community project known as division of labor (economists have been using division of labor as an attempted excuse to let pay range billions to 1 while individual sacrifice to working ranges no more than 2 to 1) – – and because myriad ‘unseen’ legal thefts exist in our economic dystems (dysfunctional systems) that serve to (since no sane counter measures have been put in place) ceaselessly and automatically shift wealth from its rightful earner-owners (the 99% underpaid working families) to the overpaid 1% (leisure class).

Bill Gates is NOT working 76 billion times harder than the janitor who sterilizes the surgery room, or your own Mother.

Bill Gates is NOT a GIVER of philanthropy, he is the RECIPIENT of philanthropy, he is, UNJUSTLY, beneficiary of unthinking society’s mad, genosadistic, and ultimately pan-species fatal over-generosity to wealthpower giants.

The rich get richer while the poor get poorer means precisely THIS: the rich are getting more and more for a unit of work while the poor are getting less and less for the same unit of work.

If there is anybody out there who still does not understand that only work creates wealth, now is a great time to prove it to yourself: take a dollar bill out of your wallet and command it to fix you a sandwich.

WORK = sacrifice of a human being’s irreplaceable TIME (and renewable energies). (Note we are not talking here of the work done for all for free by Mother Nature – the first work – because nature doesn’t need a paycheck for the wealth she provided/provides.)

Work is the first condition of staying alive for all creatures who have stomachs that require feeding. Bear catchee fish, bear eatee fish. Bird no catchee worm, bird no eatee worm. For humans it’s the same; the insertion of ‘money’ between ‘work’ and ‘eat’ does nothing to change the fundamental situation we are in.

Money is symbolic wealth, symbol of the substantial wealth, the workproducts of human work. What is supposed to happen in any trade is an even swap of work for work – no one is supposed to be robbed just because we now specialize in our work and thus must trade the products/services we create in order to get the goods and services we need and want. Money is a ticket good for withdrawing substantial wealth from the pool of pooled workproducts produced by human work. The situation our ignorance has produced is this: Bill Gates works all day and a janitor works all day but Gates winds up with 76 billion tickets while the janitor winds up with extreme underpay… and debt… while Gates gets interest on his money, Gates gets a ton of money for no work done – the money is just sucking more money in interest payments – and again, the money is coming from others who worked for underpay, NOT from God!

Humans are either going to get real and re-spread world wealth as equally as the work in the world is spread or we’re going extinct. Injustice drives violence – humans reliably retaliate when you hit them – stealing their work is hitting people very hard – the stealing is giga-extreme and growing – the predicted violence is proportional to the injustice – it is growing – every theft comes with an angry person attached – everything changed when uncle al discovered that E = mc2 – the hairtrigger bombs are global – the future is approaching at the rate of one second per second – the worst is not going to just slink away too ashamed of itself to happen.

The enemy of humanity is an IDEA – a bad idea – the worst idea that ever entered a human head is stuck fast in every human head – it’s a terrible idea to allow people to take more from the pool of wealth than they contributed by virtue of their own sacrifice made to working – it’s a RATIO that is roiling, boiling, and spoiling this world – the ratio of overpay to underpay – pay in this world ranges from a thousand dollars per second to a thousand dollars per lifetime – – again, while the sacrifice to working, to producing the goods and providing the services ranges no more than 2 to 1.

The pool of wealth is finite. That means overpay has nowhere to come from but from underpay. When somebody is allowed to take more from the pool of wealth than they put in by their own work it forces others to take out less than they put in by their work! God does NOT drop Bill Gates’ pay from the sky. The money he has came across the counter out of people’s wallets – it came from people who don’t understand money, work, and wealth so they don’t realize they’re donating philanthropy to a freebie-getter.

It is way past time to remarry the amount of reward got to the amount of sacrifice to working given. This is the root, the key. Found at last. Don’t do this, don’t fix pay unjustness, and you fix nothing – your problems are growing faster than you can pull leaves. Money is power. Everybody knows. We haven’t time nor right to go on seeking consensus agreement on answers to all the wrong questions – we are only making more work for ourselves and leading ourselves into hope fatigue by attacking a few of the millions of extremely negative consequences of allowing overpayunderpay – we are straining gnats whilst swallowing the camel of overpayoverpower-underpayunderpower.

Fairpay Justice is the only answer, has always been the only answer. We can have fairpay justice and a happy, safe, healthy and prosperous planet or we can have overpay-overpower/underpay-underpower history on repeat on steroids kaboom.

Wake up and smell the uranium, Humanity.

Make the investment in justice and reap the greatest-ever dividends.

Or … is the market for justice, equality, survival and happiness all dried up?

Hungry, first I would like to address the “unjust” billions of Gate’s foundation. Before Microsoft a software industry did not exist. Invention and implementation of Windows platform not only made it possible for other Microsoft employees to get wealth but, but also created a lucrative career options for the people who wanted to develop for the system. Career options such as programmer, software architect, game developer and so on. Trust me Bill Gate’s is not the reason why someone else is poor he is wealthy because he created an ecosystem. An ecosystem that is not has many other companies and generates around 350 billion revenue every year, that is not including all the salaried employees that are now have jobs.

Now coming back to the article, I do agree with the thesis that free trade policy is in many cases is unfair and should not be implemented in developing world. Agricultural revolution, industrial revolution and colonization has been thoroughly studied by historians, and I would agree that agricultural and industrial revolutions are fundamentally connected, colonization is a separate story. To argue that those revolution made people poor is simply historically inaccurate. Colonization on the other hand was transferring the wealth, and now generally agreed that it was a bad and unjust thing to do.

I’m not sure if it was intentional, but it seems you are arguing your point based on the labor theory of value. You might want to rethink on a basis of the subjective theory of value. This basis makes it somewhat easier to justify differences in income from labor.

I do think you are correct, though, in that labor, however valuable, it is not sufficient for justifying the wealth concentration in question. There are other factors at play here, not least the appropriation of the commons by patent and copyright laws, or the anti social behavior of treating source code, a resource that cost nothing to reproduce, as an exclusive asset, and other similar institutions that together helps in creating, and sustaining, an owning class, with the power to extract rent.

Don’t forget the role of imposing scarce national currencies and then forcing people to pay taxes in it, wiping out the local subsistence economy:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hut_tax

“Hungry” – I agree about all of the statements you make about work being a part of weath creation.

Another area of theft was created when natural resources could be owned by those who were given title, or sold title for far less than the ultimate worth of the resources. While it took work to extract those natural resources, a high value was also put on the resources themselves, now owned by private interests. This conveniently broke the tie between how much time someone had to work to get wealthy – some could sit back and allow others to extract, process and sell the resource based goods, while collecting the benefits of resource ownership – control of the capital.

That’s a succinct explanation of poverty in poor countries. There, is of course, plenty of poverty in the relatively wealthy countries – what would be the succinct explanation for that? What I think is also worth noting is that there is a correlation between the inequality within countries and violence. For example two countries that have great internal inequality also have a great level of violence – USA and South Africa (it has been said that the latter has more inequality now than during the Apartheid era).

This is the most down-to-earth and well articulated explanation of the “how” we got to this dismal state of our human civilization that I have ever read. Kudos to the writers!!

It clearly and arguably reveals the truth that “ownership” of the land (as in capital ownership), is not compatible with a sustainable global civilization. One must consider the trend that we are currently engaged, ie: fewer and fewer individuals of the global population who claim to be “owning and controlling” more and more of the global wealth in its’ resources. Thus, dispossessing the greater and growing “masses” of humanity.

This trend if followed/pursued long enough would result on one day where only one individual would “own” and “control” the entire world.

It seems reasonable that, that “one person ownership” will never occur. Methinks that either we will come to an “intelligent adaptation” to our quest for sustainable civilization, or; we will crash the system and the biosphere and cause the extinction of our own species. I suppose that we could wake up due to the consequences of our erroneous exploits upon the planet and revive sensibility within the human species,…. perhaps?

None-the-less, it seems evident to me that the restoration of the “Commons” ethic is compatible with global community development where the locus of control over the resources is put to the local communities to where “sustainability” means something for generations of humanity social well-being and long term exisitence. Today’s world is about immediate control measured by bottom-line reports and election/power transfer politics.

What ever the outcome of those of us who reside within this fragile bio-sphere, the earth will go on as long as the sun’s forces hold it in place and orbit….. but, still some day, this earth will be a lifeless spec dust in the grand universe. Perhaps?

Today, yes, we should busy ourselves with an honest set of endeavors that assure a course for an ever-advancing civilization for our posterity. That will probably embrace the elimination of the extremes of wealth and poverty from our human civilization.

1. Polanyi was right, privatizing the commonwealth (of lands) created poverty and drove surplus, starving, and displaced peasants into the Dark Satanic mills — which in many other countries later was partially solved with ‘Land Reform’ (or more broadly with ‘Asset Reform’).

2. Colonialism kept the gin-addicted poor of London from revolting by using “half the world’s resources to support the homeland”, and keeping the masses in England ignorant of the deaths caused at the tip of the spear ‘abroad’.

3. Yes, the violent ‘tip of the spear’ was replaced by the ‘tip pf the financial pen’ allowing the evolving system of wealth extraction and accumulation of more horded capital to be gathered with less visible violence via debt peonage.

So what’s the ‘plain language’ name of this awful, but unrecognized, system that builds wealth and poverty by evolving and disguising itself over centuries?

Awesome read ! What people don’t understand is that poverty is not an individual problem but a social problem. Hopefully we get a grip before its too late …

Very easy, simple and brilliantly written….kudos to the writer to put it simply without any rhetoric and data mountains. And the striking story is at the individual level every billionaire industrialist barring a very few are just trying to increase the zeroes between themselves and the lot they once come from. As on the face of it, it’s the job of the elected government’s to take care of the poor lot, who in reality clandestinely bid the same masters and rob the natural resources and deliver it to the rich. As there are no more nations to colonise and slaves to trade…..save the planet please