The annual public letter from Bill and Melinda Gates has become a much-celebrated event in the global development calendar. But lost in the excitement around this year’s letter is the fact that it uses 6,000 words to paint a picture that is so selective in its use of facts that it amounts to little more than propaganda for a failing industry, and indeed a failing ideology.

And the 2017 letter is especially striking for just how out-of-sync it feels with the zeitgeist.

The Gates’ used their letter to respond to Warren Buffett, who in 2006 gave a staggering $44 billion to the Gates Foundation – the largest charitable gift of all time. Ten years later, he asked them to reflect on what they had done with it.

The couple selected a handful of positive global trends and claimed them all for the foundation. They do not distinguish the achievements of rich philanthropists and donor agencies from the achievements of all the governments, U.N. bodies, multilateral institutions, businesses and social movements that are devoted to global development.

More importantly, they fail to offer a single critical reflection on the work they have done.

This isn’t transparent, accountable philanthropy. This is the world’s most powerful foundation cherry-picking data to fit a good-news narrative to generate a sense of optimism they feel is sorely lacking. Indeed, the letter more or less boils down to a single claim: “The world has been getting better over the past 25 years, and as long as we keep doing more of the same, it will continue to get better. Trust us.”

There are two big problems with the letter. First, some of their examples are just wrong. Second are errors of omission. There’s a lot they just don’t talk about.

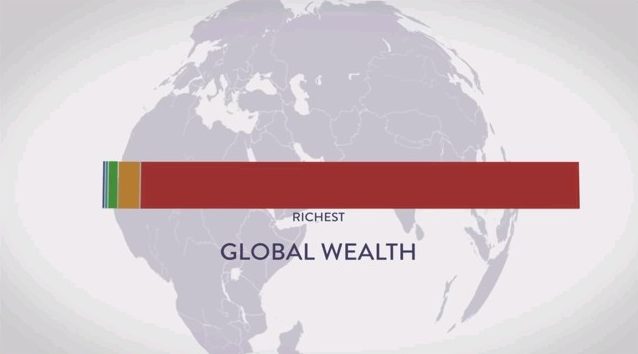

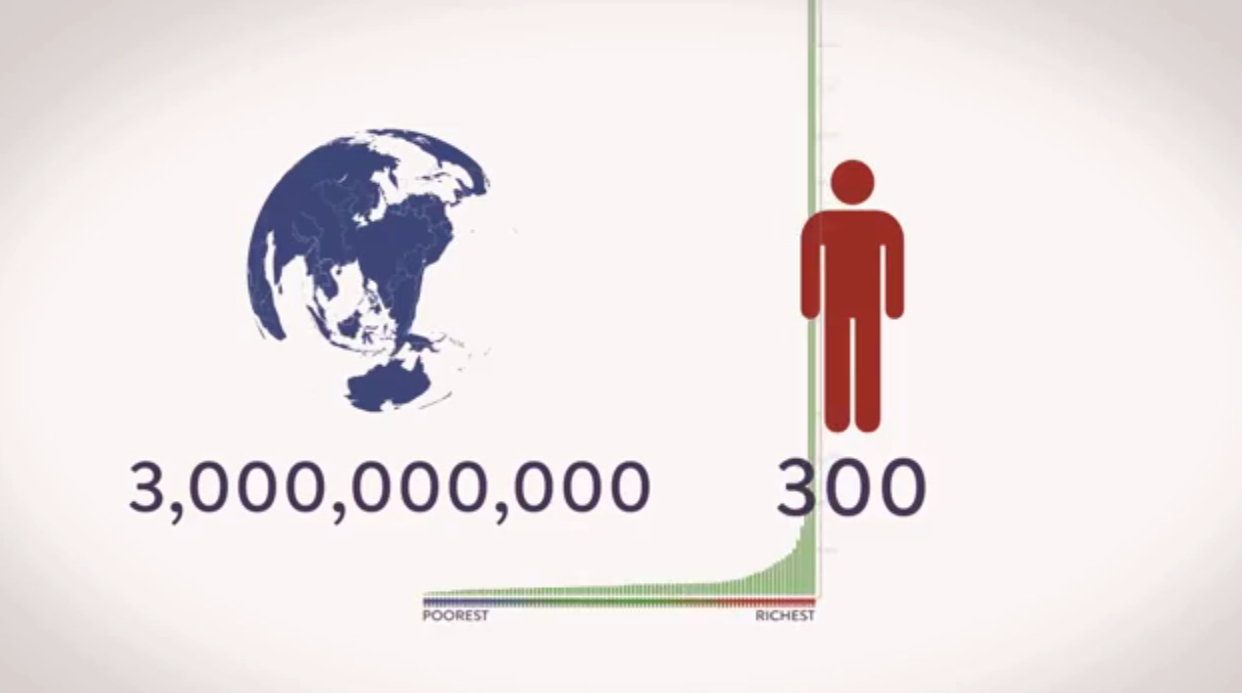

A prime example of the former is their headline claim that poverty has been cut by half since 1990. They use figures based on a $1.25 a day poverty line, but there is a strong scholarly consensus that this line is far too low. A more accurate poverty line is $5 per day, which, even the U.N. Agency for Trade and Development suggests this is the bare minimum necessary for people to get adequate food to eat and to stand a chance of reaching normal life expectancy.

Global poverty measured at this level hasn’t been falling. In fact, it has been increasing – dramatically – over the past 25 years. Today, more than 4 billion people live below this minimum threshold. That’s nearly two-thirds of the world’s population. The Gates’ would be wise to reflect on this fact, for it is a clear sign that the development industry is failing at its main objective.

Why is development failing? This brings us to what the Gates’ letter omits. The letter focuses so unwaveringly on foreign aid that you’d be forgiven for believing that charity is all that’s needed to address poverty. We hear nothing of the systemic forces that drive poverty and inequality in the first place, such as – to name just two relevant examples – tax evasion and avoidance, and intellectual property rights.

Poorer countries lose in excess of $1 trillion per year to illicit financial flows. An estimated 83 % of this is siphoned away through a practice called trade mis-invoicing, whereby companies deliberately misrepresent the prices of traded goods in order to spirit money into offshore secrecy jurisdictions, usually to avoid paying taxes. These illicit flows outstrip annual aid contributions by a factor of seven

Even when money may be being moved legally, the extensive use of tax havens by most multinational corporations adds another layer of extraction through technically legal but morally offensive tax avoidance. Microsoft, for example, currently has around $108 billion in offshore accounts. This is the sort of money that the former chair of the U.K. Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner, calls “socially useless”: It has been removed from general circulation to protect it from taxation, which means it doesn’t contribute its fair share to the general pot for education, health-care, infrastructure, or even the foreign aid the Gates’ say they want more of.

Then, there is the omission of intellectual property rights. This is extraordinary given the vital role they play in enabling poor countries to climb out of poverty. Intellectual property rules are set and managed through a trade agreement called TRIPS: Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.

Large U.S. companies, such as Microsoft – under Bill Gates’ chairmanship – lobbied hard for this agreement as they make 60% of their profits from licensing and patents. When TRIPS came into force, it forced developing countries to spend an extra $60 billion per year in additional patent licensing fees, to access technologies and medicines that are essential for development. $60 billion is half of all foreign aid and about 15 times more than the Gates Foundation distributes.

Most striking of all, climate change doesn’t get a mention in the 2017 letter. We know that climate change is caused almost entirely by historical emissions from rich countries, but its impact is overwhelmingly felt in poor countries. It is already costing developing countries around $570 billion a year in damages and lost revenues. And it is set to get much worse in the coming years. The U.N. calls it, “a major and growing threat to global food security” that could push 122 million more people into extreme poverty by 2030, Most politicians have now admitted is one of the most serious threats we face. It is remarkable that it gets such short shrift by the Gates’.

Changing that system at its root – by stopping illicit financial flows, shutting down tax havens, creating a fairer trade system, battling climate change and helping to build resilient local economies and communities – would require those with power and wealth to dismantle the very machine that created their privilege. That sounds unattainable but if the Greek roots of the word philanthropy literally mean for “the love of humanity” surely such drastic change that would benefit people and planet is the point?

This critique of the Gates’ letter shouldn’t detract from the fact that there has been considerable progress in human development in recent years. Illiteracy, child mortality, access to family planning services have been heading in the right direction. The Gates Foundation has undoubtedly made some valuable contributions to this work, particularly in the area of vaccines, and that should be acknowledged and celebrated.

But to tell such a reductive, self-aggrandizing story isn’t optimism, it’s deception. It is false to think that we can get lasting change by only speaking of what alleviates some of the worst suffering while ignoring almost everything that causes it. It is also disingenuous to claim that poverty can be eradicated with more charity and foreign aid. Yes, the world needs good news but not at the expense of real change.

As I understand the Gates Foundation, its funding ‘principal’ (not principle) is still vested in the corporate profit machine (including petroleum extraction), which by many assessments causes more damage to the beneficiary countries than the 5% dividends can mitigate. On the other hand, they have recently raised the issue of over-population as a contributing factor to worldwide environmental degradation. So, while their approach may in-and-of-itself have little positive effect, it at least raises a possible avenue of dialog–other than neo-liberal control mechanisms of black-mail, bribery and military might…

Thanks for the comment, Jim. Yes, they certainly do still have a lot of their money invested in the corporate profit machine. They are, in effect, an externality of the neoliberal system; helping to mop up some of its worst excesses and put a good face on it. In doing so they are, of course, protecting the machine. There’s an old Oscar Wilde quote that I think captures the problem quite neatly. It’s from a specific time and place, but the truth it points to is as relevant for the present moment as it was for Victorian England.

“Just as the worst slave-owners were those who were kind to their slaves, and so prevented the horror of the system being realised by those who suffered from it, and understood by those who contemplated it, so, in the present state of things in England, the people who do most harm are the people who try to do most good”

The whole short article is pretty great https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/wilde-oscar/soul-man/

Just a picky proofreader comment: In the fifth-to-last paragraph, the word “million” is missing after “122” and before “more people.” Clicking the link makes it clear, but you might want to fix that soonliest.

Thanks Jake. Good catch.

I read somewhere that the elite use philanthropy as a PR move while the money gets invested in industries the philanthropist has a stake in. It appears the Gates’ use that model effectively.

Philanthropy impact measurement usually stops at the gift or donation level… E.G. We gave $5 million to AIDS research, rather than looking at the genuine impact it has on the people and the environments they are claiming to empower. We need better impact measurement rules that demand total transparency with philanthropic giving. After all, we’ve been donating and giving to developing counties for years and poverty isn’t going away! So many times our philanthropic giving actually makes the problem worse, leading to government & corporate corruption and forming a dependence mentality in the recipients. A great impact measurement case-study is Krochet Kids // A Social Enterprise in Costa Mesa, CA. Check out their impact measurement here: https://www.krochetkids.org/what-we-do/our-impact/

Philanthrophy =hypocrisy.

“Rockefeller said of the University of Chicago. “It is the best investment I ever made.” innocently one could believe that he meant the investment in educating the youth, but by reading;

PROBING THE ROCKEFELLER FORTUNE

A report prepared for Members of the United States Congress November 1974, which the diligent reader may wish to do at this time. One sees that philanthropy, Rockefeller style, meant the Rockefeller Foundation maintains control of their education bequeaths/ investments, and in controlling how the money would be invested, ensured that it was reinvested in their own best interest.

”Our goal like everybody else’s, is to make wads and wads of money for the family.” RF&A associate Charles B. Smith. [18]

Philanthropy and charity has morphed into a self-congratulating act of deep hypocrisy. The public relations industry is to blame here too. After the Ludlow massacre, J.D. Rockefeller Jr. felt the family reputation urgently needed some polishing, enter Ivy Lee, spin doctor extraordinaire, who ensured that when old man Rockefeller died, the public saw him as a great humanitarian. [19, 20, 21] Forgetting entirely that this mans’ business methods were, and continue to be, the cause of massive inequality and poverty that create the need for charity and philanthropy in the first place. Had he been more of Henry Fords mind…

“What right have you, save service to the world, to think that other men’s labor should contribute to your gains?”

– Henry Ford.

…the need for charity may not have been necessary, which was after all the whole point of democracy and this socio-economic experiment that we call the US.

No matter how prettily you ice a cardboard cake, when you slice away the sugar coating, it remains cardboard.”

An extract from Searching for Galileo

celebrity philanthropy is showbiz and has nothing to do with the ell being of others.

Hi, Interesting article!

I agree with you that extreme poverty (say at the 1.90$ PPP level) decreasing isn’t everything and we should also look at a more general poverty level (say we use the 5$ PPP line).

However, I’m a bit confused by your claim that the world has gotten worse respective to that poverty line despite extreme poverty falling. I checked your reference which I’m assuming to be the Guardian article you link to.

It says that in 2015 4.2 billion out of roughly 7.3 billion live below this poverty line, which is 57% of the population. (The author claims it’s more than 60% which I’m also confused by, but maybe he was relying on old population level data.)

He then continues: “And the number has risen sharply since 1980, with nearly 1 billion people added to the ranks of the poor over the past 35 years.”

So the amount of people on this level of poverty or below was about ~3.1 billion in 1980 according to him. However, the world had only about 4.5 billion people in 1980, which indicates about 68% percent of the population falling below this poverty line.

Moving from 68% to only 57% is admittedly not an amazing improvement, but not too bad either and I certainly wouldn’t call it getting much worse. Or are you intentionally not adjusting for population growth and consider the absolute number of people in poverty more relevant?