Weekly Research Report for October 15, 2014

Purpose of This Report

Last week we looked at the history of the social movements against elites who use globalization processes to rig political and economic systems in their favor—a sequence of protest events that draw more people together from around the world with each new wave. Common themes include everyday people versus elites and policy mechanisms used to extract and horde wealth. I noted that TheRules.org itself is an outgrowth of this evolving cultural process.

Ironically, the rise of these social movements has been made possible by many of the same globalization processes. The opening of national borders to trade, meteoric adoption curves for communication technologies, and a new IT backbone (the internet) are all consequences of globalization.

How can this be? Are social justice activists REALLY opposed to globalization? It was the corporate-owned media that framed the movement as “anti-globalization”, after all. This label didn’t come into wide use until after mainstream news reports about the 1999 World Trade Organization protest in Seattle. Why were socially progressive activists framed as being against globalization?

More disconcertingly, why did many activist groups adopt this label when it was painted onto them by the very same corporate actors they oppose? The movements that are converging in this space have an identity problem. We never took the time to look at the frames of the debate. And now, we are at odds with ourselves—conceptually in the ways we describe what we are for and against—making it difficult for us to tell a compelling story that brings all of us together around a shared agenda.

This points toward the purpose of this report. A comprehensive evaluation of the entire discourse is beyond our scope. Rather I want to establish a few lines in the sand—map out the largest structures inherent in the semantic frames that help and hinder us.

Who Is Actually Against Globalization?

I have recently been exploring the systemic risks that arise from globalization. The complexities that emerge in our vastly interconnected world make it difficult to comprehend the causes for global events or assign blame when harm occurs. Specifically, I have been reading an excellent book called The Butterfly Defect: How Globalization Creates Systemic Risk and What to Do About It by Ian Goldin and Mike Mariathasan.

I have recently been exploring the systemic risks that arise from globalization. The complexities that emerge in our vastly interconnected world make it difficult to comprehend the causes for global events or assign blame when harm occurs. Specifically, I have been reading an excellent book called The Butterfly Defect: How Globalization Creates Systemic Risk and What to Do About It by Ian Goldin and Mike Mariathasan.

An argument is presented that globalization is only resisted by right-wing groups with xenophobic or protectionist sentiments. These are the people who—often motivated by insecurities about local jobs or racist sentiments—fight against open immigration policies that make it easy for workers to move across national boundaries.

These people try to shape trade agreements (and domestic policies) that serve national interests—a frame that conceals their true intentions—as a pushback against globalization of the workforce.

This begs the question, What is globalization? For a long time, it has been equated with neoliberal economic theories and expansion of corporate power. A correlation does exist. But are they the same thing?

Said another way, if an activist is against a financial elite that games the economy to benefit the super rich, does this also mean they are against open borders and global communication? I would like to suggest that this confusion comes about because the frames at play in the discourse have not been clearly (or intentionally) articulated to make the differences obvious.

What Is Globalization?

I t is important that we answer this question in the generic first. Ideology and worldview can easily distort our definitions. I decided to look at Google Image Search and see what came up.

t is important that we answer this question in the generic first. Ideology and worldview can easily distort our definitions. I decided to look at Google Image Search and see what came up.

This text box was among the first things I found. Note how the definitions describe globalization as the removal of geographic constraints, increase of worldwide interconnection, and growing interdependence.

It is historically true that business activities—and increasingly, multinational corporations—have driven this globalization process. What I find interesting is that other cultural expression arose at the same time, including:

- Ethnic mixing and the breakdown of tribal boundaries, promoting the universalist values of human rights, equality, and shared dignity regardless of race or cultural identity.

- A “cosmopolitan” mindset in major cities that is increasingly global in perspective and inclusive of previously divided social geographies associated with different places.

- The idea of the human race, that we are all part of the same global family and are in this together.

In other words, the cultural dimensions of globalization are where the semantic frames of universalism arose. It would not be possible to articulate a notion of global social movements without globalization! Paradoxical, I know.

Some of the Frames for Globalization

The definitions given above are value neutral, by which I mean that they could be good or bad, depending on how we look at them. Social movements are never value neutral. They always come from a place of critique or moral transgression.

This can be seen in the images below.

The Global Elite

Figure 1 presents one understanding of globalization that members of /The Rules are likely to sympathize with. A cabal of global elites, all white men in suites, sit around a table and make decisions that serve themselves.

This is the quintessential back room deal. It is easy for people to operate using clandestine methods in the absence of transparency and accountability that arise in complex, decentralized, multifaceted global systems. The movements around corporate transparency, legitimate governance, and open access all arise from a perspective like this.

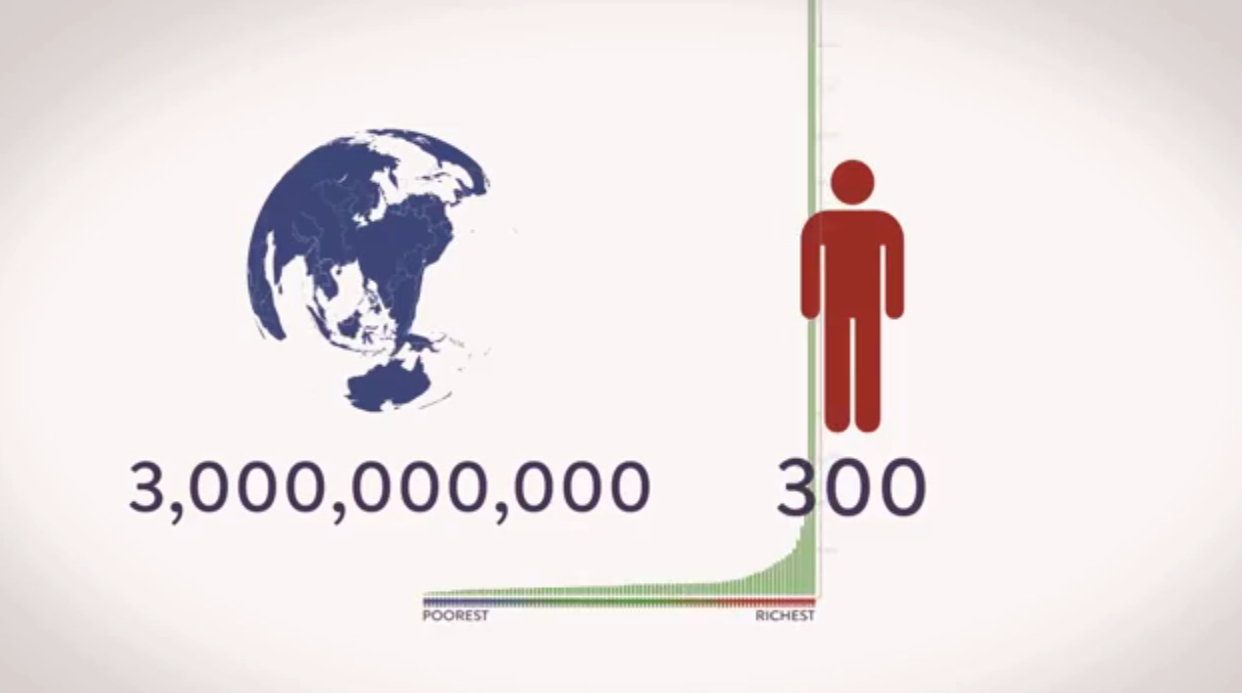

Another common story (that I have helped promulgate, for good or ill) is that many of these elite decision makers are sociopaths. They run the world faster and faster—as depicted in Figure 2—with no concern for all of the people who get left behind.

The elite are winning the race

This story draws attention to the fact that many leaders are insensitive to the harms they cause. Their morality is thought to be damaged in some way. Perhaps they are emotionally broken, or just plain evil. The kernel of truth in this narrative is that globalization HAS INCREASED INEQUALITY both within countries and globally. The unanswered question (that we address in our frame analysis on poverty ) is how this happens. The causes are obscured until the right story makes them clear.

Another depiction of globalization can be seen in Figure 3. Trade agreements have not been set up to “open markets” on a level playing field. They give strategic advantages to whomever writes the agreement.

Globalization as unfair trade

This is how theft and plunder enter the scene. Globalization is a process of increasing interconnectivity on the world stage. If that interconnectivity is used to extract wealth by powerful actors, then globalization is a process for creating poverty and increasing inequality. This points to the rules-of-play and how the game has been rigged.

What is missing from these depictions is what Figure 4 is all about—the fact that our world has become more safe and prosperous (by some important measures, though less so by other measures) because humanity is now connected across the globe.

This view of globalization draws attention to the creative potential of 7 billion educated humans. It is a reminder that everything is connected. What happens in one part of the world will impact other places—the quintessential lesson of global pollution and climate change.

Globalization as a connected world

Our collective knowledge has grown because different cultures interact and share what they learn. Each of us in these social movements has benefited from this cross-pollination of people and places. We are definitely not anti-globalization in this specific sense. Indeed, it is our recognition that all people are worthy of respect that compels us to strive for social justice at home and abroad.

At the same time, we now must confront new challenges. There have been three global pandemics since this century began. The current Ebola outbreak is quickly becoming number four. Studies have shown that previously isolated disease outbreaks can evolve into global pandemics in three days if an infected person visits a major airport hub.

Similar risks arise in other parts of our globally interconnected system as well—cascading shocks from natural disasters, disruptions to fragile global supply chains, anonymity in global finance that lets criminal activity hide within the obscurities of complex networks, and much more.

Addressing these systemic risks of globalization will require cooperation and legitimate governance at the transnational and global scales. So we need to get clear about which parts of globalization we are against.

What Can We Learn From This Brief Analysis?

It is very important that we parse the good from the bad when it comes to globalization. Most activists who stand against corporate power and the rigging of economic and political systems are our common humanity that comes with our global perspective that is uniquely modern.

Preserving this feature of our conceptual landscape while we scrutinize the illegitimate forms of governance and systemic effects of globalization will be key to navigating the “wicked problems” in our midst.

With this in mind, I would like to suggest a few discussion questions:

- Why is it important to look at these different frames? What happens when we start to see the different perspective? How do we gain clarity about effective strategies that lead to meaningful and substantive change?

- What are the features of globalization we support? How do we work with partners around the world to achieve planetary-scale objectives? What can we do to make these features more clear where alliances can be forged to achieve our goals?

- Specifically, what are we against? Just as importantly, what are we for? How do we separate wheat from chaff and get really clear about what needs to change?

I hope this brief report helps us begin to clarify what our movements are really about. For myself, I have come to the conclusion that I support globalization as a process of recognizing our common humanity and serving each other at the planetary scale. I am opposed to opaque and unaccountable behaviors that game the global system for personal gain, while placing others at risk.

Of course, I am curious what comes to mind for you.

Excellent report. I agree with your brief analysis and with your conclusion. As you put it so nicely, “[o]ur collective knowledge has grown because different cultures interact and share what they learn. Each of us in these social movements has benefited from this cross-pollination of people and places. We are definitely not anti-globalization in this specific sense. Indeed, it is our recognition that all people are worthy of respect that compels us to strive for social justice at home and abroad.” “For myself, I have come to the conclusion that I support globalization as a process of recognizing our common humanity and serving each other at the planetary scale. I am opposed to opaque and unaccountable behaviors that game the global system for personal gain, while placing others at risk.” Thanks for sharing your knowledge with the rest of us.