Panama’s efforts to gain funding for standing forests roiled by indigenous opposition

There isn’t a word or phrase in the Kuna language for “carbon trading,” and much less for something as complex as REDD+. Standing for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation, REDD+ is the worldwide UN-backed climate change mitigation scheme that relies on carbon trading within forest landscapes to fund forest conservation programs. And yet, since 2008, the Kuna people have been hearing lots about it and referring to it often in their private conversations.

“It has something to do with the value of our forests to non-Kuna people,” said a young man to me recently, trying to explain REDD+. “I only know that I don’t agree with it.”

A majority of the indigenous Kuna reside on just under 40 of the 365 islands that comprise the San Blas Archipelago in eastern Panama, an area known as Kuna Yala, or ‘land of the Kuna.’ They depend on fishing, subsistence farming — including crops like banana, coconut and sugar cane — and eco-tourism for their livelihoods. On the mainland the Kuna also possess rights to a vast old-growth coastal forest, which they have managed sustainably and communally for hundreds of years.

Ustupu Island’s chief saila, or cultural leader, Leodomiro Paredes (with his wife, Imelda) played an integral role in the Kuna’s deliberations about the UN-backed REDD+ climate change mitigation plan. After five years of discussion, the Kuna roundly rejected the plan in June. Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra.

One of the reasons many people in Kuna Yala haven’t embraced the REDD+ program has to do with the fact that Panama’s negotiations happened behind closed doors. In April 2007, without first consulting with the Kuna, representatives of the Panamanian government met with World Bank officials in Berlin to hammer out the details. The lucrative carbon offset deal basically meant that Panama would be offering up the Kuna’s well-preserved forest as part of a solution to worldwide deforestation rates, even though the indigenous group has total control of their forests according to the Panamanian constitution.

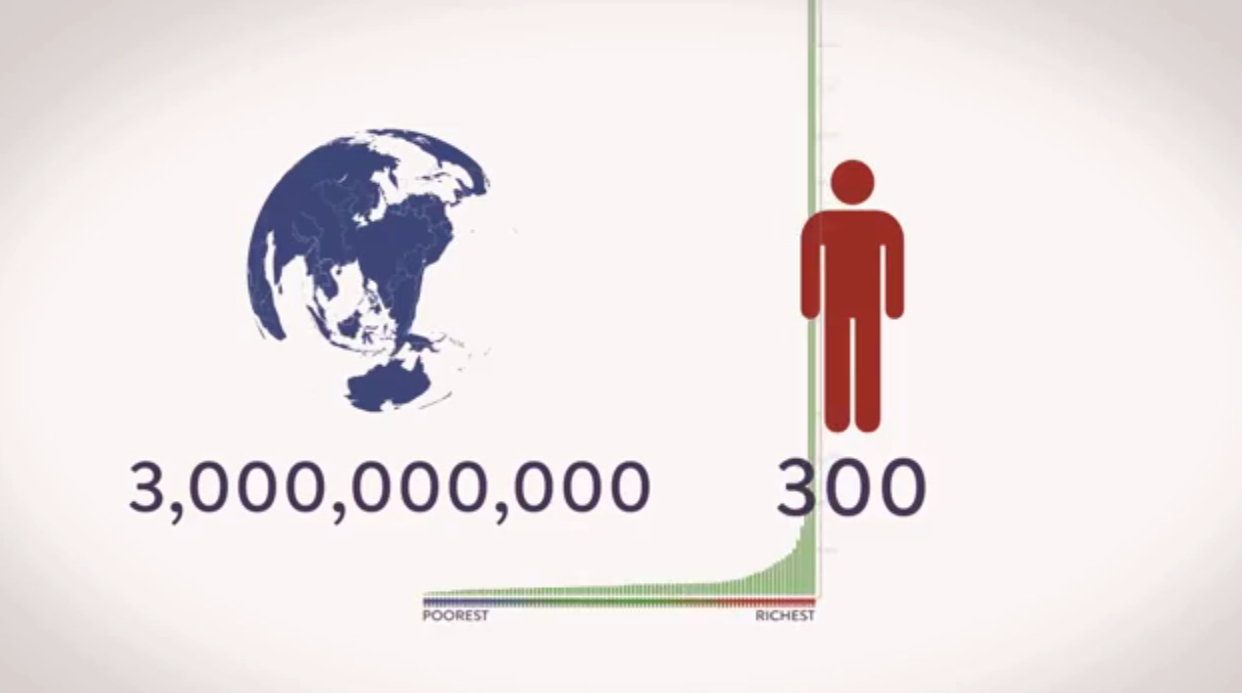

Over 12 million hectares of forests are lost every year worldwide due to deforestation releasing carbon into the atmosphere. Paying forest-dwellers to keep trees standing is REDD+’s important mandate, but one that doesn’t sit well with many indigenous peoples, including the Kuna.

For them, the forest is sacred. Before a tree is to be cut for building materials or to make room for subsistence agriculture, men sing to Nabgwana, or Mother Earth; they sing to the air, and to nature’s spirits in an effort to explain the felling of a fellow species.

The Kuna’s forest occupies more than 3,240 square kilometers (1,250 square miles) along the northeast corner of the country, near the border with Colombia. But unlike what’s left of forests in other indigenous communities throughout Panama, the Kuna’s land is primarily lush, old-growth forest and among the best preserved in Central America. Hundreds of species of hardwood trees such as caoba and cocobolo grow near the rivers, providing the Kuna with the wood they need for their thatched roof huts and cayucos, or dugout canoes. Deeper inland, where the bonigana — or natural spirits — dwell, there are innumerable medicinal species of herbs, roots, and fruits that the Kuna still use on a regular basis to keep strong and healthy. And when the sun sets, tapirs, jaguars, peccaries, and countless other species emerge from the shadows of this dense forest as they look for food. Sometimes, they end up as food themselves.

As the sun rises, clouds and mist begin to clear over some of the tree-covered mountains in the mainland forest in Kuna Yala. Panama’s indigenous Kuna have managed their forests communally and utilized them sustainably for several hundred years, and today possess some of the best preserved old growth forests in all of Central America. Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra.

Although this isn’t necessarily virgin territory in the sense of being a forest untouched by man—and there are arguably very few, if any, of those left on the planet–it is a rich ecosystem that has thrived for hundreds of years under the Kuna’s care. For that reason, it is of great value to them — so great, in fact, that they cannot put a price on it.

This is how REDD+ would work in Panama: a multi-billion dollar conservation package financed by the World Bank, alongside wealthy countries like Norway, the U.S., and the UK, would set aside carbon-absorbing tropical forests in developing countries in order to reduce greenhouse emissions. As long as those forests remain standing, the first $12 million pledge would flow from REDD+ funders to the Panamanian government. But before this could happen, the government needed to secure approval and participation of the indigenous populations living in those earmarked forested areas.

The prospect of having to set any of their forest aside is difficult for the Kuna to grasp, especially given the community’s hard-won sovereignty.

In September 2009, Kuna environmentalist, Onel Masardule (center) met with an elder in the island village of Malatupu to discuss REDD+. During deliberations about the plan, workshops took place throughout Kuna Yala to educate the community about the potential positive and negative aspects of REDD+. The Kuna ultimately voted against the plan in June 2013. Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra.

“The Kuna people feel that many institutions, NGOs, and governments are taking advantage of them,” said Heraclio Herrera, a Kuna biologist who has helped educate the island-dwelling communities about REDD+ and the carbon market. “We’re open to getting help, but we want others to respect the forests because they don’t belong to us; they belong to our creator.”

Benoît Bosquet, coordinator of the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, was tasked with helping nations prepare for the program. After that initial Berlin meeting, Bosquet visited Kuna Yala to hold informational workshops about the benefits of REDD+. But he found himself having to explain everything that the program was not.

“They won’t get their land taken, this is not what an institution like the World Bank has in mind,” he said, addressing Kuna fears about losing land tenure under the climate mitigation program. “No one will be forced to participate.”

Between 2008 and 2013, a series of meetings were held throughout Kuna Yala by a number of different players — international NGOs invested in a “yes” vote, small local nonprofits doubtful of REDD+, and, of course, the World Bank. The agency spent $250,000 to try to woo the Kuna and Panama’s other indigenous communities.

One of Kuna Yala’s densely populated islands seen from the air, and beyond, the Kuna’s sacred forest – some of the best preserved in Central America. Situated along Panama’s northeastern coast, the Kuna’s islands are frequently flooding due to severe storms and rising sea levels, forcing the Kuna to consider relocating entire communities to the mainland. Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra.

The Kuna General Congress – the group’s highest authority – delayed a vote on REDD+ more than three times. Doubts lingered about a few basic questions: who owned the Kuna’s carbon rights? Where would their carbon credits — their value in cash — end up? And perhaps most importantly: why would the Kuna need incentives to avoid deforestation when they had, in fact, preserved their forests so well without outside help?

“Some of our initial questions about REDD remain unanswered,” said General Congress spokesperson Bolívar López in 2009, while the indigenous leadership still struggled to come up with a final decision.

By June 2013, the General Congress finally, and emphatically, voted no. The move turned the Kuna into one of the first indigenous groups around the world to not only reject REDD+, but effectively stay out of the program and its promise of cash.

Meanwhile, the national coordinating body of Panama’s Indigenous Peoples (COONAPIP) has publicly accused the Panamanian government and the UN agencies behind the REDD+ effort of failing to properly consult indigenous groups in their decision-making and not offering enough financial support. A preliminary UN-REDD report based on an independent investigation has so far confirmed COONAPIP’s complaints.

A Kuna elder passes thatched-roof homes along the edge of Ustupu Island as he returns in his dugout canoe with buckets of landfill from his plot of land in the mainland forest. With parts of the island rapidly eroding due to flooding and rising sea levels, many families use landfill to keep the water at bay. Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra.

“The dialogue has failed both institutionally and personally, and apparently there is no confidence in the good faith of the parties involved,” the report says.

After much negotiation, COONAPIP agreed to keep working with Panama’s Environment Ministry and UN-REDD+ in December 2013. It’s still unclear, however, whether the accusations that REDD+ faced in Panama can be resolved in the longterm, or whether they could derail the program elsewhere. [Note 1]

The Kuna decision was resolute. And since their no vote, the community has emerged as a model of local, bottom-up conservation.

This spring, the elders of Ustupu Island held a conference for indigenous leaders from around the world on what they called “false solutions” to climate change, advocating instead for indigenous traditions of sustainability.

The Kuna’s mainland forest as seen from the air in July 2014. Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra.

Leave a Comment