The aims of the U.N. REDD (Reducing Emission from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) program diverge sharply from its chilling effects. Designed to compel governments in developing countries to reduce carbon emissions, REDD also aspires to engage with the interests of indigenous people. REDD claims to be “supporting the full and effective engagement of Indigenous Peoples and other forest dependent communities,” bringing it to odds with the fact that indigenous people across the world are rising up in vociferous opposition to REDD initiatives.

A U.N. program which uses financial incentives to encourage governments and companies to offset their CO2 emission by ‘conserving’ trees, its main objectives are to assist developing countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, whilst respecting the interests of all stakeholders. However, accusations have been made that REDD fulfils neither of these aims. Instead, it is said that REDD supports the activities of extractive industries and robs indigenous people of their land.

Meanwhile, the existing critiques of REDD are frequently muted by NGOs, corporative lobbies, governments, carbon traders, international financial institutions and the United Nations. For example, an Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) report that addressed the UN-REDD program’s failure to engage with local communities, was rejected by the World Bank on the grounds that the REDD scheme is “a widely accepted approach.”

The UN REDD program obscures the realities experienced by local communities through its representations to the public. They employ words with environmentally-friendly connotations to describe what includes environmentally-damaging activities. The UN REDD Programme Strategy explains that “REDD+ refers to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries; and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.” However, such written codes do not accord with their conduct.

Penetrating the jargon

According to a report published by a collection of eight environmental and indigenous rights organizations, REDD’s approach to reducing carbon emissions permits the planting of mass scale commercial forests. The report states that REDD allows commercial forestry on the condition that the corporations involved demonstrate that the new forests contain equal amounts of carbon to the previous forest; thereby, balancing out their carbon emissions. However, according to the report, this technique of ‘offsetting’ carbon emissions by planting (or replanting) trees is futile. Native forests and thus natural diversity is destroyed, species are put in danger of extinction and medicinal plants might never be discovered. Further, in the process, indigenous peoples are displaced from their ancestral land. Therefore, “enhancement of forest carbon stocks” can be translated as facilitating deforestation, displacing indigenous peoples, and replanting commercial forests.

REDD also allows logging ‘leakages’; companies are allowed to continue their activities as long as they remain external to conservation parks, says the report. For example, in Bolivia, loggers were forced off one area of land sectioned for conservation. Further, logging companies simply bought new areas of land elsewhere. Thus, the programme does not tackle the root causes of illegal logging but rather shifts it to other places, without leading to an overall decrease in extractive industrial activity. Therefore, “sustainability” can be interpreted as preserving one area of forest at the loss of another.

The conditions of the REDD scheme are contradictory to their stated objective of saving the climate and respecting indigenous rights. Firstly, REDD funding can aid governments and large conservation organizations to deny indigenous people basic rights to land and use of natural resources. Secondly, governments and organizations are only required to reduce deforestation rather than prevent it, whilst allowing industries to pollute the environment at unprecedented levels. By REDD’s standards, any reductions in deforestation makes further deforestation permissible in the future. When governments reduce deforestation by a certain amount, REDD allows them to balance this reduction with equivalent increases in later years.

Furthermore, only those countries actively participating in deforestation are eligible for funding, whereas countries with a good track record of environmental conservation receive nothing. So far the governments which have received funding include those of Cambodia, the Philippines, and the Solomon Islands. Such areas are infamous for excessive extractive activities resulting in habitat loss, deteriorating biodiversity, and soil erosion.

REDD and indigenous people

In furthering environmental degradation and facilitating new systems of ownership, REDD also endorses mass evictions of indigenous people, according to the report. With the support of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), indigenous people in Kenya were arrested and evicted from 21,000 hectares of land. On Brazil’s Atlantic coast, REDD is also permitting the destruction of lands inhabited by indigenous peoples, who REDD deny ever “owned” the land in the first place. One man was arrested and held at gun-point by government officials for cutting down trees to fix his mother’s house. In Panama, economic growth was at first privileged by REDD over the rights of indigenous peoples such as the Guna, Ngäbe, Buglé, Naso-Tjêrdi, Bribri, Emberá and Wounaan. When the National Coordinating Body of Indigenous Peoples in Panama (COONAPIP) voiced its concern for the encroachment onto their territories, a report was filed and REDD was forced to address indigenous concerns, an issue which they are still working on.

Whilst pressurizing activities can in some case force REDD to confront their short-fallings, “conservation” can still be translated as meaning forced eviction in order to make way for commercial forestry. REDD itself admits: “there is widespread concern that REDD+ activities may inappropriately impact Indigenous Peoples and local communities.” It is only in Panama, after external reports were filed, that the program has done anything to address these unintended effects, engaging in “extensive consultations” with indigenous people about how to improve their strategy.

Is REDD Neo-colonial?

The UN-REDD programme strategy also mentions that there are “trade-offs between forest management measures and vulnerable groups.” Countries where such trade-offs play out, where REDD has been exposed as incongruous with indigenous interests, include California, Indonesia, China, the Philippines, Panama, Ecuador, Kenya, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. This raises the question, are indigenous rights compatible with UN-REDD strategies?

Following a review of the problematic implementation of REDD in Panama, collaborators with PRISMA, (Salvadoran Research Program on Development and Environment) Nelson Cuellar et. al. suggest that REDD could still be successful when local views are taken into consideration and implemented at the sub-national level. However, the sub-national approach would not eliminate logging activities in the indigenous land. Furthermore, indigenous people have rejected REDD altogether. In April 2009, around 400 indigenous representatives signed the Anchorage (Alaska) Declaration, rejecting carbon trading and forest offsets as “false solutions to climate change.”

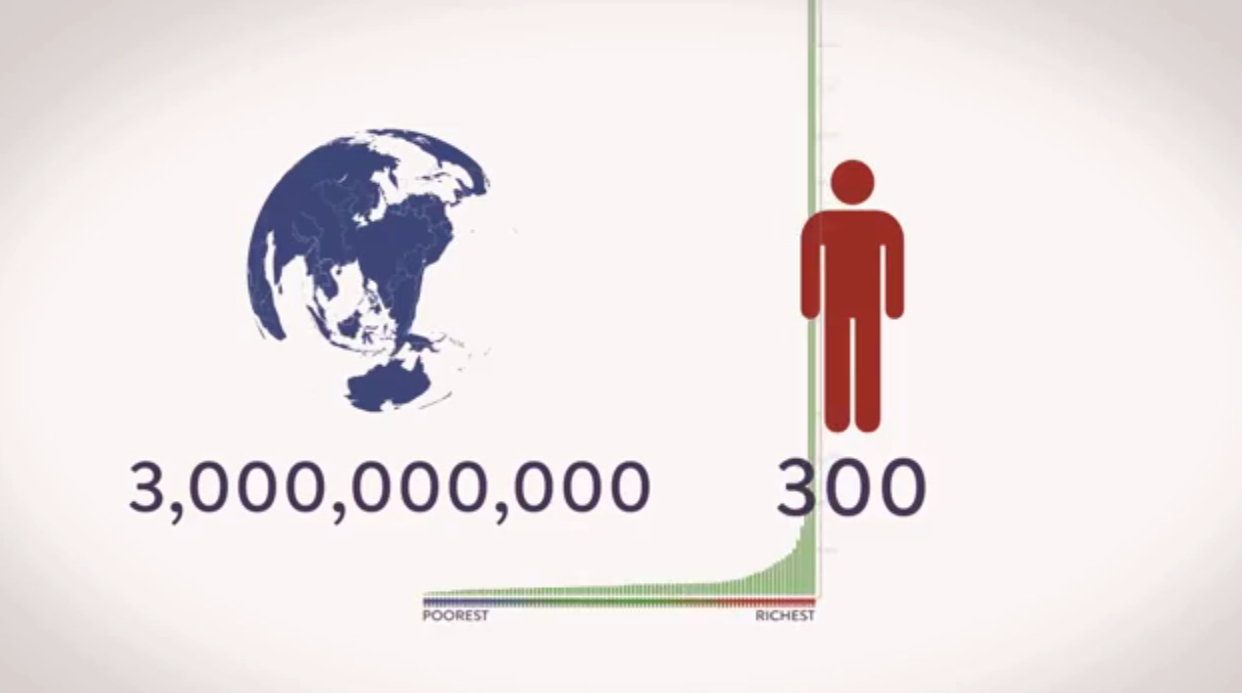

REDD has been described as “A new form of colonisation,” by Hector González, a lawyer for COONAPIP (the National Coordinating Body of Indigenous Peoples in Panama). His assertion is based on the fact that REDD forcefully grabs land from indigenous communities and concentrates the ownership of the world’s resources into the hands of a few corporations. This in turn denies the self-determination of developing countries and reinforces global inequalities. Indeed, international law of the likes of the UN-REDD Programme, have also been described as ‘neo-colonial’ by certain scholars. For example, according to the law Professor, Anthony Anghie, international organizations such as the UN presume that there to be a ‘natural’ order based on Western conceptions of ‘law.’ This becomes universalized as part as a civilizing mission which perceives any resistance by indigenous groups to be a violation of the ‘natural law.’

Developing a favourable climate strategy

Given the criticisms faced by REDD, if an environmentally sound and people-friendly scheme is to be developed, new rules should be put in place. In a discussion of the issues faced by REDD, Erin Myers Madeira, a specialist in indigenous rights and the role of forests in mitigating climate change, proposes some steps forward. Firstly, she asserts that REDD’s success depends on the prevention of deforestation and the protection of natural diversity. Further, the livelihoods of communities in forested regions in developing countries are always affected by REDD policies, and therefore, it is crucial that these stakeholders are directly involved in the planning and implementation of REDD programs.

Tom Goldtooth, and indigenous leader and Executive Director of the Indigenous Environmental Network, explains, “as “guardians” of Mother Earth, many indigenous tribal traditions believe that it is their historic responsibility to protect the sacredness of Mother Earth and to be defenders of the Circle of Life which includes biodiversity, forests, flora, fauna and all living species.” Therefore, Madeira notes that the success of REDD is absolutely contingent upon engagement with local communities, who are already conserving the environment via local means.

At present the UN REDD program neither reduces greenhouse gas emissions nor engages with local communities, which are its stated objectives. It encourages commercial logging and extractive industries, whilst displacing indigenous people off their ancestral lands. Martin Kirk is Campaign Director of the Rules, a global movement against inequality and poverty that are opposed to REDD. “From the perspective of The Rules…we believe [REDD] should be stopped. This is because…the pressure being put on the rainforests is ultimately driven by the demand for ‘resources’ to feed an insatiable economic system; a system that is incapable of being sensitive to how it has more than exhausted the sustainable limits of what the planet has to offer.” According to Kirk, the REDD policy is merely an unsustainable corollary of market logic; “neither economic growth nor market logic has a way of recognizing or processing things that do not have monetary value. If you believe this – which I certainly do – then it becomes entirely illogical to extend that logic to try and save one of the very few unexploited assets of the planet, which is the REDD formula. The only way to protect the rainforests in the long term is to protect them from the market, not feed them to it.”

Kirk and all those who have also joined the movement against this UN programme see REDD to be a solution that utilizes the same means that caused the problem in the first place and as Martin states, “don’t ask the market to fix a problem that the natural and correct operation of the market created.”