Written by: Nasim Beg

Introduction

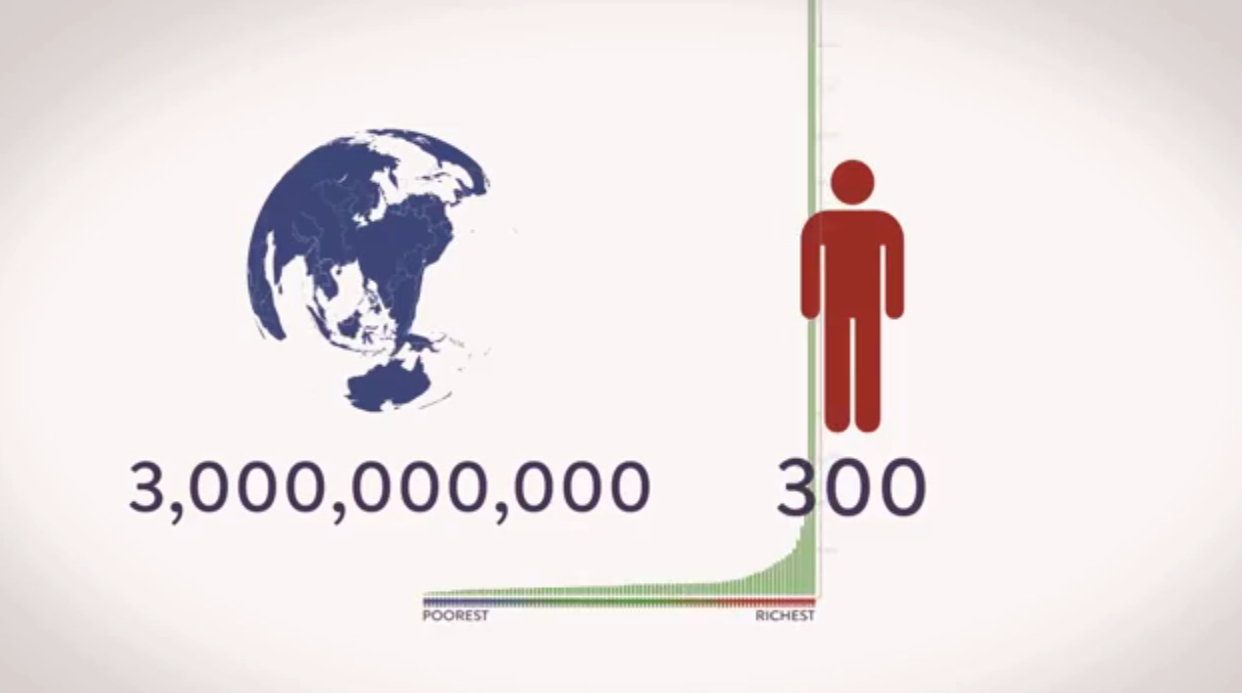

The issue of inequality is a profound one for contemporary societies, both developed and developing. Despite Friedman’s (1962) claim that improving business profitability is itself a major contribution to society – because social welfare increases when businesses make more money – a growing body of academics ranging from Jencks et al. (1979) to Stiglitz (2012) and more recently Piketty (2014) suggests that improvements in aggregate wealth may in fact be accompanied by increases in inequality. Certainly, increases in wealth are not always associated with prosperity for all. While rich societies do not always perform better on social and health indicators than moderately wealthy societies, more equal ones often do (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010).

This paper joins the debate on inequality by arguing that the ability of the powerful to borrow has been and continues to be a significant contributor to inequality.

We will argue that at the root of this predatory borrowing is the banking system in the form it is currently run and that it is supported very significantly by governmental behaviour in legitimising it.

Predatory borrowing through banks: The surplus that is produced by a society (savings) is stored in various forms; a significant portion of it is kept in the form of financial investments and in turn, for a large number of savers, the route to financial investments is the banking system.

Banks and businesses treat other peoples’ money or financial capital as their own, collecting the bulk of the rewards from the deployment on the premise that they are taking the corresponding risks; but, as we will try and show, in reality transferring the risk to the entire society. This reward-risk mismatch is reached through a legal fiction (having its origins in the Medici family’s invention of the double entry bookkeeping system dating back to the15th Century), under which, other people’s (depositor’s) money is treated as a “liability” by the Bank, and then this liability, or the same money, is turned around and treated as that Bank’s “asset”, with rights to a lion’s share of reward thereon. (It is not surprising that the Medici family became one of the most powerful and wealthy families of Europe). This inequity is further exacerbated by the bank in turn becoming a lender to a business and the business (equity) owner reaping the lion’s share of the reward; if the business fails, the bank and in turn the depositor (public) takes the knock, directly if the bank fails as and indirectly, by paying towards taxes if the business or the bank are considered too big to fail and are bailed out with tax-payers’ money, i.e., the public (depositor) is always participating in the risk.

It is this flawed aspect of how capitalism is practiced, that has for many centuries contributed towards the inequity in the financial system, i.e., not remunerating capital proportionally but using other people’s capital to enrich a few on the pretence of taking larger portion of the risk.

Leveraged and derivatives markets: Another form of borrowing, that cannot directly be attributed to bank borrowing, but contributes to inequality, is leveraging through the futures market: Banks are said to create money through fractional reserve banking but an extremely large amount of fictional money creation takes place through the futures markets, i.e., a free ride or what one may term as “free of cost and almost unlimited supply of capital” for trading of financial instruments like futures and derivatives. Quoting Bogle (2012) “These credit default swaps alone had a notional value of $33 trillion. Add to this total a slew of other derivatives, whose notional value as 2012 began totalled a cool $708 trillion. By contrast, for what it’s worth, the aggregate capitalization of world’s stock and bond markets is about $150 trillion.” The sheer magnitude of trading of these instruments places the entire financial system at risk (the market regulators may demand some margin so as to avoid failed settlements; they are unconcerned with the price bubbles being created and the central banks somehow feel that this non-bank money creation is not their area of regulation). These leveraged markets have throughout history caused price shocks, the price of which is paid by the public at large, while the few indulging in such transactions can walk off with abnormal gains. Again, creation of inequality at public cost through this form of borrowing.

The role of Government borrowing:

Government spending: When governments spend, they end up benefiting directly or indirectly some businesses (for example the defence industry, infrastructure contractors etc.). This aspect has been elaborated upon by Stiglitz. Many governments have been running deficits, thus it is the future taxpayer who will pay for creating opportunities for today’s businessman (and his heirs – “patrimonial capital”, Piketty). The irony is that the current voter does not suffer the pain of government borrowing or at least, not enough of it to react (and in fact may benefit from it through job creation), while the future taxpayer, who will feel the pain, will not be able to vote out the government of the past that had borrowed with the result (perhaps unintended) of the enrichment of a few. Thus, governmental borrowing, in a sense, disenfranchises the coming generations.

If the government were to meet the expenditure through tax and its other income (and not through borrowing), the present-day voter would vote out the government if taxed beyond the tipping point of endurance. In other words, if the voters feel that the expenditure being met out of the taxes is for the larger good, even if it benefits a few contractors, they would live with it. But where they feel that the amount of tax is going beyond their tipping point of endurance, they would react and that would act as a check on the undue enriching of the contractor. It is not difficult to imagine that the current day issue of “low voter turnout” would be very effectively addressed if governments could not borrow and had no choice but to tax. We are not trying to preach as to how best to practice democracy but are simply suggesting a mechanism that would act as a natural check on the growth of inequality though borrowing by governments (i.e., the populace reaching the tipping point of endurance if governments could only tax and not borrow).

A case in point of transferring the problem of repaying debt to the future (disenfranchised) voter, is the investment in nuclear energy facilities in Japan (a country with one of the highest levels of government debt to GDP); this “investment” made by the previous generation has to be paid for by the current and future shrinking population of Japan. Unfortunately, there are serious safety concerns today, which may call for a further financial burden whether they keep these going or decide to shut them down.

Borrowing caused inflation and its consequences: Borrowing by the government results in another very important aspect and that is inflation; this in turn has a dual impact on increasing inequality. The first is the fact that the already wealthy holding real assets will see the relative value of these assets go up, which will exacerbate inequality, as those with no or low value assets will become relatively less wealthy. The second aspect has a significantly higher and far reaching impact in creating inequality; millions of small savers are forced to seek preservation of the purchasing power of their savings and for most, the best avenue is perceived to be the safety of bank deposits or other fixed income investments. It is this very large pool of savings that is used by the powerful to become wealthier, while the savers, if they are lucky, at best preserve the purchasing power of their savings.

Should the government borrow? Each dollar a government spends, adds to inequality through some contractor benefiting from it and this seeds the capital referred to as patrimonial wealth by Piketty; worse still if it is a borrowed dollar. There is a large body of literature on how the powerful influence the ‘structure’ of governmental spending. See in particular Stiglitz’s work on asymmetry of information.

Many would argue that it is perfectly legitimate for governments to borrow and spend on infrastructure etc. that will benefit future generations. To our point of view, the right way to look it is that if we take a typical family, say an average set of parents, we would expect that they will strive to make and leave something for their children and perhaps their grandchildren, i.e., they would sacrifice and hold back on spending on themselves and create something for their future generation. The larger community is nothing but a collection of such families, thus one expects the larger community to act in the same way and collectively save and create something that the community feels would benefit the future generations. Like in the case of an individual family, the children are not expected to and do not pay for what their parents create even though they benefit from it.

Pension funds and life insurance: There is also another problem with government borrowing, when the government borrows, the pricing of the bond so issued is determined by the supply and demand at the time of the auction, (which may result at a lower effective interest rate than the expected inflation rate during its tenure); the pension or insurance fund manager’s primary concern is to match the long-term liabilities with bonds of similar life. Thus, whether or not the interest rate he locks-in, will compensate inflation is of no interest to him (his interest is not necessarily aligned with that of the ultimate beneficiary); he simply wants to have the ability to pay the contracted amount. This again results in transferring wealth from the public to the few who end up using the cheaper borrowing. Thus a very subtle mechanism is continuously in play transferring wealth from the weak to the powerful.

Capitalism and legal fiction: We are proponents of the free-market and are of the view that capital being invested deserves to and must be remunerated. However, the issue we have is with the fact that while remunerating capital, there is a flaw in the way “capitalism” is practiced. It is this flawed practice that has for many centuries contributed towards the inequity in the financial system and has been responsible for many of the shocks to the economy. It is not capitalism per se but using other people’s capital to enrich a few that is the issue.

There are numerous books and papers on the evils of lending; Graeber (2012) traces the history of predatory lending and the resultant creation of debt-slaves and puts across a wealth of well-researched arguments. The incompetence of central banks for encouraging excessive credit is the topic of “Greenspan’s Bubbles” (Fleckenstien & Sheehan 2008). However our focus is not on the lender but on the predatory capture of the system by the powerful borrower and debt being used by the powerful as a tool directly and indirectly (direct borrowing and leverage through the market; and indirectly through funds borrowed by the government), to further empower themselves at the cost of the public.

Irrespective of how banking has emerged and evolved, in today’s world it is almost entirely dependent on governments. It is not merely the perceived invincibility of banks (as ultimately governments step in, to bail out banks) but more importantly, the fact that government actions (borrowing and running deficits) cause loss of purchasing power of the paper currency issued by the governments (or their central banks); this in turn causes savers to try and preserve the purchasing power of their savings by seeking (safe) fixed income returns (primarily from banks).

And, as long as banks keep attracting deposits, they can help governments borrow further by using the depositor’s money to invest in (risk free) government debt. This virtuous cycle from the government’s and the banker’s point of view has become a self-sustaining system, while it constantly contributes towards inequality.

Small savings and the financial system further empower the powerful

A significant portion of public savings are kept in the form of financial investments. These financial investments are assumed to be best deployed in a free market based capitalist system. While there is a substantive academic work critical of the free market and the capitalist system, we do not join that wider debate but take issue with the capture of the free markets by the powerful, such that the markets no longer remain free. The powerful in the market manage to capture the average citizen’s financial capital and not only usurp the investment rewards thereon but expose the average citizen to extreme financial risks.

The average (financially not very informed) person’s savings are not a commodity and, therefore logically, must not be treated as such in a free market. Governments appear reluctant to intervene in this regard and thus fail to perform their fundamental duty of protecting the savings of the individuals from being treated as a free market commodity. The argument put forward in support of this approach of non-intervention revolves around the concept of “moral hazard” that is involved in influencing the direction of the placements of such savings. There is also an associated argument of the fundamental freedom of right of individuals; the argument is perceived to allow individual owners of the savings to deal with these as they please; a freedom of choice.

We see the reiteration of freedom of choice in this area, to fall under the framework of rubric of freedoms that are denied to individuals for their own good and also for the good of society through a collective choice. The denial of this freedom can be seen on the analogy of somebody putting up a faulty argument that suicide should be legally allowed or that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US should have no role to play in allowing availability of drugs; and whether the FDA should be allowed to infringe on the fundamental rights of freedom of choice of the individuals to take whatever drugs they wish to.

Public interest is at stake when the weak are almost forced to keep their savings with banks.

This concept of a bank taking the small savers’ money and giving it the legal cover of treating it as a liability in its books allows the bank to then put the money (as well multiples thereof through fractional reserve banking) at risk and earn and retain the gains on the basis that the banks are taking the risk. In fact the bank manager puts the depositors’ money to risk and shares the reward with the owner of the bank and thus justifies his commissions or bonuses. The bailout history of banks by respective governments the world over, has given the banks the perception of almost invincibility, which translates into monopolistic power. This helps the banks keep other options for small saver out of his reach.

The existing structure is built on a fundamentally unfair legal trickery whereby the average saver remains at risk but under-rewarded. This fiction is further exacerbated by the bank then becoming a lender to a business and the business equity owner reaping the lion’s share of the reward; however, if the business fails, the bank and in turn the depositor (public) takes the knock.

Graeber (2012) quotes Lord Josiah C. Stamp (Albeit, he cautions that this may not be an accurate quote) “if you wish to remain slaves of Bankers, and pay the cost of your own slavery, let them continue to create deposits.”

The impact of the free market is even greater in the entire area of the futures markets; irrespective of the fact whether the transactions made, are over-the-counter bilateral transactions or these transactions have been undertaken through some organised exchanges. This phenomenon is far more abusive as compared with creation of fictional assets by the Banks; the entire structure is built on “free capital” allowing a few to make highly magnified gains through exaggerated sized transactions, employing at best, a small fraction of the capital relative to the size of the transaction. The price bubbles which are logically and invariably caused by this creation of fictional money that comes from nowhere, but end up creating stress for the entire financial system, i.e., this money is a creation of the system, a structure owned by society (public at large), the public takes the risks (pays the price) but does not share the returns, while a few players benefit from the money so created. The fact is that the entire communities are at “equal risk” when economies go through the inevitable, leverage caused prolonged down cycles. Thus, the small saver effectively participates in equal risk but is the lesser equal in terms of reward. Such practices allow a few people to enrich themselves using other people’s resources, particularly financial capital (and the system created money) and are the roots of creating inequalities in the society.

The financial structures that we presently accept as granted, also include flawed taxation laws in terms of how return on (or the cost of) capital is taxed in most jurisdictions. The prevalent tax laws favour financing of businesses by using borrowed capital (the low-risk savers’ money), which results in a significant tax advantage for the equity investor (the so called high-risk capital), as the portion of the business earning that is passed on to the debt capital provider (depositor) is treated as a tax deductible expense. However, in times of stress, the businesses benefit directly or indirectly through government intervention at public expense (taxpayers who include the same small savers). Thus taking it net of tax, an even higher portion of the earnings flow to a few at the cost of the public, i.e., contributing further to inequality.

An example of how transfer of wealth takes place at two stages using the small savers’ capital and ending up enriching a few.

Piketty (Capital in the Twenty-First Century) has demonstrated that the head-start one gets with inherited (patrimonial) capital will add to divergence in wealth as compared to what wage earners (labour) can accumulate.

The wage earners (and if we include a broader collection of all middle income and low income earners – not necessarily strictly labour) have, over a good part of the Twentieth Century and leading into the Twenty-First, been saving and investing their capital in financial avenues, starting with basic bank deposits, followed by fixed income instruments and thereafter, depending on the country and the development of its capital market, some in equity. These savings are a part of the ‘capital’ in Piketty’s data analysis.

Piketty demonstrates the inevitable capital accumulation and divergence where “R” is greater than “G” (i.e., the rate of Return on capital is greater that the Growth rate, which in turn reflects the income that flows to labour). The fact is that the distribution of “R” is heavily and unfairly skewed in favour of the predatory borrower by paying the lender (average depositor) a pittance (and nothing, rather a cost if the borrower uses the leveraged futures market) and on top of that, he gets a tax break; and that is not the only benefit at the tax payers cost, as if the government borrows (which the future taxpayer will repay), the predatory borrower gets more contracts (business) to borrow for.

We are presenting an example of two US corporations, Walmart and AT&T, with their last five-years (to 2013) income distribution amongst Equity holders, Debt providers and the Government (tax). We have then carried out a quick calculation indicating the distribution if there was no commercial debt and that the entire capital (including that supplied by the debt provider) was equity, (second pie chart):

The benefit to the borrower (and conversely the depravation of the risk-averse debt provider) is obvious from the above. We do not at this stage have data on how much of the debt is directly from the average weak investor and how much of it through banks. However, if the average weak investor has invested through a bank, the illustration on Wells Fargo’s income distribution indicates the second level of depravation. The first pie chart below indicates the distribution on how the system currently works and the second one on the assumption that all capital (including the depositors’ money) was equity:

In the example of the two corporations (Walmart and AT&T), the weak investor loses out almost 50% share of income distribution; and if he has invested through the bank, such investor would take a further cut of 60%. Thus the share of return on capital saved and invested by the weak investor is approximately 40% of 50% i.e., 20%; conversely in such a situation, up to 80% of what should be the share of business income on the Capital contributed by “labour” goes to the powerful.

The increased share of distribution to the original debt provider (if all capital became equity), may not make a very significant difference when distributed on per capita basis over thousands or millions of debt providers (depositors); but on the converse side, the undue gain that is concentrated amongst a relatively small group of equity holders (especially a few very large ones), will make a significant difference to their share of income. It is this mechanism that contributes significantly towards inequality in the distribution within “R”.

We must clarify that these examples of the last five-years corporate and bank results, do not reflect that fact that there can be periods of losses when the reverse position can be true but there is enough published empirical evidence to show that over the long term, taking the all businesses in to account, equity owners have come out ahead. Thus the generality of the argument is valid.

Free market and financial transactions: There is also an issue with the interpretation of the puritan concept of free markets; “free market” is at times erroneously taken as carte blanche or as “freedom to exploit”. Free market to us means efficient allocation of capital, where informed choice is exercised but it does not mean freedom to make predatory attacks on the savings of the weak (and financially not well informed). The real risk is and should be that of one’s savings being exposed to the performance of the economy and businesses within that; the risk or reward should not be from getting the better of a fellow community member.

The “free market” as it operates, also allows for creation of “free capital” for trading of financial instruments like futures and derivatives. These highly leveraged markets tend to cause price shocks, the price of which is paid by the public at large, while the few indulging in such transactions can walk off with abnormal gains.

Central banks (the typical custodians of printing and creating money) have constantly shied away from addressing the matter of credit and asset-price bubble creation by non-bank entities through fictional money. The market regulators concern themselves only with trying to ensure that there are adequate margins in place to avoid failed settlements; they seldom concern themselves with the price bubbles being created and the consequences thereof.

Investments are pushed into high-risk zones:

Equity Investing: Markets are dynamic and multifaceted therefore, it is not possible to apply one single formula to fit all times and all aspects of it. The concept of free market also, like any other ideology, has its limitations and it cannot be applied to every aspect of the financial market or even one formula is applicable across the entire spectrum of a single asset class. Equity markets form one component and it is not suggested that within the equity class, we should not differentiate between classes of risk, e.g., one may choose to invest in a start-up or a mature business or one that is likely to have a stable income or one that is engaged in cyclical business where the earnings may be volatile. Similarly, investing in different geographies and in different companies within each category will justifiably carry differing risk and reward. If we take investments in the equity asset class, the underlying risk of equity investments is that the venture may fail but this risk is exacerbated, firstly by the business venture borrowing and not being able to survive stressful times (due to the burden of having to service debt) and secondly, the price volatility of its share magnified by leverage (margin purchases, short selling, futures contracts etc., bought and sold for exchange of small sums of money but representing large underlying volumes). Investing in equity has this magnified risk at two levels, thus the small saver is encouraged and at worst forced to take the perceived lower risk route (supposedly exercising free choice) of keeping the money in a bank deposit. We happily accept this situation as the conventional wisdom is that an ill-informed investment decision by a small saver can push such saver into destitution and such investor is best off playing it safe.

Corporate Debt: Similarly, corporate debt instruments have assumed great complexity over time, while simultaneously the credit rating system has become more unreliable. These issues can be too complex for an average investor to understand. Many small savers find it difficult to understand the inverse relationship between the security price and interest rates. This aspect again pushes the savers to store their money with banks. In any event, a corporate entity borrowing the small saver’s money will have the same impact as the bank taking a deposit – the equity investor gets an undue share of the cream but the debt provider suffers if the business is run into the ground. The existing structure of differentiating between different classes of capital is inequitable and adds to inequality.

Commodities: The unfettered ability of the leveraged ‘free market” to distort the pricing mechanisms in physical (real) commodity market is a subject in itself. Price equilibrium on the basis of the real supply and demand of the underlying commodity is at times different to that created on account of an exaggerated perception of the same through financial leveraging in futures trading. The price volatility (through exaggerated perception of leverage-multiplied supply and demand) makes investing in the underlying asset classes more risky than what the underlying fundamentals warrant; thus it appears best to avoid such asset classes and stick to the “safe” bank deposits.

Is there a solution?

The question that arises here in this context is whether society should allow the banks (and other functionally similar entities) to take public savings as deposits (liabilities), put these to risk and pocket the lion’s share of the reward on the pretence that it is they who are taking the risk and have adequately compensated the depositor; while in practical terms the depositors, the real owners of the capital invested in the business, virtually receive a very small portion of profit.

Apart from banks not being able to draw a legal wall between depositors’ money and their own, they should not for similar reasoning, give this money out to businesses as loans and be treated as non-owners of the business capital contributed by them through a similar legal wall.

The next question is whether corporates should be able to borrow from the wealthy (either directly or through investment banks etc.): if small savers’ money was taken only as equity and debt becomes relatively scarce, the wealthy would be in a position to get unfair terms with senior rights on the assets of the business, it could include preferred stock with senior rights over the profits and the assets of the business. Unless all capital employed in a business is treated at par, that supplied by the weak can and will be at higher risk but not reward. There is another legal concept of “limited liability” which prevents the small saver from recovering his savings (through the bank of course) from the immunised assets of the powerful. Immunising equity capital providers has helped businesses attract capital, this in itself is not wrong but when combined with differentiation between debt and equity capital, the structure contributes towards inequality.

There are similar financial institutions other than the banks; like the life insurance companies, home finance institutions and pension funds that work on same basis and treat the savers’ money as a liability. All of these play a role in the skewed distribution of “R”.

The questions that need to be addressed, if there was no commercial borrowing:

Based on how we are currently used to running businesses, we are able to have some permanent capital (equity) and a combination of short and long-term borrowing as well as preference shares, which can be converted into equity or can be redeemed with various innovative options.

In a “no-liability” world, banks would need a great deal of innovation to evolve an efficient system, which would treat all funding as equity.

We would need a mechanism, which would allow a business to take in new equity, return some of it from time to time when it has surplus cash; and then, as and when it requires cash again, get new equity.

This, on the face of it sounds quite daunting and more so if the business is not listed and we cannot resort to a market mechanism for determining the price of the new equity injections or buy-backs. Market based price discovery is something all of us accept as fair, however, this too has flaws in that, the price put on a business by the market can vary very significantly within short periods of time.

Looking Ahead

If one were to assume that government and commercial borrowing were outlawed, it would be beyond any one person’s ability to forecast as to how governments, financial institutions, businesses in general and people at large would deal with the situation. The current structures have evolved over several centuries, thus any new structures under a paradigm shift of the financial system would require considerable time to evolve and the transition would certainly be challenging. Nevertheless, one can try and raise some of the most obvious questions that will need to be addressed.

Business Capital: Assuming all money saved and invested by the public (bank deposits, insurance, pension contributions etc.,) is not treated as a liability but as investment in collective investment pools, thus at equal rank (pari passu) with all other investment in the pool; the pool in turn would invest in individual business opportunities on a similar (equal rank) basis.

As stated earlier, most business entities need some, what one might term as, permanent or long-term capital and some shorter term; the need of which can vary from time to time – whether due to seasonal, trade-cycles or other reasons. In addition, businesses also need, what are termed as, non-funded financing arrangements (e.g. performance bonds, letters of credit etc.).

Under the present financial system, business firms are able to acquire these various types of financing, unique to their needs, through direct investors, banks, intermediaries and the financial market. A simplistic alternate would be for the firm to have a large amount of permanent capital (equity), which would cater to all such needs. This would obviously leave varying amounts of idle capital from time to time; clearly highly inefficient and unacceptable.

It is difficult to imagine as to how an efficient system would evolve when we are so used to our present system; though, one might add, the present system has evolved over centuries. We have two broad classes of funding available to businesses, equity and debt (including non-funded facilities which can potentially convert into debt); the beauty of debt from the business entity’s perspective is that it is efficient (the business borrows exactly what it needs), it is relatively low cost (albeit at the cost of the public) and on top of that, tax efficient (also at the cost of the public).

Hedging transactions: At times businesses need to hedge against certain types of risk, usually in the case of mismatch in timing of two aspects of a transaction. If we were to restrict hedging transactions to a non-leveraged basis, the creation of price bubbles and the related disasters would be avoided. On the other hand, the business entity would need to block funds earlier than it would need to under the present system, thus entailing inefficiency. The choice is to have relative inefficiency from blockage of capital or to expose the system to the consequences of bubble bursts and depriving the leveraged speculator from excess profits obtained at the cost of the system (public).

Business Credit: In their normal course, firms can procure inputs (goods and services) on credit and in turn, they need to allow credit to their customers. This is not the lending or borrowing that creates transfer of wealth from the weak to the more powerful. The issue here would be that the business would need the working capital so required in the form of equity; and if some portion of it is needed for a short term, the provider of such capital would need fair remuneration; not the fixed rate compensation structure but a fair return on the value added to the business through provision of such sort-term equity. Banks and financial institutions will need to develop the ability to do so.

A new world for banks: Would the banks, in their new role, if debt were outlawed, be able to develop mechanisms that will cater to permanent and short-term equity? As well as the ability to provide the non-funded facilities but without taking on any possibility of that converting into debt? The answer has to be “yes”; human beings (and especially bankers) are innovative and find ways and means of going forward.

Not only would the banks have to find a way of dealing with the cash management aspect of the businesses they provide funds to but would also have to cater to the cash flow needs of the depositors (equity investors in our new scheme of things). This would again tend to be inefficient, as the banks would have to carry some un-invested funds to meet the unplanned cash-flow needs of the depositors.

A big challenge would be for banks to work out acceptable valuation mechanisms of the movement, in and out, of the capital (equity, whether of permanent or temporary nature). The current norm of accepting a market based pricing is accepted by us blindly (the market is always considered right) but as mentioned earlier in this paper, the market can be extremely flawed, the price of a stock can halve or double and then go back to half within a period of a year, we have seen that happen to the stock of a company like Apple.

In dealing with this challenge, banks would have to go back to the basics, i.e., have a thorough and on-going knowledge and assessment of the business they are invested in. This can only be viewed as something positive, as opposed to the tendency of moving towards programme lending and the use of mathematical probability of success or failure rather than knowing and understanding the business entity and its type of business.

The bigger challenge would be that the banks would not have a lifeline available, i.e., there will be no lender of last resort. This would mean that there will be two distinct types of deposits, those that can be withdrawn at any time and those that would be locked in as equity investments (whether long-term or short-term); the former deposits would naturally not be entitled to any remuneration (in fact, the bank would be in its right to impose a fair charge for safe custody of that money); and the latter not eligible for withdrawal on demand but entitled to proportionate share of profit (or suffer loss at times). If we assume that the government and businesses do not borrow, the economy would be far less prone to inflation – one major cause of inflation, i.e., excessive money supply, would be absent. Thus storing money to meet short-term needs as a non-remunerative deposit with a bank would be feasible, with the bank providing the modern-day conveniences (cheque issuing arrangements, debit cards, ATMs, on-line transfers etc.) for a fair fee. Such cash would not earn a return nor would the bank turn around and invest it with any business entity.

In the commercial debt-based world, a bank has to maintain certain level of capital to mitigate systemic risk; Basel type protocols have evolved, which attempt to achieve some minimum standards universally. However, in our hypothetical world, the comfort would come from ensuring that the bank’s capital (some minimum ratio) is co-invested with that of the depositors and ranks pari passu with the depositors’ funds.

Consumer finance: Product Suppliers benefit from increased sales if their customers have access to financing. If business houses wish to sell on credit, they can fund specialised structures for this. This is what some businesses like automobile companies already have in place (albeit not based on their own but borrowed capital, which would need to change).

The issue of inefficiencies resulting from requiring equity for all aspects of business

There would be a strong argument against the “all equity” world of doing business in terms of the inefficient allocation of money available in the system especially through the tying up of large amounts of idle capital. To look at it in another way, when, under the current manner of doing business, a firm does not require certain amount of borrowed cash, it returns it to the bank; the bank in turn can allow some other firm to use it, thus the likelihood is that the capital in the system will remain deployed most of the time. If this money remains idle and on top of that a firm has to block the full value in cash against a non-funded facility provided by its bank, it would cause a further drain on the business capital in the system. This is bound to slow down business growth. This issue is real, in that the total quantum of savings (capital) in the system does get a multiplier effect through fractional reserve banking and firms are able to get banks to stand behind their commitments based on the firm’s credit standing with the bank (at times with a fraction of the commitment amount deposited as margin with the bank). The bank relies on the firm’s standing or a combination of the standing and some margin deposit against the possibility of the non-funded commitment converting into a forced loan. In the “no loans” world, the bank would have to rely on having the full amount on deposit.

All of this is likely to translate in a higher demand for business capital (all of it equity) but on the other hand, a much lower risk of failure of individual businesses and less volatile business cycles. At an individual stock level, it would mean lower price volatility but probably a higher impact cost (moving the price adversely at the level of each transaction). This would also mean a lower return on equity but the correct way to look it is that, it would translate to reduced inequality and a better return on the very significant portion of the capital in the system that currently gets a meagre return (i.e., result in a fairer distribution).

The non-business borrower

Home Mortgages If banks were only providing equity capital for businesses and were no longer in the lending business; it would be for the governments to decide if they deem it prudent and socially necessary, to cater to mortgage finance perhaps for the lower and middle-income families; this would need to be organised through creation of a revolving pool or a sort of trust fund by funding it through tax collection. If the government organises such funding, the pool would ultimately become self-sustaining through recoveries and would need minimal replenishment through on-going taxation. (This would of course depend on the demographics of a particular society). A point that needs to be recognised is that unless the rate of interest applied on the mortgage loan equates the rate of change in the underlying property value, it will result in transfer of wealth.

Student loans An important role is played by the society (philanthropy) for supporting students through higher education but governments can also provide the financial resources (again, funding this through tax collection), ideally through community organisations. This would require society to pay for the student loans through taxes but like the example given for home mortgages, the pool (depending on demographics) should become self-sustaining over time. With the involvement of the community in disbursement and oversight over recovery, the student taking the loan is likely to act very responsibly.

Credit cards This is one aspect that would make funds for consumer credit scarce (as banks using depositors’ money would not be in this space and even if such lending is banned, we may still have some undocumented loan sharking); credit card type borrowing is a typical example of consuming now and paying for it later, which is likely to lead the person into a debt trap. Predatory lending is not the focus of this paper but a matter, which has been the bane of society throughout history. However, the more damaging, society-wide consequence is that consumption based on borrowing is not sustainable and leads to excess capacity and job creation in areas that cannot be sustained, for which the society (and on many occasions the next generation) ultimately pays a cost. In the meanwhile, a few business owners become wealthier and as demonstrated by Piketty, the wealth is carried forward adding to inequality.

Issues that investors would face

Life Insurance The insurance industry has evolved on two distinct structures, i.e., the (more predominant) insurance company structure and (the lesser developed), mutual insurance structure; the former is where the company underwrites the risk and seeks a reward (in terms of collecting more insurance premium than the expected pay-out against claims), the latter is more akin to the community collectively contributing towards the losses suffered by some of its members (the per head cost being equivalent to the premium but without a potential profit for the company). The mutual insurance format is more important from the point of view of life insurance and annuities as, very importantly, the asset-liability matching decision in the case of the company structure is indifferent to what the beneficiary achieves in terms of inflation protection. In other words, inequality is being fed if the beneficiary’s life insurance pay-out does not cover inflation and leads to the beneficiary into poverty, while someone else reaps the benefit at the beneficiary’s cost.

A Pension Funds Pension funds, would again have to be run as collective pools and be invested in a combination of cash and equity of a broad range of companies, i.e., the economy itself; if the economy does well over the working life of an individual and continues so during the retirement period of the beneficiary, he or she will do well, obviously the converse being true too. The government would need to provide for a safety-net by raising funds through taxation and keeping a reserve aside.

The Saver’s interest: In the world this paper has described, where all investments are treated as equity, the average bank depositor would not be able to get his or her money back on demand, unless the bank were to keep some un-invested cash, however, the bank would not have the same convenience as it currently has of being rescued (for emergency cash needs) by the lender of the last resort (the central bank lending typically against government securities). This would imply that such cash remains uninvested and the depositor does not get remunerated.

The Macro implications of governments not borrowing:

There would be no deficit finance whatsoever and infrastructure development would have to be funded by raising taxes, i.e., the current generation would save and invest for the future generation.

Economic growth would not see an accelerated pace based on borrowing. The misapplied and wrongly labelled “Keynesian” balancing act would not be attempted by running deficits but one would resort to the biblical guidance of saving up during the seven good years to mitigate the lean ones.

Catastrophes would have to be funded through taxes raised within a country and at times internationally.

Conclusion

If we eliminate borrowing by the government, which infringes on the right of the taxpayer to vote out the government that effectively imposes the tax, we would remove a significant element of government spending that enriches a few (and their heirs) at the cost of the future taxpayer. This would also mean that the same future taxpayer would not have his job stolen through borrowings by the past governments. On top of this, the economy is likely to be relatively stable, as monetary policy driven economic cycles would be eliminated; an overall better deal for the average citizen and reduced inequality.

Eliminating governmental borrowing would also remove the inflation caused by such borrowing and in turn enable savers to move away from banking as we know it. If we move to an economic structure where businesses do not borrow but treat all capital as equity and all future settlement (hedging type) transactions are supported with full amount of cash, the likelihood is that the we would eliminate the uneven reward from investing in businesses and remove the “heads I win, tails you lose” reward from speculating with the system’s (public’s) money, which invariably ends up in the public paying the cost when the bubble bursts.

The risk of investing in equity would be reduced, therefore likely to draw in a significantly larger amount of the average citizen’s savings (with proportionate reward flowing to the average saver) and with the government not borrowing, a significantly reduced risk of economic cycles (reduced risk for businesses and the equity investor); and for those who do not wish to or cannot take equity risk, the choice of keeping their savings in a more stable currency, not losing its purchasing power due to credit and deficit driven inflation.

Doing away with government and commercial borrowing are likely to result in a more equitable society (including intergenerational equity), with a relatively stable economic environment (reduce the inequality causing volatility), albeit with lower (but more normalised) growth rates.

REFERENCES

Bogle, John C. 2012. The Clash of the Cultures: Investment vs. Speculation, John Wiley and Sons

Fleckenstein W. & Sheehan F. 2008. Greenspan’s Bubbles: The Age of Ignorance at the Federal Reserve, McGraw-Hill

Friedman M. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press

Graeber, David. 2012. Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Melville House

Jencks, Christopher. 1979 Who Gets Ahead?: The Determinants of Economic Success in America, Basic Books

Piketty, T. 2014, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Stiglitz, J. 2012. The Price of Inequality. New York: Norton & Co.

Wilkinson, R. and K. Pickett, 2009. The Spirit Level, Allen Lane.

Acknowledgements

Beg, Mirza Qamar

Kirkham, John W.

Khan, Muhammed Jehanzaib

Munir, Kamal

Sherani, Sakib

Yazdani, S. Gulrez

This article was my introduction to therulesblog.wpengine.com and for that I am grateful. Where it is proposed that governments should not be allowed to borrow and meet expenditures primarily through taxation, I was almost afraid to read further. Afraid, because while it seems revolutionary and disruptive, most of us know in our hearts that you can only kick the can so much further down, before you run out of road. Fortunately, I persisted and the prescriptions suggested in the article make their case in both economic and social justice terms. Mr. Beg has outlined for us a grail quest, and if in our lifetimes we can affect only a fraction of these changes, there is hope for a financial Camelot.

If we have to get too the root of it and reduce inequality, while staying with a market based resource allocation system, we as a world community, must agitate against the system of borrowing by governments and the powerful

Thanks for this thought provoking discussion Beg sb. I don’t think I am qualified to add much but would like to share some experience I have had with long term savers.

Long term savers such as pension funds and life companies remain probably the biggest investors in government debt. Maybe, just maybe equity investment would have saved the many closed defined benefit pension schemes but the defined contribution schemes continue to invest in debt which barely earn inflation.

So if we can change how ‘deficits’ are measured in pension schemes maybe we can reduce demand for bonds and then bonds will return more.

Given the long duration of pension schemes we should not have to measure deficits on an annual basis anyway as this appears to ‘create’ volatility which effectively shortens the horizon for pension schemes and takes away their duration advantage. This is the classical time diversification argument but does it really exist?

Sadly not according to many academic studies such as this one: http://merage.uci.edu/~jorion/papers/risk.pdf

So maybe if we can find evidence for mean reversion in equity returns (which academics don’t believe in) or an increasing term structure for equity risk premium we can probably reduce demand for bonds and hence rationalise bond returns. I don’t think it is going to be easy though!

Faisal, thank you for your considered comments. The empirical evidence may help the proposition somewhat. Regrettably, there is no country or market where the volatility in the equity asset class returns is not adversely impacted by the existence of the debt “asset” class. Having said so, one may be able to run the equity returns analysis for different countries, while plotting alongwith that, the quantum of debt impacting that economy. I use the words “debt impacting the economy” rather than the “debt in the economy” quite deliberately, as most of us end up using US data, where the true debt gets fudged due to the holding of US treasury bills by China and other nations. I haven’t attempted it but I feel that analysing equity or for that matter real estate returns over the long run and the volatility affecting these, need to be adjusted for the quantum of debt impacting these over that period (as well as some time preceding it and following that period – the impact of a debt caused bubble preceding the selected period is obvious but the anticipated contraction – like the expected end of QE, does impact these returns too.

Mark Twain held that “Bankers are those who lend you the umbrella when the sun shines and want it back when it rains” and you can’t really blame them for that.

But when bank regulators introduced risk weighted capital requirements for banks… more clearly described as portfolio-invariant-credit-risk-weighted-equity requirements for banks, then they made sure bankers would lend you even more willingly the umbrella when the sun shined, and want it back even faster as soon as it looked like it could rain… and you can really blame regulators for that.

Layering on one risk-adverseness upon another only guarantees a very dangerous excessive risk aversion.

http://subprimeregulations.blogspot.com/2015/03/current-credit-risk-weighted-capital.html

Mr. Kurwoski, your note on the risk weighting against perceived risk is absolutely the issue through which Basel is driving and causing a circular problem.

My issue is not with the lending but the unfair borrowing and paying a pittance of the return on the basis of the perceived lower risk taken by the depositor. I find this premise flawed for reasons put forth in the paper above.On top of that the borrowing by governments makes matters worse. We will continue to struggle, unless we change the underlying structure of differentiating between debt and equity. As you would observe, my issue is with the inequality being caused by the capitalist system as practiced today. It is not capitalism per se but using other people’s capital to enrich a few that is the issue.

Hello Nasim,

Thank you for this thoughtful and carefully prepared article. I am the research director here at TheRules.org and also co-founder of Economics.com where we are working to provide the scientific basis of sound economic thinking (informed by evolutionary studies and complexity science). An article I co-authored with David Sloan Wilson and Robert Kadar offers additional support to what you are saying here — with the additional clarity that evolutionary theory can bring in the form of “multi-level selection” as the mechanism for why self-interest undermines society in many circumstances.

Our article was just republished here at TheRules:

http://therulesblog.wpengine.com/we-need-a-new-economic-paradigm-for-the-society-as-a-whole/

I would love to hear your thoughts about it. Very much appreciated what you’ve offered our community with your writings so far.

Very best,

Joe

Uh-oh, the auto correct function on my computer changed the text for our Evonomics project!

😉

The link can be found here: http://www.evonomics.com

Joe

Thought you would find this persistence and survival of wealth interesting:

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2016/05/19/the-wealthy-in-florence-today-are-the-same-families-as-600-years-ago/

Best

Nasim

Hi Joe,

Thank you for your encouraging note and for drawing my attention to multi-level selection, an area of research I was unaware of. I have now read up a bit about it and find it facinating. I have always wondered if the world can ever evolve to a common planet for everyone or whether mankind is destined to remaining a set of groups within groups and at the end, an us versus them world. Intuitively, the latter appears more probable. I would love to see scientific support applied to my thoughts and I look forward to a continuing interaction with you.

Kind regards

Nasim

This is an excellent and a thought provoking essay. One of the best readings in a long time. I don’t think that I can add anything new here, but can certainly share some thoughts that reiterate the same points that you have mentioned.

I cannot agree more with some of the analysis above, in particular, around the inflating asset prices and widening economic inequality within the society. One recent example is not far from home, property prices in world capitals, London, New York, Mumbai, Hong Kong, and others, have increased to such levels that the rental yields have plummeted below 2.5% in some areas. In London, the leveraged buy-to-let investment is one of the major reasons for the sharp increase in property prices, which have become well out of reach for an average individual. The number of landlords is sharply increasing and so is the number of individuals renting (as opposed to owning) a property. This is a classic case where cheap lending rates have artificially inflated the asset prices and increased the risk to bank deposits (which fund these mortgages). The cash savers, as pointed out in your essay, have paid for their own slavery, as the inflating house prices are now ever more expensive (relative to their bank deposits), and worst of all, when the music stops (ie the bubble bursts), these depositors risk losing their bank deposits. The number of people owning multiple properties is rising and so is the number of individuals renting – evidencing the polarisation of the economic wellbeing within the society.

The pension funds and insurance companies, as you point out, are still hedging the fixed rates despite the historic low yields on fixed rate assets, pushing their prices further up (and yields further down). Governments are borrowing at record low rates in hope of reviving the economy by encouraging spending rather than saving. But it hasn’t all worked out as planned. Inflation is still well below the government’s target, threatening recovery and survival of many businesses and jobs – but equity and property markets have entered into an almost bubble territory. In 2006, asset prices were high because earnings and employment were high (coupled with extreme levels of leveraging). In 2015, asset prices are high because rates are low (with little evidence of net deleveraging of the financial system). The wealthier few have benefitted from the low rates to leverage their investment portfolios, whereas the less fortunate ones have become more risk averse (in the deteriorating economy), and in doing so have unconsciously handed their cash savings to their wealthier counterparts to gamble. The leveraged investor is long risk and earns a premium only when he makes more than the cost of borrowing, whereas the cash saver risks losing out if risks are excessively high. This non-alignment of interests almost always works against the cash saver, as the “control of the money” is in the hands of the borrower. Central banks have reduced rates to historic lows (-ve in case of ECB) to encourage banks to lend to revive the economy, but regulators have strengthened the lending criteria, such that only the “already fortunate” few qualify for loans and the “less fortunate” ones don’t. The riches of the rich are getting richer and the poverty of the poor is becoming poorer.

Thanks for sharing this – I often read, but seldom come across pieces of such high quality and insight.

Best regards

Moiz

PS. I had never seen the facts through the lens provided by your essay – great insight!

An interesting research going back 600 years of the Florence wealthy

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2016/05/19/the-wealthy-in-florence-today-are-the-same-families-as-600-years-ago/